‘We just hired a gentleman of Asian descent who was a food scientist for eight years before he finished law school. I immediately went to offer him a job because it was just unique.’

Gail Sharps Myers, chief legal officer and chief people officer at Denny’s, illustrates today’s corporate drive for better diversity, often as a gateway to diversity of thought – the understanding that a multiplicity of backgrounds will generate a multiplicity of perspectives, acting as an engine for performance, creativity, innovation and, ultimately, more success.

But, as leading general counsel know, diversity is only half the story. Leveraging the collective experience of a diverse workforce is not as simple as hiring different people and alchemizing their perspectives into corporate gold. The secret something, more fundamental than a drive for diversity, is inclusion – creating the environment where diverse people can feel welcome enough to perform at their full potential. And the principles of inclusion are often the same regardless of the type of diversity you are looking to promote.

For Phyllis Harris, general counsel, chief compliance, ethics and government relations officer at the American Red Cross, that means ‘providing an avenue for everyone to thrive in the workplace without thinking about “what is their sex, what is their race, what is their nationality, what is their ethnicity”. In doing so, the way that people thrive is helping them find their value that they will bring to the organization.’

For the legal profession in particular, the stakes for neglecting inclusion are much higher than the risk of losing out to competitors.

‘To truly have an inclusive representative democracy and to have laws that are embraced and supported by all people governed by that democracy, you need to have everyone in the room, which means you have to have lawyers from every ilk, color, division, religion and gender,’ says Carlos Brown, senior vice president, general counsel and chief compliance officer at Dominion Energy.

‘Those that have access, knowledge of and facility with the law tend to be able to create opportunities that benefit themselves and the people they represent. To the degree that African Americans uniquely, but also Asian and Latin Americans and other ethnic minorities, have not had equal access because of discrimination or de facto discrimination with regard to access to law school, or access to the bar or access to certain law firms and certain experiences, it also has a broader societal impact on the way that law is written, the sensitivity issues, and how they impact on the community,’ he explains.

‘Being in the room where it happens – and typically one of the hall passes to get to that room is having access to the law – makes a difference. And for your community and your people, and people who may look and speak and have other similarities to you, to the degree that’s been dominated by one societal cleavage explains why, in many cases, laws have been somewhat insensitive to others.’

The arguments for diversity, equity and inclusion (DE&I) are well known, and their impact on organizational performance has been proven. But it is useful to reiterate them, because the first step in any plan for tackling these issues is to know why you want it.

Step one: understand why

‘Let’s be honest, you’re going to have to ask your people to make changes to their behavior, which they may not like. You’re going to have to ask your leadership to start thinking differently. You have to understand why you want to do this – is it because it aligns with company values, is it because your GC really cares about DE&I, is it just because it’s the right thing to do, or is it the business case?’ says Leila Hock, chief growth officer at Diversity Lab, an incubator for ideas to further diversity and inclusion in the legal profession.

‘Your “why” will drive how you message your work and what that work is, so it’s important to get it right.’

Many organizations were spurred into greater action on race and ethnicity inclusion by the murder of George Floyd. As a wave of protests spread across the US and beyond, conversations about race in took on a new urgency. It became clear that passive opposition to racism was no longer enough – it was time for action. As with many individuals, organizations looked deeper inside than they had before, and found that meaningful change required better understanding of the nuances of systemic prejudice and the complex interplay of privilege and bias, both conscious and unconscious.

Above all else, business has had to become brave enough to listen.

‘Companies are asking questions, people are asking questions. Companies are having candid conversations that I could not have imagined five years ago,’ says Kimberly Banks MacKay, general counsel and corporate secretary of West Pharmaceutical Services.

As corporate advisers, says Banks MacKay, in-house counsel are well placed to facilitate conversations and function as agents of change. But, especially for leaders who are also diverse, there can be a cost.

‘Even though it is critical, and even though it is part of our unique position as lawyers, it doesn’t make it any less uncomfortable. I will say, candidly, as a person of color, you are oftentimes one of a few in the room to help drive these conversations, and it is not always comfortable to have the spotlight on you in that way. But I also recognize the responsibility that comes from that – because sometimes we are the only people in the room to be able to speak to these issues in a very personal way.’

The legal profession is on its own journey towards greater and more inclusive representation of racial and ethnic minority lawyers, both within law firms and corporate legal departments. At the front line of change is the Leadership Council on Legal Diversity (LCLD), an organization of over 400 CLOs and managing partners working towards DE&I in the legal profession. President Robert Grey describes the training the LCLD provides to the next generation of racial and ethnic minority lawyers to foster their success. However, he says, individual preparation is only half of the story. Culture is the other – institutionalizing practices to make them systemic and sustainable.

Don’t change the numbers, change the culture

At the highest levels, the conversation about DE&I might be about strategies, goals, metrics and KPIs. But the workplace, with all its microaggressions, is experienced on a highly personal level – and remembering that in all interactions is the essence of culture.

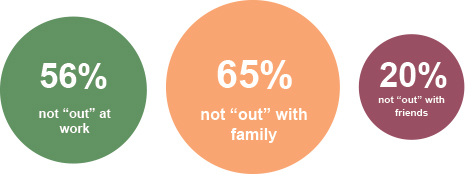

‘Twenty years ago, if you were being invited to a law firm social event, the invitation might say “Please bring your spouse to this event”’, says Rick Sinkfield, chief legal, ethics and compliance officer at Laureate International Universities. ‘I don’t think people meant anything offensive or exclusionary by it, but if you’re in the LGBTQIA+ community, you might be like, well, I don’t have a spouse. I have a partner. And then you wonder, is my partner welcome, or do you have to be heterosexual to attend this event?’

‘Unless that person feels empowered to go to the welcome committee and say, “Hey, maybe we should change that invitation”, then by accident you have sent out a signal. You want these people to stay and be productive and lead your firm, but you’ve kind of given them the cold shoulder,’ he explains.

‘That’s just the little stuff. What about the big stuff? Who gets assignments, who gets to work for which partners, who gets to go on the big trips, who gets to be sent to the Brussels office to learn EU law? It all builds on each other. At every institutional moment, someone has to ask the question: is the way we’re doing things – intentionally or unintentionally – sending a signal that some group isn’t welcome or isn’t on par with the others.’

It comes back to the idea of listening, says Sinkfield: ‘If there are people who are telling you that they don’t feel welcome, you need to listen to them. I think that’s the key to the workplace. Listen to people and try to make the workplace a place where everybody can excel on their merit, and performance.’

Step two: get the right leadership in place

Fundamentally, any good strategy for building inclusion for underrepresented racial and ethnic groups cannot be developed without the input of those groups. Equally, for any kind of cultural change to take root, having the right leadership in place is also essential – and the higher up the executive ladder the better. But whoever the ultimate sponsor is, they must make that commitment personal.

‘You can say that you’re in it to win it, that you have a desire to see a more equitable environment. But what people are motivated by is your conduct – what are you bringing to the table as a leader? Because if you bring your full self to this initiative, with your own commitment, then that will encourage others to do the same,’ says Robert Grey.

Myers has seen the value of this at Denny’s, where the CEO is a diversity champion: ‘As he’s tried to make sure that these issues are addressed throughout the organization, he is very vocal, very upfront, very engaged in all of our employee resource groups. He has empowered his executive team to do what they think is necessary to not only show the new employees and the old employees what our diversity and inclusion engagement is about, but also being totally transparent about the company, its numbers, its activities, and it’s commitment.’

The general counsel is also extremely well placed to spearhead such efforts, as an organizational leader with the ability to drive change, a business adviser with a responsibility to ensure that corporate values, frameworks and actions match, and as a client with the power to drive those values across the supply chain and extend influence beyond the borders of the company.

As a member of the board of directors of the Leadership Council on Legal Diversity, Carlos M. Brown has created a pledge, setting out his DE&I leadership goals at a granular level. They include having a DE&I committee specifically for the law department that provides oversight and engagement of the team’s efforts, while also requiring leaders within his department to submit their own personal diversity plans in which they identify between three and five specific actions that they will own.

Skin in the game

Personal commitment can manifest in many ways, from performance management to personal choices, and leaders who are diverse themselves have the opportunity to be the crest of the waterfall in ways that feel most personally meaningful.

Says Ashley Page, chief compliance officer at Endeavour and former general counsel at Learfield: ‘I have got to a point in my career where I feel strongly that it is my responsibility to bring my authentic self to work every day and set that example for others. I wear my hair in a natural style – I noticed when I joined the team at Learfield IMG College that other Black women in the office started feeling more comfortable wearing their hair in those styles. It is not just about being comfortable in my own skin, it is about a responsibility that I have to lead by example in bringing my authentic self to work and hit difficult conversations head on. Just by having those discussions I set the tone and the example for others around me.’

For all leaders spearheading DE&I efforts, making a personal commitment might involve risk, cautions Robert Grey – but that is part of the personal and organizational stretch required.

‘You’re going to have to risk some personal capital in this effort to show people you’re in it for the long haul. And if you don’t risk anything, nobody else will either,’ he says.

That risk could be reputational, loss of following, loss of face if others are critical of your strategy. But such risk, he says, can be minimized by another of his pillars for a successful strategy – transparency. In this context, transparency could be the support in numbers of others of a similar stature in other organizations being open about their successes, or their attempts.

Step three: be transparent

Myers agrees about the impact that transparency can have, and she has seen it on the ground at Denny’s.

‘You have to have transparency into pay and what you’re doing around your employees. So it’s terribly important, on an annual basis, to do a pay equity study. We do that at Denny’s and have been doing it for a number of years. We report that study to the board and to the executive officers of the company,’ she explains.

‘I think it’s also incredibly important, and it’s kind of new, to have a human capital report. We will be publishing our first in January, and it’s going to have full transparency into our organization, what our numbers look like and what we’re doing to make sure that we either maintain the inclusive environment that we have or that we chase after those areas where we think we have an opportunity.’

For Grey, transparency includes the process of formalizing the leader’s personal commitment by codifying goals in a written form (as with the pledges created by Brown along with roughly half of LCLD members) and displaying those goals to create a sense of accountability.

But when creating a culture of inclusion in in-house legal teams, it might not be obvious where to start. Why? Because many in-house teams suffer from of a lack of data.

Step four: gather data

‘Whereas law firms routinely submit their numbers with regards to the make-up of their teams and leadership, in-house legal departments don’t. There are some organizations that collect that information but, on a large scale, there’s no great way to understand specific gaps in the in-house legal community as a whole,’ says Hock at Diversity Lab.

‘Legal departments are… often made up of and easily attract white women. But when we start to break it down into underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, LGBTQIA+ lawyers and lawyers with disabilities, they have more challenges – and there are certainly challenges around underrepresented racial and ethnic groups,’ she explains.

Hock advises legal departments to find a way to measure where the biggest gaps are, while Valerie Portillo, Diversity Lab’s legal department and law firm integration strategist, also emphazises the importance of simply asking questions, unpicking facts from assumptions:

‘When you start asking questions, you start to uncover things that you were not necessarily aware of. We had a lot of conversations with legal departments that have started asking these questions and they said, “Oh, this partner who we had seen as falling into the faithful lieutenant role is actually the person that is our go-to, so we want to shift credit to that particular person”,’ she explains.

Hock and Portillo stress that the strategic goal should be to establish inclusive structures and practices, which will then attract diverse talent, rather than bluntly targeting underrepresented groups.

‘What we’ve seen in the legal industry is very slow movement of actual increased underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, because often people want to hire and then they don’t change their practices, they don’t make people feel like they belong and then they just go elsewhere,’ says Hock.

‘Look at your current population, make sure you’re not losing your underrepresented lawyers at a higher rate than your overrepresented lawyers. So start with the data and the metrics and go to where that takes you.’

Step five: identify areas of impact

The leader must identify areas of potential impact where change can and will occur, says Grey in another of his pillars for DE&I strategic success. Whatever those areas are, they must be explicitly said and seen.

‘We can’t account for it unless we know what it is, and we can see it, and so we think the idea of measuring ourselves against those pledges and those initiatives we’ve chosen, is also an important tool in the growth and the sustainability of these initiatives.’

We return to the importance of transparency, which Grey sees as an active concept, involving discussion, feedback and iteration.

‘To make [DE&I] scalable, which is a goal of ours, is this idea of socializing these ideas, of crowdsourcing the better practices. And so that’s the stage we’re in now. Now that we are getting people to do these pledges, let’s stay one step ahead of the curve by saying to ourselves: how can we socialize these ideas, how can we elevate the discussion to not what we intend to do but what we are actually doing? Putting those practices in front of people and opening them up for discussion, being critical of them, both internally and externally, will allow us to create the improvement that needs to take place,’ he explains.

Step six: measurement

Grey’s final pillar is measurement, and he is supportive of KPIs for DE&I. But he also is an advocate for peer review in this space.

‘We have operated in silos for a long time. So you ask a major company, “How are you doing?” And they say, “Well, I think I’m doing fine.” “How do you know?” “We’ve got more diversity than we had last year.” Ok, that’s progress,’ he says. But measurement should not stop there.

‘Are you doing the most you can do? Are you operating at the highest level you can? Are you creating a sustainable and systemic approach to the problem you’re trying to solve? What’s the review mechanism for your work? Is it your standard, or is there an industry standard? Is there a peer standard? What are we working with? I think all that has yet to come because we’ve operated in silos so long that we’ve never had a measurement outside of those silos to determine if my initiative is operating at peak efficiency.’

Grey’s ‘socialization’ of the review process seeks to transform it from a purely top-down process to something akin to an agile one, where peer discussions offer feedback and a chance for iteration.

‘I think that this idea of bringing the initiatives to a larger discussion group allows us to be critical, helpful, but, more importantly, to not have everybody trying to invent the same wheel over and over and over again,’ he says.

Building a culture of inclusion is not a quick process because organizations need to challenge themselves. That could take years. But it doesn’t mean that organizations should see that culture change in a different way to other change management processes – like technology transformation, says Grey.

Leadership Counsel on Legal Diversity (LCLD) calls for leading in-house counsel to make a personal pledge to move diversity to the front burner of their organization. Among those having taken this pledge is Carlos M. Brown, senior vice president, general counsel and chief compliance officer at Dominion Energy. The pledge offers an example of how general counsel can commit to D&I.

I, Carlos M. Brown, personally commit to the following:

- I will champion diversity and inclusion by leading by example. My current leadership team consist of six individuals, three of whom are women and two of whom are African American. I will endeavor to maintain at least 50 plus percent diverse representation on my leadership team, including at least 25 percent racial and ethnic representation.

- I commit that my succession plan and the succession plans of each of my direct reports and each of their direct reports will maintain at least 50 percent diverse representation, including at least 25 percent racial and ethnic representation.

- I commit that 50 plus percent of the new hires in our organization will be diverse, which is consistent with our corporate goal and I will actively participate in the recruitment of a talent pool that will ensure that this goal is successful. I will own this goal.

- I commit that our law department will spend at least 30% of our outside spend with diverse firms or diverse matter responsible attorneys at majority firms and vendors.

- I commit to identify 3-5 associates at our principle outside law firms and will personally meet with them at least twice per year to provide coaching and mentoring and will insist on their substantial participation in our matters. Further, I will formally inquire with firm leadership twice annually as to their development and prospects for promotion.

- I will commit to make myself available to diverse talent at every level of Dominion Energy and identify 3-5 individuals that I can mentor and sponsor for inclusion on executive leadership succession plans.

- I will commit to an annual in person meeting with our outside law firms to review lawyer staffing on our matters. We will establish a goal that 35% of our work be led by or have a billing or relationship responsible partner that is a woman or a person of color.

- We will support our teams continued participation in Leadership Council on Legal Diversity, the National Bar Association, Women of Color, other minority bar associations and local chapters. We will support the organizations financially and with our attendance at programming in order to support the work of these critical organizations and provide development opportunities for our diverse attorneys and their allies.

- We will continue to participate in the LCLD 1L program at the level of at least 3 interns per year. We will encourage our principle firms to convert 1L offers into 2L offers and ultimately into permanent offers. We will commit internal resources to supporting these interns throughout their law school careers and after.

- I commit to champion social justice and diversity and inclusion at Dominion Energy, in our industry and in all other spheres of influence that I may have. I will not just take up the seat at the table that has been set aside for diversity, African Americans or other people of color, I will use my voice, I will say something, I will lead.

‘“We’re going to be the best at technology than any other company”, and when you decide you want to do that, guess what? You just unleash all of the talent and authority and power, and you drive it. You start saying “I want know what we’re doing about this.” If you hold people to that same standard on diversity, then we will drive a more productive effort at making it happen.’

He adds: ‘Part of the storyline is if you apply the principles of success to diversity that you apply to other areas that you consider a challenge, you will be successful, because we know our own track record at doing these things.’

We’ve seen six steps towards a framework for inclusion, comprising understanding, leadership, transparency, data gathering, targeted potential impact areas, and measurement. Next comes the task of populating that framework with the meat of a DE&I strategy – the initiatives.

A good initiative should embed structure into processes and talent systems. In an echo of Robert Grey’s pillars for a DE&I strategy, Leila Hock at Diversity Lab believes that a good initiative should include structure, accountability, transparency and collaboration.

Cultural competence

Improving D&I through recruitment requires some degree of cultural competence, says Grey: ‘You can’t just say, “I want people from the Middle East” if you don’t know anything about people from the Middle East in your organization. Or, “I love African Americans, I’d like to have more of them”. If you don’t know anything about their plight and about the obstacles they’ve had to deal with, then how are you in your organization going to develop those individuals in a meaningful way?’

First of all, it’s essential to go where talent is, and organizations can expand the target talent pool instantly by going to the right colleges and law schools and seeking out the best candidates. But exploding structural inequalities that impact the talent pipeline takes investment in potential talent before the point that they are ready to enter the workplace.

Mentoring can be effective, says Brown. He recalls his own time as a law student preparing for the LSAT exam, when he happened to bump into Justice S. Bernard Goodwyn – the only African American lawyer he knew – in the law library. Justice Goodwyn advised him of the availability of a grant to partially fund LSAT preparation classes, something he was entirely unaware of.

‘My score increased by 20 points between my initial practice test and the actual LSAT. That LSAT score allowed me to get into Harvard, UVA, Georgetown, and a number of other very prestigious law schools, and so made me a candidate for significant scholarships. But for the fact that the one black lawyer I knew, Bernard Goodwyn, saw me in the library that day, I never would have known of the material difference that that prep class would make in my career and life. I likely would not have prepared, likely would have underperformed, and likely would not be here talking to you today,’ says Brown.

The intersectionality of diversity is an important factor, with economic disenfranchisement and other factors often overlapping with racially and ethnically diverse candidates. Brown is vocal about the need for underrepresented racial and ethnic minority lawyers to receive support throughout the entire process of qualification, whether applying to law school, achieving at law school, navigating the world of recruitment, and then getting the market exposure and visibility to succeed in their careers. Otherwise, he says, the structural obstacles faced by would-be lawyers without the experience or exposure to the law of others, without knowledge of the system gleaned from family or friends, will stymie even the brightest sparks. Internships and sponsorship for diverse student candidates can be effective.

When it comes to drafting job postings, it is important to not accidentally screen out diverse candidates by being needlessly narrow in the requirements – for example industry experience or length of service – and to focus instead on qualities, such as leadership, initiative, versatility, creativity and energy. Vacant roles should be advertised outside the traditional channels, in places that encourage a diverse slate, such as colleges with a historical representation of the groups you are looking for, affinity group bar associations, and websites of relevant organizations.

When the résumés come in, it’s important that the selection process and interview panel are staffed by a hiring team and interview panel reflecting different races and ethnicities, as well as genders, and even different parts of the business. The decision cannot be influenced by one perspective if all candidates are to have a fair chance.

Inevitably, DE&I is a chicken and egg story – if you build an inclusive culture, diverse people will come, but is it possible to create – and maintain – that truly inclusive culture without the input of diverse people in the first place?

This process is a journey along a continuum – and it’s crucial to meet people where they are, which will depend on where they’ve come from along that journey, says Grey.

Perhaps key to beginning that journey of inclusion is to confront unconscious biases and turn a room of people with unacknowledged prejudices into a room of allies.

But to uncover those biases, you need training. Lots of it, potentially.

‘Training and exploration of unconscious biases, not just in a two-hour or three-hour seminar, but in an ongoing way that will have stickiness within an organization is key, because that’s where you have to start. You have to change the mindset. Once you change the mindset or open up the mindset, then the real work can begin,’ says Myers.

Mentoring, sponsorship and allyship

Mentoring and sponsorship are important tools in the inclusion kit, to help racial and ethnic minority associates build on their strengths, navigate the cultural landscape of the company, and benefit from the various experiences of those who have succeeded.

‘That does not necessarily mean a mentor of the same race or ethnicity. I can say from my own career that some of my best mentors were white men, because they were very interested in understanding my challenges – and I was not shy in telling them some of the obstacles I was facing as I was practicing law,’ says Harris.

But just having a mentoring or sponsorship initiative in place does not mean that beneficiaries are effectively prepared for success if that initiative is not properly devised and implemented. This point speaks to the importance of Diversity Lab’s mantra of structure, accountability, transparency and collaboration.

‘An underdeveloped mentor or sponsorship program just says, “Valerie, meet your new mentor, Leila. Develop a relationship.” And that’s where actually a lot of mentoring programs stop,’ says Hock.

‘There’s no structure to how the relationship should go, there’s no accountability to make sure that the mentor and/or the sponsor actually checks in with the protégé or mentee, there’s no transparency in really understanding how that relationship is going, and there’s no collaboration amongst the mentors or sponsors or protégés.’

Phyllis Harris adds that mentorship by itself is not enough – there must also be structures in place to make sure that diverse colleagues are actually getting an equitable bite of the pie.

‘The organization needs to ensure that these individuals are getting the assignments. That allows for visibility. It’s not enough to invite people to the party, you’ve got to go across the room and ask them to dance. You ask them to dance in the legal profession when you ensure that people are getting good assignments and they are getting good, constructive feedback. The worst thing you can do is bring people into the organization and set them up to fail by not sharing with them how they can improve, as well as sharing with others when they do really good work,’ she says.

Some cross-over between mentorship, sponsorship and allyship may occur, but fundamental is advocacy, which points back to the strategic pillars of personal commitment and putting skin in the game when working to increase inclusion of racial and ethnic minority lawyers in-house.

Hock describes ‘Ally Action Pledge’ initiative, which challenges law firm partners (though she stresses it could work for senior corporate counsel) to sign a pledge, committing, for example, to advocating on behalf of a lawyer from an underrepresented group, introducing them to high profile people, taking an active role in their work assignments, and making sure they get the exposure, visibility and experience that they need.

‘It’s important to make sure we involve underrepresented racial and ethnic lawyers in these initiatives and strategies and initiatives, but they can’t be doing the work. We have to get allies involved,’ she says.

‘An inclusive workplace is better for everyone, it’s not about stealing their role or opportunities, it really is about inclusion for everyone.’

Succession planning

At Dominion Energy, Brown has worked to ensure that diverse counsel don’t hit a glass ceiling within his in-house team by embedding inclusion into departmental succession planning. All succession plans, including those of his deputies and managing counsel, must be 50% diverse before he signs off on them. This, he argues, bakes in support for those diverse lawyers all the way up the corporate ladder.

‘If that means that you have to identify a candidate who you might say is not ready now, then that’s fine, but by putting them on that list you are committing as a leader reporting to me that you are going to undertake the steps you need to get that person ready to be a candidate to compete for your job. So that it no longer is the case that when an opportunity arises and we go to the list we say, “Gosh, the reason the list is all white males is because there just was no one ready”,’ says Brown.

‘That circumstance is true for everyone until someone invests in them to get them ready. For years the excuse has been used that we don’t have any “ready-now” candidates. But the candidates that are ready now are ones who someone identified three, five, seven, ten years ago and said “Hey, we’re going to line this person up with the experiences and the exposure so that they can one day be a deputy GC or a GC in this company.” That same type of deliberate intentionality should happen for women and minority candidates, and so that’s something that we’ve mandated.’

Initiatives: the supply chain

A similar long-term intentionality can be applied to peer pressure along the supply chain – an outlet where general counsel keen to promote DE&I in the wider legal profession have much agency. Corporate counsel can be more specific than demanding racial and ethnic minority lawyers on their work – they can demand that they be supported, developed and well enough exposed to become the experts that clients demand.

Says Grey: ‘I don’t want you to put a minority lawyer or an ethnic minority lawyer on a case because they are ethnic minority. That doesn’t help me. What I want to know is who’s in that practice area whose job it is to do that kind of work and are they doing my work? That is turning the aperture to be more focused.’

Diversity Lab’s Hock acknowledges the difficulty for in-house teams to establish these new working relationships with longstanding outside counsel. In a bid to overcome this, Diversity Lab has an initiative called the ‘Diversity Dividends Collective’, which tracks demographic data of outside counsel teams, revealing to in-house teams who is receiving financial or expansion credit for leading their matters. The organization hopes that this tool will help legal teams work in partnership with their law firms to achieve better results, rather than point the finger.

‘Instead of saying, “You need to do better”, it’s saying “Look, these are your gaps, we understand them, how can we help you?”’, says Hock. ‘It’s recognizing that law firms play a role, and it is not enough to just incentivize them or say “Give us your data and we’re going to make decisions based on that”. There needs to be a consistent dialogue between legal teams and their law firms.’

‘We’ll only see true progress as a legal industry if we see ourselves as just that, a legal profession, not us and them, a legal profession working together hopefully to change the entire profession and the systems of the entire profession.’

Dominion Energy has its own tracking system for outside counsel, which encourages billable credit to be given to diverse lawyers by tying part of the legal department’s bonus program to a point system predicated on number of matters given to, or number of hours spent by, diverse outside lawyers.

‘We’ve been doing this now for about four or five years and we’ve grown our diverse spend. About 20% of our legal spend now can be credited to minority, veteran-owned, women-owned firms, or diverse lawyers at majority firms,’ says Brown.

Putting the pieces together

Better collaboration is both the reason for diversity, equity and inclusion, and the solution at the heart of strategies to achieve it. It means reaching out, accessing the know-how already out there, gathering best practice, and working to move the conversation on, and on again.

‘Our suggestion is to be bold, and you can’t be bold unless you know that there’s something better than what you’re doing out there,’ says Grey.

‘Is it uncomfortable? I think it’s a little uncomfortable, because nobody’s been doing it in the past. So, we’ve got to get to a different level of comfortable about how we work with this area. I think we come from not being comfortable at all, to now we think we’re comfortable because the status quo in a sense affords us some protection against doing more. And I think we’ve got to guard against that and say the status quo is not good enough.’

First, we should make mindful decisions about who we hire and resist the urge to favor people who look like us, went to the same schools as us or grew up in the same towns as us. Then, once you have a diverse legal team, be mindful that everyone’s experiences are different, and just because something has worked well for you, does not mean it will work well for me. Unsolicited commentary about the way one person handled a situation could be received differently than may have been intended so we should be aware of the impact of our words. Allow lawyers to develop their own styles and manage their projects as they see fit as long as the common goal to fulfill a client’s needs is being met.

First, we should make mindful decisions about who we hire and resist the urge to favor people who look like us, went to the same schools as us or grew up in the same towns as us. Then, once you have a diverse legal team, be mindful that everyone’s experiences are different, and just because something has worked well for you, does not mean it will work well for me. Unsolicited commentary about the way one person handled a situation could be received differently than may have been intended so we should be aware of the impact of our words. Allow lawyers to develop their own styles and manage their projects as they see fit as long as the common goal to fulfill a client’s needs is being met.![]()

When I joined Sodexo 11 years ago, diversity and inclusion was part of the DNA of the company even then, but not in the same way that we work now. Ten years ago, these topics weren’t part of the board of directors or the leaders of the company. Nowadays, I think it’s not acceptable if a company doesn’t take the time to discuss these topics at board level. It’s not about one specific sector or business – the market in Peru needs to talk about diversity and inclusion.

When I joined Sodexo 11 years ago, diversity and inclusion was part of the DNA of the company even then, but not in the same way that we work now. Ten years ago, these topics weren’t part of the board of directors or the leaders of the company. Nowadays, I think it’s not acceptable if a company doesn’t take the time to discuss these topics at board level. It’s not about one specific sector or business – the market in Peru needs to talk about diversity and inclusion.