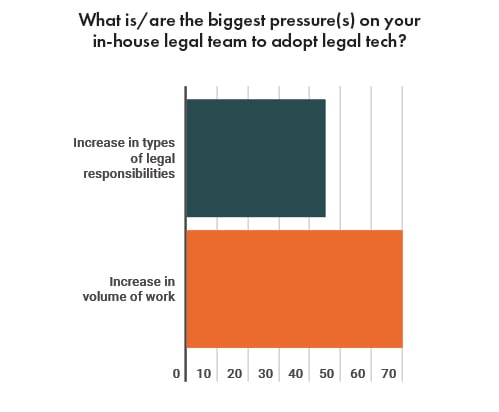

Invention is the child of necessity, to spoonerise a common maxim. Either way we read the maxim, it’s worth taking the time to look at the current state of play for in-house counsel – the necessities they currently face and inventions, both social and technological, which have been developed – and may be developed – in response to these new pressures on in-house counsel. After speaking with GCs around the globe, a picture emerges that can be drawn in quick strokes: the volume and type of work have steadily increased, and only accelerated through Covid. GCs, generally, have been left to their own devices by corporate to find solutions to these pressures. However, the legal tech market is, as evidenced in our current global survey, complex, with a multitude of tools available to in-house counsel. How can GCs based in Africa safely ford this river?

As we have seen time and again after speaking with GCs and in-house counsel around the world, the interconnected nature of modern-day life and the systematisation of corporate structures means that the form of in-house counsel is recapitulated in different sectors, across different legal regimes, and different cultures. However, that recapitulation of roles and duties nevertheless reflects the specific socio-politico-cultural aspects of wherever the GC is operating. Additionally, while the form may be similar, the content often differs considerably. After speaking with a broad range of GCs in Africa, it is clear that while there are broad differences, there remain similarities shared between them, as well as similarities with all GCs in the pressures they face and the solutions they have attempted to implement to decrease the pressures that all GCs can relate to, including an increased workload, complexity, and diversity of matters.

Of particular interest within Africa’s growing legal tech scene is how quickly it has grown – and how it is not entirely limited to private practices or in-house legal teams. Rather, many entrepreneurs have attempted to use legal tech to make it easier for the non-lawyer to receive up-to-date information on their legal rights or obligations, be it securing legal counsel or setting up a company. But our focus will be primarily on the specific recent circumstances that affected how all lawyers operated, and how lawyers are trying to use new developments in legal tech to stem the tide.

Based in Nigeria, Tochukwu Okezie is chief legal officer at Interswitch Group, an Africa-focused digital payment and commerce company, active since 2002. Tochukwu explains in detail the developments in in-house lawyer responsibilities, saying: ‘Increasingly, GCs are relied upon by companies to provide advisory beyond their core legal issues. Commercial teams are leaning more on in-house lawyers to provide robust advice that cuts across core legal issues to also include advisory work on commercial positions to be taken by the company. In-house lawyers are expected to understand transactions in their entirety and provide wholistic advice that addresses not just legal issues but other aspects of the transaction’.

Tochukwu’s own experience is not unique. In fact, as detailed in our article on legal tech in the Middle East and the global research report, GCs globally are experiencing an increase in duties and responsibilities, exacerbated by Covid, while seeing little to no increase in funding to plug the gap. The corporate side’s necessity increases the pressure to do more types of work, scale up, increase efficiencies, and do more with less, forcing GCs to invent their way out or collapse under the pressure, just as many other workers in other sectors.

Omisakin Ayobami, legal counsel at Interswitch, provides another point of view regarding the pressures that face legal teams, saying: ‘the pandemic hastened the adoption of tech tools as more in-house counsel teams now work remotely.’

Tochukwu elaborates on the extension of these responsibilities, noting: ‘Some of these “other aspects” include the ability to assess the overall risks of certain corporate endeavors. This ability to assess certain risks points means that today, the in-house lawyer is also considered a risk manager by corporate. In-house lawyers are typically expected to manage legal risks; however, this expectation now extends to general operational risk management as part of their day-to-day assessments.’

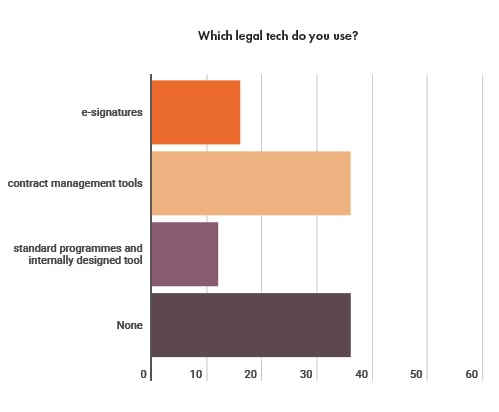

Ayobami concurs on the extension of legal duties in in-house teams, but also noting how many African corporations have begun taking the necessary steps to alleviate the strain on legal teams, stating: ‘There have been discussions around the automation of legal processes for in-house counsel teams and the adoption of relevant technology tools for contract management, IP rights protection and litigation portfolio management.’

This new added responsibility of risk management is, however, a skill set that many GCs are not equipped with and requires picking up these skills on the fly. Thankfully, GCs we spoke with generally believe they are up to the task; however, even if GCs can quickly pick up these new skills, where does it end? Risk management was, for many in-house counsel, not on the job description. And whatever new role corporate asks from GCs will similarly not have been listed as a core duty.

Additionally, it’s important to address the acceleration of new duties laid on in-house counsel by corporate due to Covid. The economic and social shocks continue to reverberate back and forth between different subsystems, throwing out of alignment entire industries that had been held in a tenuous equilibrium. And for GCs, this means quickly responding to several large-scale corporate problems, often with little space to rest in between each problem.

Tochukwu explains: ‘The global pandemic offered up different scenarios that underscored the in-house lawyer as an operational risk manager. From dealing with new employees who had been issued contracts to resume employment just before the quarantine orders and the associated hiring uncertainty crept in, to dealing with other pandemic staff-related issues such as mandatory physical meetings or company seminars and events. The risk of staff getting infected at such events, the possible legal action that could arise, and also the operational risks of exposing other staff members to the virus. These are just a few of the general issues GCs faced. In short, the global pandemic accelerated the expansion of GCs and in-house lawyers’ responsibilities and the expectations have continued to grow post the global pandemic.’

Omisakin Ayobami

Ayobami is a legal practitioner in Nigeria and practices in the nation’s commercial capital, Lagos.

He works as a legal counsel at Interswitch Group, an Africa-focused integrated digital payments and commerce company. In Ayobami’s current role, he drafts and reviews contracts; works with external counsel to develop case strategies for disputes; and is part of the team that develops and manages the in-house contract management framework.

Though seemingly disparate, Ayobami typically looks to bring his dispute resolution experience into transactional work in his role as in-house counsel and this helps him provide a robust approach to contract drafting, pre-litigation and dispute avoidance advisory.

In addition to his experience in the financial technology and dispute resolution practice areas, Ayobami, in his previous roles, has advised on local and cross border mergers and acquisitions deals, helped structure key joint venture deals in the real estate sector, advised multinationals on the local labour law landscape and provided legal advisory on data privacy and protection.

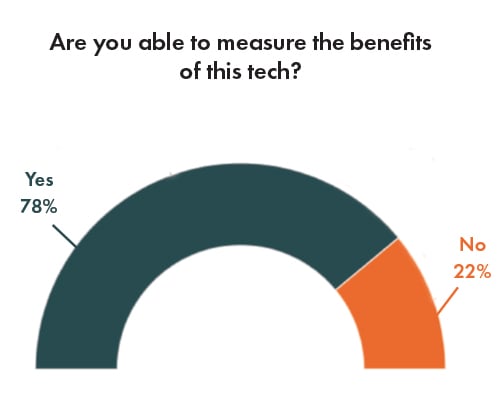

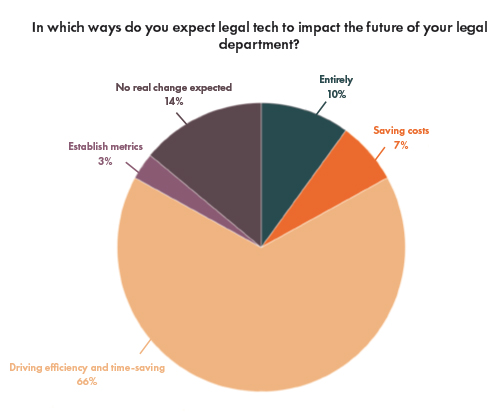

Thankfully, legal tech was there during the crisis to help legal teams in Africa. Tochukwu notes: ‘Technology has already helped in-house legal departments improve legal efficiency. For example, having a dashboard that shows all pending requests logged with legal enables the legal operations lead to monitor workloads across the team and ensure even distribution of tasks. With technology, we are currently able to track time spent dealing with tasks and also track the volume of work. The right tool would guide the GC on not just task-allocation but also resourcing decisions.’

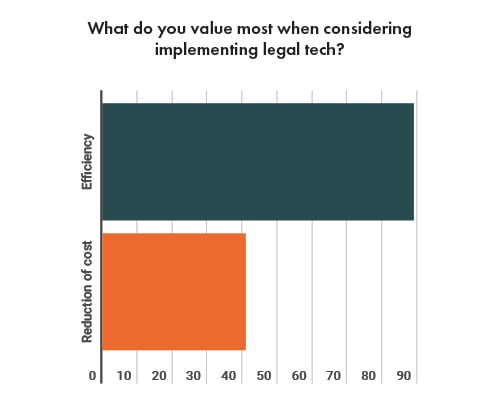

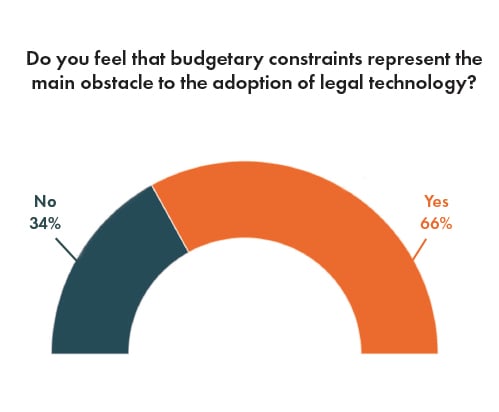

Additionally, many forms of legal tech that have been implemented were not especially onerous on companies. ‘Deploying technology into the legal department is not necessarily an expensive venture. Sometimes the company has some existing enterprise solution licenses which legal departments can leverage. This would entail the GC working with the tech team or legal operations team in assessing the existing solutions already deployed in the company’s environment or accessible to the company by virtue of its existing licenses,’ says Tochukwu.

However, costs cannot always be measured in currency. As Ayobami notes: ‘Efficiency, training sessions and added costs should not be viewed exclusively. Yes, it has increased the cost of the in-house legal team, especially since it required a lot of unwanted training for in-house counsel, but these are sacrifices required for achieving greater efficiency. Now we can say the benefits are immense.’

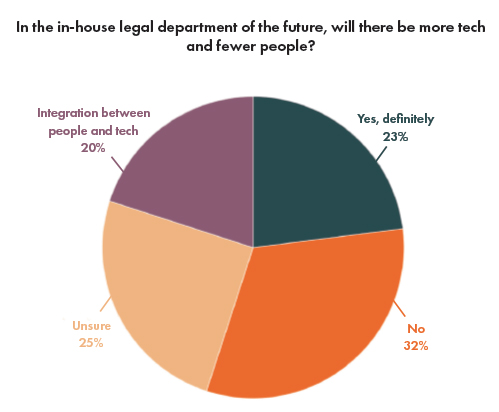

The in-house legal departments of the future

In response to this acceleration of responsibilities taken on by in-house counsel, many GCs we spoke with are thinking towards the future, and what material changes in the structure of the workplace can be introduced to alleviate the increased workload. Some changes are more noticeable than others, and affect in-house counsel differently, depending on their duties. Ayobami’s personal experience involved the noticeable increase in modes of communication both within teams and with external partners, stating: ‘The most obvious changes in recent times are the increased reliance on instant messaging tools for seamless communication and investment in home office set-up for in-house counsel.’

However, while there may be technological developments that facilitate communication both within and outside in-house legal teams, there remains the major structural hurdle that, in the eyes of many GCs we spoke with, corporate has, and will likely be for the foreseeable future, more stingy with the purse strings when doling out funding to in-house legal teams than other teams. But GCs are resourceful, and are looking to the future for methods to take some pressure off their backs.

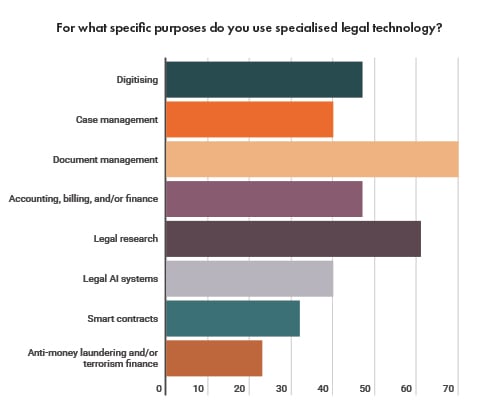

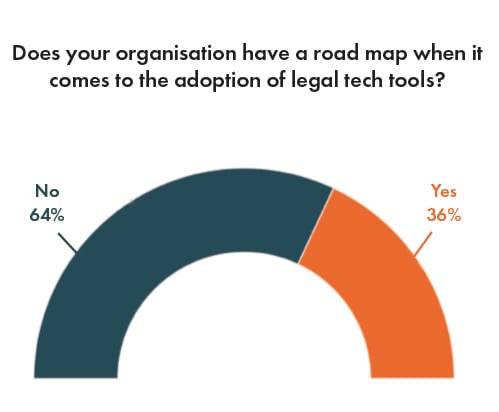

Tochukwu sets out one vision of the future, saying, ‘in-house legal departments of the future would be more technologically driven. Repetitive processes and basic legal tasks would be automated. Legal departments would lean more on tech solutions that can address the entire gamut of the legal department’s operations – from contract lifecycle tools, dispute and case management tools, intellectual property management, and other departmental-specific functions.’ Tochukwu’s vision isn’t unique – many GCs surveyed express similar desires to see automation of mundane, rote tasks that are done in bulk, which would alleviate much of the pressure and allow GCs to focus on the types of complex work that interest them.

Thankfully, when considering the current structure of most in-house legal teams, we can see the beginnings of the end – that is, legal tech and technological developments in general have already changed much of the normal functioning of in-house teams and GCs; however, in many cases, these changes are still in the early stages, and don’t have the full corporate buy-in required to take off the extra weight.

Tochukwu elaborates on this, saying, ‘currently, a number of legal departments have tech tools to manage different legal functions. Contract management solutions, automated notifications to manage periodic reminders that can cut across court hearing dates, expiration dates of important documents, and so on. For legal departments that manage company secretariat services, they would also consider having a Board Solution to manage company secretarial activities.’

Ayobami foresees different developments, noting, ‘I think the legal industry will see more investment in technology to promote automation of key processes, chief of which are request initiation from business departments, contract review, execution, management and productivity.’

Without immediate access to these tools and technology commonly in place throughout the globe, most in-house teams would be unable to maintain their normal workload, effectively reverting GCs to their pre-internet counterparts. Or, in some cases, a power outage would render in-house legal teams entirely ineffective until power is restored.

However, when looking towards the future rather than dwelling on the past (or the fears of a power outage), Tochukwu provides further thoughts on what he expects legal departments of the future to look like, saying, ‘eventually, I think, legal departments would seek robust solutions that can encompass all its legal operations in a single solution. For example, a single tech solution with different modules that can handle contract management lifecycle, litigation and dispute management lifecycle, intellectual property and other legal functions.’

Ayobami, however, believes that future in-house legal teams will develop more on the personnel side, saying, ‘more than ever, in-house counsel teams have seen the need for building expertise at various areas of law in a bid to increase efficiency. Whilst more specialist lawyers will be hired to advise the company on key areas of its business with lesser dependence on external counsel, the recruitment of lawyers with expertise in multiple areas of law would be the game changer for in-house counsel teams.’

Tochukwu brings up a simple solution to a major issue that numerous GCs have brought up during interviews and in surveys: current legal tech often remains niche, siloed from other systems, and often not cross-compatible. Therefore, even if new legal tech software currently serves an important role that alleviates the increased time and energy required of in-house teams, or even may be highly effective in solving specific problems through automation, the multiple types of software cannot interface with one another. Unification and consolidation of legal tech into a series of core modules that can be independently purchased under an overarching framework would solve these problems of cross-compatibility overnight.

Tochukwu continues, saying, ‘imagine scalable and adaptable solutions that can, for instance, take on new legal functions as they arise, deepen the existing legal functions, embed imminent new tech, for example, artificial intelligence and machine learning into its various modules (which, among other functions would assist in assessing not just legal but operational risks) with a focus of improving legal efficiency. Rather than having multiple incompatible tools, legal departments would be better served by a legal department management solution that can be utilised across a wide array of legal functions while also remaining adaptable as the corporate expectations of legal departments functions continue to increase.’

Contrasted to Tochukwu, Ayobami’s thoughts about the future help clarify the legal tech/legal personnel relationship, noting that in response to the increased presence of legal tech, ‘I think the legal operations and data analytics roles will grow into prominence in years to come as more in-house teams in Nigeria see the need for both. Whilst generalist lawyers may meet these operational needs currently, the role would require specialists in the coming years, either non-lawyers who have a good grasp of legal operations or lawyers who have developed core experience in operations. This also applies to data analytics and data science roles as companies CEOs and GCs understand the invaluable benefits that could be derived from the data.’

While there are many forms of tech that quickly embraced cross-compatibility and modularity (think of, for example, corporate software released by Microsoft and Apple), legal tech still remains in its early stages, in what feels to many GCs as lagging behind technological developments that have long been taken for granted elsewhere.

Much of in-house work still is paper-based, which naturally produces an additional step that eats up the time and energy of in-house legal teams. Tochukwu provides some personal experience on this, saying, ‘to bridge the tech gaps in legal operations, it would not be uncommon for GCs to engage non-lawyers in the legal department to manage the digitising of legal operations, for example, or manage the tech, provide advice on implementations and modifications of the tech, extract report friendly data for the GC’s use, and so on.’

On this point, as GCs are well-aware, in-house legal teams are not limited to GCs, but include a large number of staff who are similarly under pressure from corporate to deal with ever-increasing duties. The role of GCs may differ from the roles of other members of their teams, but nevertheless, increases in efficiency due to adopting legal tech will similarly alleviate the strain put on these teams, allowing them to provide better service and with less workload. This is something that the corporate side should take seriously. A happy in-house team makes for a better in-house team.

Legal tech start-ups disrupting the African market

While it’s obvious that many in-house legal teams will rely on software developed by international corporates, it’s not surprising that home-grown legal tech in Africa has expanded rapidly, with many start-ups, regional powerhouses, and other businesses developing software aimed at African in-house legal teams. This is borne out in the available data, with Global Legal Tech Report’s 2020 Africa edition setting out a number of interesting results. Take, for example, the fact that in 2020, Africa saw 53% of the youngest tech legal company founders under thirty, far more so than when compared to Asia, Australia, and New Zealand, where legal tech founders are generally above 30 years old.

Produced through a collaboration between African and international legal tech groups, the report identified emerging legal tech hotspots in Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Uganda, and South Africa, with many legal tech firms seeking to expand into other local markets, and eventually move globally. For example, the report noted that 75% of respondents were seeking to move into West African markets, followed closely by Eastern African markets (67%), and Southern African markets (42%).

Notably, the survey discovered that the oldest legal tech company they could identify had been founded in 2005, making the African legal tech sector one of the youngest globally, and indicating that it will be undergoing major developments in the future. Part of these relatively early stages in developments in African legal tech involve securing funding, with the report noting only a third of respondents successfully raised the necessary capital to continue operating.

However, even in this highly competitive market space, it’s clear that African lawyers are in need of legal tech that understands their needs. That’s why entire related industries dedicated to evaluating legal tech have exploded into the market. Take, for example, The Lawyers Hub, a legal tech organisation headquartered in Kenya that focuses on legal tech in the global South. It runs Africa Law Tech, a series of global summits and festivals dedicated to highlighting the best in African law tech in order to facilitate networking between African legal tech start-ups with tech policy leaders, governments, financers, and industry experts.

African legal tech start-ups cover a broad range of issues and potential clients, ranging from private practice and in-house counsel to non-lawyers. The breadth of legal tech is impressive for how many areas African legal tech has expanded into in recent years. Nigeria, for example, saw in 2015 the development of LawPàdí, which aims to educate Nigerians not well-versed in law on a whole host of legal issues, as well as how to connect to legal professionals.

South African-based JusDraft focuses on legal practice management systems, specifically designed to automate the drafting of legal documents or court forms without an attorney. South Africa also saw the reveal of Citizen Justice Network in 2015. Developed by the journalism department at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, it brings together paralegals and community members to educate the public on social justice issues and legal rights.

There’s Crimesynch in Sierra Leone, a case management system which focuses on improving legal justice by linking prosecutions services, police and prison services together. Algeria’s Legal Doctrine is an app designed for mobile and tablet that allows access to a legal database of Algeria’s legislation, court decisions, and regulations.

And last, but certainly not least, are the start-ups founded by established lawyers from outside Africa, such as Afriwise. Founded by CEO Steven De Backer in 2017 and based in Brussels, Afriwise is designed to easily supply regulatory and risk-related information regarding 16 countries in Africa, and four countries planned in the near future. Afriwise seems to be aimed at international corporates interested in operating in Africa by supplying

up-to-the-minute details about African legislation, how to set up businesses, employment contract information, participating in tenders, and securing licenses, and so on.

Ayobami notes how these developments on the corporate side of businesses will inevitably influence hiring decisions on in-house legal teams, noting, ‘this is key, not only for talent recruitment but also for talent management and talent retention. There is a need for more defined roles that carry a strong sense of importance. However, agile models must be adopted to allow role modification as team members grow and develop other interests. It may take time but over time, a balance will be achieved between business needs and individual interests.’

While this current approach of relying on other members of in-house legal teams to perform much of the drudgery may be currently serviceable, it nevertheless can influence the hiring process in ways that may not be made explicit. Tochukwu says, ‘this current approach of pulling talent to deal with digitising documentation may be a viable approach to handling digitisation of the legal department; however, the assumption is that a GC who would typically have a limited recruitment budget would tilt towards employing a lawyer with the same tech skill set as a non-lawyer.’

On this point, we see the same general trend in modern-day attempts at automation: oftentimes, what is presented as a completely automated process requires a great deal of unsatisfying, repetitive manual labour hidden behind the scenes, whether it is scores of people directing content moderation on Facebook or Twitter or all the young in-house lawyers filling out forms in a back room. Additionally, those in-house lawyers face the issue of, as mentioned previously, quickly adapting to whatever new duties corporate can devise.

Thinking of the not-to-distant future, these important soft skills present on many modern-day CVs are becoming even more relevant. Even if automation of these manual tasks is fully achieved and the pressure finally alleviated, the ability to cover novel tasks will likely influence the hiring process in the future to an accelerated degree. Tochukwu notes, ‘beyond reliance on tech solutions, or employing lawyers with diverse legal background, it is predictable that lawyers with tech background or experiences working with robust legal tech solutions would become essentials for legal departments.’

And it isn’t just the ability to adapt to new legal tech, but also communicate with other teams in a corporate environment: ‘In the future, the communication gap that legal departments face in conveying user requirements to tech implementers (either in-house or outsourced) detailing how legal departments expect their tech to function would be bridged by these categories of digital native lawyers. The diverse legal experience of the future would not only entail experiences across various aspects of the law but would also include an experienced tech background. Legal resourcing would generally consider legal officers that are knowledgeable and can use these technologies comfortably. A premium would be placed on lawyers who can offer both core legal services and contribute to enhancing legal operational tools.’

Of course, with all these developments in legal tech to automate processes, this does not let lawyers off the hook. Instead, with every new solution comes a swathe of new puzzles, problems, and issues for GCs. Tochukwu rightfully points out that as new legal tech is put in place, ‘lawyers would be expected to continuously review the legal processes and advice on deployment of solutions, automations, tools to track legal requests as they come in, track the response time, track the details of the requester and closure of the request and continuously research and identify alternate solutions that can meet legal department’s ever-growing user requirements.’ While automation may be the most anticipated and desired solution to increasing demands on in-house legal teams by taking of the pressure of many administrative duties, it is in no way a silver bullet.

The modern-day structure of the legal team

Tochukwu elaborates on the current environment and structure of in-house legal teams, stating, ‘it is always important to assist legal teams connect their day-to-day tasks with the larger purpose of the organisation. This creates some form of meaning, purpose and self fulfilment for team members. One approach I have adopted is with regards to management reporting. Management reporting now goes beyond regulatory or litigation reporting as companies increasingly want to understand how legal activities feed into the company’s goals. Working with our legal officers to craft the management reporting, which captures legal activities in a language that resonates with the strategic objectives of the company, serves as a continuous reminder to the legal officers of the larger corporate strategic picture.’

Tochukwu continues: ‘In addition to building a sense of purpose by connecting the dots for legal teams, it is important for GCs to create departmental structures that show a clear career growth trajectory for members of the team. GCs may consider structures that speak to areas of responsibility, supervisory functions over younger lawyers and clear-cut designations. It is important for lawyers to understand their growth path as this serves as an effective motivator.’

Consider, for a moment, how the legal landscape has drastically changed over the past decades as legal tech and other forms of technology have become more readily available. Before the internet and emails or the general digitalisation of documentation, work was limited by the speed of typewriters, phone calls, or fax machines – and before then, the speed of mail carriers. The structure of the modern-day office bears little resemblance to, say, an episode of Mad Man, and with increased efficiencies includes the speed of communication.

Ayobami elaborates on this point, saying, ‘many teams now rely on technology and those who are yet to adopt the same are planning to do so. Even CEOs are becoming increasingly interested in the automation and efficiency of legal processes so it is expected that GCs enjoy more support as they rely more on technology. We now rely heavily on technology to ease our contract management process and the key areas where technology has proven useful.’

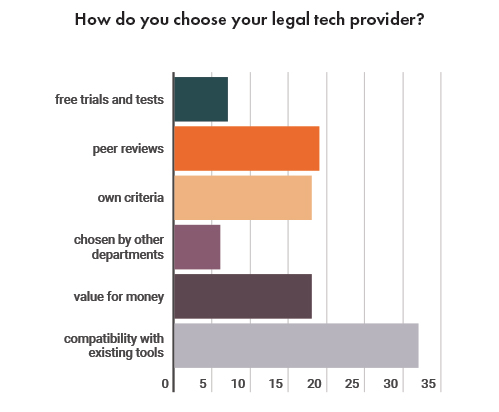

Okezie Tochukwu explains what goes into his decision-making process when deciding on which appropriate tech solutions to adopt

‘Some of the factors I consider in deciding appropriate tech solution are:

A. Department’s user requirements: first step is to highlight all the problems the department intends the solution to address. Once this is clear, each proposed solution is reviewed to identify which solution best addresses all the user requirements. Additional features not contained in the user requirements may come in handy where such features are relevant to improving the department’s efficiency, but these are secondary benefits.

B. Ease of use: a demo helps to show if the proposed solution would be user friendly. In-house lawyers and other users in the company should be able to navigate the solution seamlessly. One would typically not want in-house lawyers to be overly occupied with explaining the new legal tech to other users in the company. Trying out available demos is immensely important to understanding the user experience.

C. Integration with existing solutions: another consideration would be the ability of the solution to integrate with other solutions in the company. A sales team, for instance, may intend for their Customer Relationship Management (CRM) module to be integrated with the legal team’s contract management system, or it may be a reporting dashboard that legal intends to be integrated with the legal tech or there may be an existing vendor payment workflow which a supply chain/procurement department intends to integrate with the contract management system.

D. Solution provider support: the support provided by the solution provider is also a consideration. Would the legal department be able to rely on good external tech support to address any issues with the solution post-deployment? How active is customer support, and how exactly would it be provided? Are there local vendors in-country that can provide support services, and if not, is the existing support sufficient to address the legal team’s concerns both effectively and efficiently?

E. Flexibility/adaptability: as legal functions continue to evolve, can the solution be easily adapted to accommodate new legal functions? Can legal operations staff or in-house tech support make simple minor adjustments to bring the solution in conformity with changing legal requirements?

F. Cost: costs would be considered relative to the value the solution offers to the legal team. Some cost-related factors would be, for example, are there other means of expanding functionalities of existing solutions to address legal users’ requirements without purchasing another solution? If legal is proceeding to purchase a solution, can the legal department confirm it is getting the best value for a particular solution or are there alternatives that can address the legal team’s requirements and are more cost effective to purchase and maintain?

G. Communication: it is important that the legal operations team is clear on the desired functionalities and come up with the legal department’s user requirements. Once the user requirements are clear, the legal operations team can engage the tech team (either internal or outsourced) to implement a functional solution for the legal team riding on existing licenses. Where there are no existing in-house solutions that can be adapted for the legal department, then external tech solution vendors can be engaged with clear instructions on the legal department’s expectations.

Tochukwu gives his perspective on the growing reliance on legal tech, stating, ‘over the last decade, legal departments have taken steps to digitise their manual processes. An example of a manual process I have seen would include activities such as keeping written registers with dedicated staff crosschecking these physical registers daily to ensure important events, reminders, or expirations were not missed. Over time, legal departments became more comfortable with adapting technology for digital record keeping with simple Microsoft tools, for example, Microsoft Word and Excel. This served as a precursor to implementing automations that generate automated reminders to specific staff’.

He continues: ‘Currently, Excel is popular for capturing data, but beyond Excel, other Microsoft office solutions like Sharepoint are handy for capturing data in a useable format. Key of course would be for legal teams to work very closely with Sharepoint implementation teams to ensure that the tool captures all required fields and the right data’.

These modern-day tech tools, although not initially developed for the legal industry, have been a boon for the sector. Many GCs and in-house legal teams rely on this type of software for a broad range of tasks. Ayobami stresses the ease at which off-the-shelf software can streamline processes, saying ‘automating the process through which various departments in the company initiate legal related requests. Technologies in this area, such as SharePoint, also help the in-house counsel to track the number of requests received, nature of such requests and departments with the highest requests’.

Tochukwu elaborates on this point, saying, ‘Sharepoint can be used to track legal requests, assign tasks and timelines, keep records, and so on. Other Microsoft tools like Power BI can be used to extract legal data from Sharepoint or other data sources like Excel to create rich and interactive dashboards showing legal data in a format that helps the GC take intelligent decisions. The visuals created by such tools also enable GCs to present legal data in a language that is easily understood by management teams. Other off-the-shelf solutions promise specific and detailed solutions to address particular legal functions, for example, Contract Management Lifecycle Solutions, Board Solutions, and so on.’

Of course, none of these tech solutions can be implemented without relying on tech support. This universal truth of modern-day corporate organisational structure holds fast in Africa, just as it does globally. ‘GCs require tech guidance to wade through the various technology offerings in settling for the most appropriate solutions for the legal department. It is on this premise that it is envisaged that lawyers with deep tech knowledge would be regarded as valuable members of the legal department’, says Tochukwu.

The issues with using off-the-shelf software by GCs shouldn’t be avoided, however. As Ayobami notes: ‘Whilst SharePoint has proven key in addressing some of these needs, there is a need to rely on customised or bespoke tools to meet specific needs and enhancements.’ Additionally, Ayobami says, ‘A major concern is the applicability of these tech products to specific needs. Tech products seem to be designed for companies in general and not specifically for the in-house counsel teams in these companies which means the in-house counsel teams need to adapt these tech products for their specific needs.’

However, ‘Obtaining internal tech support can be challenging. Tech support for legal operations is not often regarded as mission critical for internal engineering and tech teams,’ as Tochukwu explains. He continues, ‘it can also be challenging acquiring the right tech tool to support legal operations. Scoping out the department’s requirement and matching it with the appropriate tech solution while considering other factors like cost, adaptability, user friendliness, support, and so on, can produce serious roadblocks.’

Imagining an ideal legal tech tool, Tochukwu says, ‘it is common to see tech tools that address specific legal functions, but it would be good to see tech tools that can be utilised across all or at most of the available legal functions. A robust legal department management tool that legal operations teams and the GC can use that tool to ensure the efficient running of the legal department generally.’ This ideal tool would be the Swiss Army knife of tools, rather than just one tool in the toolbox. ‘For instance, rather than shop for a contract management tool, it would be good to be able to acquire a tool that addresses contract management lifecycle, dispute and litigation management, intellectual property management, plus the more complex type transactions involving mergers, acquisitions, and so on,’ says Tochukwu. ‘It would be great to have a tech tool that not only addresses all functions carried out in the legal department but can be adapted easily by legal departments or where necessary with the aid of their inhouse tech team to incorporate all new legal functions under the same tool.’

WSG: Africa Transformed

With its myriad cultures, economies and regulatory regimes, Africa presents a unique set of challenges for business. Add in the breakneck pace of technological change evident across the continent and it means that things are set to get even more complicated. Leading professionals from across the WSG network in Africa tell us how tech is disrupting the nature of legal practice, and what it means for Africa’s corporate legal teams.

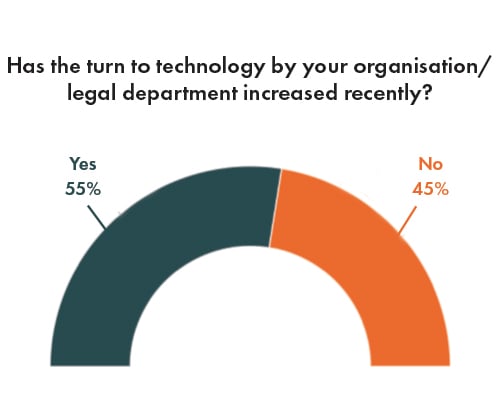

As one of the youngest and most dynamic populations on earth, Africans have a natural affinity for change. It is therefore no surprise to see that those surveyed in this latest edition of the WSG legal technology series, produced together with the GC magazine team, showed a clear openness to new ways of working. And that’s a vital quality, because African legal teams are among the most active in adopting new technologies, and in turn, pushing their law firms to also embrace change.

‘The Nigerian market has largely embraced and is increasingly embracing legal-specific technology in solving clients’ issues,’ explains Davidson Oturu, a partner in the Lagos office of AELEX. ‘Electronic filings for court documents are now becoming more prevalent with courts gradually eliminating the process of physical filing and building a database of case files and documents that are easily traceable. There are also legal technology platforms that are making it easier for clients to access simple agreements like a power of attorney and land documents.’

The role of GCs in navigating pandemic-related restrictions gave many a new prominence within their organisations, but at the same time, it also gave them a chance to consider whether a new way of working was possible. The tech-backed tools GCs were forced to rely on during lockdown quickly became an established part of working life – and it’s not one that any intend to give up in a post-Covid environment.

‘There is a fear that much of the progress made in the past years will be undone with return to work. The legal tech sector however continues to evolve with firms and in-house teams slowly feeling their way into other digital means of legal service delivery,’ says Ridwaan Boda, executive – technology, media and telecommunications at ENSafrica.’

The legal tech sector in South Africa has come into its own in the past year or two, largely necessitated by work from home and the need to digitise practices. Most clients still opt to work from home and prefer solutions which enable seamless communication.’

The growing prevalence of legal tech is something WSG member firms across Africa encounter daily. From advising on legal tech platforms to thinking about new ways of delivering service to clients through technology, we are constantly being asked to harness the same entrepreneurial spirit that fuels our clients’ successes.

Beyond this, we have seen technology transform everything from court procedures to government registries in varying degrees across the continent. At the same time, Africa-originated start-ups have brought new eDiscovery, document automation, and legal practice management platforms and services to the market at a remarkable speed.’

Some of these innovations have been codified in laws such as the recently passed Nigeria Start-up Act,’ adds Oturu. ’[This Act] introduced a start-up portal for easy engagement with all relevant regulators [and] made some excellent advancement towards the adoption of legal tech for effective court system management in Nigeria. The rules provide for electronic filings and virtual proceedings, all of which were previously alien to the practice of law in Nigeria. In addition, we have seen the introduction of several software tools that have aided lawyers as well as clients in gaining access to legal information.’

These legal information providers include LawPavilion, an electronic law reporting solution founded in Lago in 2007, Lawpadi, a self-service legal information and template solution, and information and service platform DIYlaw, perhaps the most internationally recognised law tech start-up in Nigeria.

The growth of legal technology has also changed the risks facing businesses. Increasingly, the world in which GCs operate is shaped by questions of cybersecurity, data transfer and international regulatory harmonisation. These issues are particularly pressing for GCs based in Africa, where a diverse set of economies and regulatory standards can make it essential to find smart solutions.

Lawyers across the world face cultural barriers when it comes to adopting technology, and the journey is something we need to undertake as a profession. For those of us working in Africa, GCs will lead the charge. We have seen an in-house community that is passionate about technological solutions, passionate about doing things in new and more effective ways, and passionate about reimagining the role of lawyers. Importantly, as this report shows, they are not simply looking to copy the work being done elsewhere, but to invent their own way of doing things.

It has also, adds Oturu brought about a better working relationship between the law firms and clients. ’The innovations in legal tech have brought improved legal services to the clients, as seen in the prevalence of case management and online dispute resolution systems. Social media platforms particularly have been a major contributor to the growth of legal tech in Nigeria. They have also created a [space] where potential clients can connect and gain access to lawyers across all fields of specialisation.’

At World Services Group, being a part of this change isn’t enough for us, nor our global membership. We take great pride in empowering our member firms to innovate and embody the evolution that we strive to affect across the legal profession.