The 2023 Turkey international focus is coming soon. Contributors will include:

Balay, Eryigit & Erten Attorneys at Law

Hamzaoglu Hamzaoglu Kinikoglu Attorney Partnership

Solak & Partners

The 2023 Turkey international focus is coming soon. Contributors will include:

Balay, Eryigit & Erten Attorneys at Law

Hamzaoglu Hamzaoglu Kinikoglu Attorney Partnership

Solak & Partners

In 2021, The Legal 500 partnered with Irwin Mitchell to produce our ESG Risk Report. Since then, we’ve seen environmental and social issues dominate corporate agendas, but comparatively, there has been little focus on governance. This is despite the fact that implementing a robust corporate governance plan provides a framework which will maximise protection for the stakeholders’ interests, reduce reputational risks and help companies to gain an advantageous position in the market.

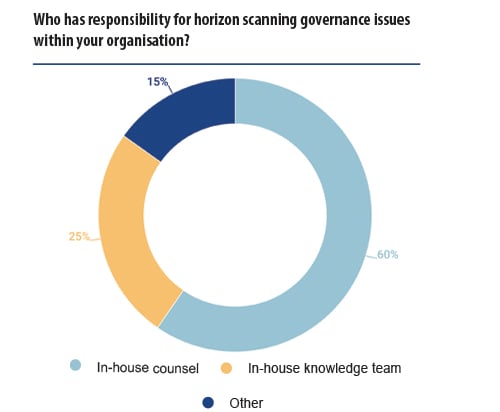

Traditionally, board directors have, almost exclusively, been responsible for governance-related matters; however, as the role of general counsel (GC) evolves, and as the results of our survey suggest, board members are looking to their in-house counsel to pre-empt and reduce governance risks. Further, with many sustainability questions and issues not yet being clearly addressed by regulation, in-house teams are rightly being asked to work with people across their business to put resilient governance and reporting frameworks in place.

We surveyed over 115 in-house lawyers worldwide to gather their insights for how to develop and implement successful and forward-looking governance programmes.

In-House Legal Research Team – GC Magazine

‘Effective and transparent governance is an essential part of the business toolkit for companies that want to thrive in today’s rapidly evolving and competitive business environment.

‘Effective and transparent governance is an essential part of the business toolkit for companies that want to thrive in today’s rapidly evolving and competitive business environment.

Although the G in ESG rarely makes the headlines in the same way as environmental and social factors, good governance is fundamental for building trust in and across any organisation, as well as long term sustainability and value.

How businesses operate is increasingly influenced by a wide range of stakeholders including employees, customers, suppliers and communities as well as shareholders and investors. Their priorities and values go far beyond regulatory and legal requirements, and the bottom line. For GCs and in-house teams, this means that the landscape of risks and opportunities that they oversee has changed considerably in recent years, and the pace of change continues to accelerate.

I’d like to thank everyone who contributed to this research for sharing their time and insights with us. We hope you’ll find this report a useful resource for guiding your business in developing and achieving its governance aspirations. But this is just the start of the journey, and we’d love to hear your thoughts on how governance and the role of the GC in progressing this agenda will evolve

from here.’

Hannah Clipston, Director of Strategic Growth, Irwin Mitchell

Board members across the world are familiar with the theory of effective governance. It embraces several key aspects, including regulation, compliance, good practice and board ability. Over the past few years, a two-fold evolution has meant the traditional appreciation of governance has moved on from the textbook approach. First, the role of general counsel has undergone significant transformation in the past decade, which has broadened its scope to strategic partner, prompting companies to expect corporate counsel to – among other things – provide advice and strategic guidance on corporate governance and all ESG-related matters.

The second evolution concerns the concept of governance itself. The concept has historically been used to describe transparency and accountability within the corporate sector. As business models have evolved and become more complex, companies have used governance models to enforce ethical corporate behaviours, both internally as well as with external stakeholders.

The past few years have seen a proliferation of statements, proposals and revised codes of corporate governance. While some of these statements reaffirm conventional doctrines and practices, others call for efforts to better align corporate activities with society’s interest in building a more inclusive, equitable, and sustainable economy.

In today’s market, with a customer base that holds expectations that can exceed a business’s legal and regulatory obligations, and is becoming more discerning on where and with whom they do business, ensuring alignment between a business’ purpose and what it does in practice is critical in building trust, both internally and externally.

In-house counsel have a pivotal role to play in the development and implementation of effective governance programmes that will steer the way a business conducts itself and ultimately, its success.

The research identified three key factors in creating a governance framework that is successful. These issues were repeated by the in-house community, regardless of sector and geography.

Focus on engagement: before creating your framework, spend time on gaining buy-in from all levels of the business including the board, the wider leadership team and team leaders who will be accountable for implementing the framework. Take time to listen to the business about their day-to-day work, challenges, expectations and what works well already. Socialising ideas and changes is important too.

Furthermore, ‘always listen, learn and adapt, because the theory doesn’t always work in practice’.

When developing the framework, keep it simple and use training to ensure that everyone is clear on what the objectives and expectations are and why they are important. You may also consider starting small with some key areas, gaining traction and then growing from there, rather than introducing wide-ranging changes in one go.

‘Make sure you have a progressive plan. Start small and get buy-in from leadership and employees, and then move to bolder actions’.

Create a framework that is specific to your organisation, its goals, strategy and risks as well as the regulations it is bound by. Hiring consultants or carrying out research within your sector will help you to gain insights and ideas which can be adapted into achievable and measurable governance objectives that will resonate within your business.

‘Every organisation is unique. Connect with your organisational requirements to propose a customised governance module that offers a mix of innovation and dynamism without making the stakeholders uncomfortable.’ Or, more succinctly put: ‘don’t copy and paste’.

This report considers each of these factors in more detail and provides practical guidance on how to achieve each of them.

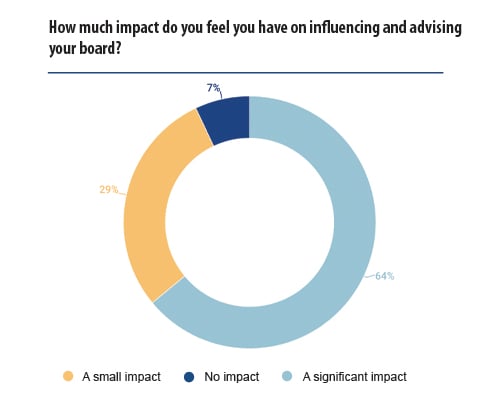

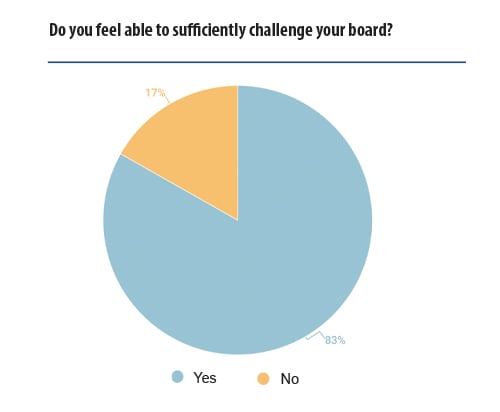

One of the key factors for achieving good governance identified in the survey was the ability for GCs to influence the board, and it is positive that the majority of the respondents felt they could both influence and challenge their board of directors.

GCs play a crucial role in advising the board when it comes to risks, compliance and regulatory-related issues. But to be truly effective, GCs need to look beyond their immediate area of expertise. As one GC said to us, ‘we are not only lawyers, we are part of the business. I think my advice to other GCs would be: you have to be part of the board, because first of all, you are part of the business.’

Overall, even though a vast majority of GCs expressed the ability to sufficiently challenge boards of directors, the respondents expressed an interest in having more direct engagement at board level. This would help them to have a better understanding of the business drivers and focus on the ways the legal ecosystem can support them. ‘Our role is to prevent any risks the company faces in its business and projects. Direct access is the best way to influence it’, another interviewee explained.

The advice from our respondents, for those looking to increase their influence in the boardroom can be split into three key areas:

First and foremost you need to be in the boardroom, and once you are there:

Always keep one step ahead in order to proactively provide training, guidance and advice

Articulate the value of good governance

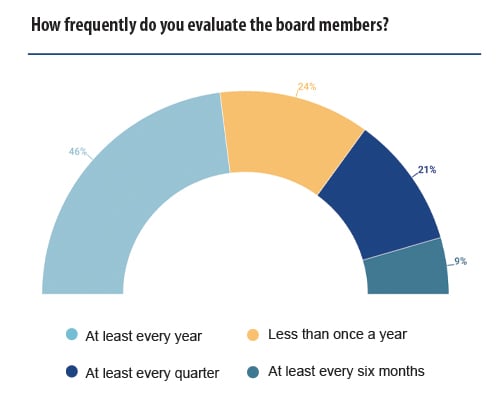

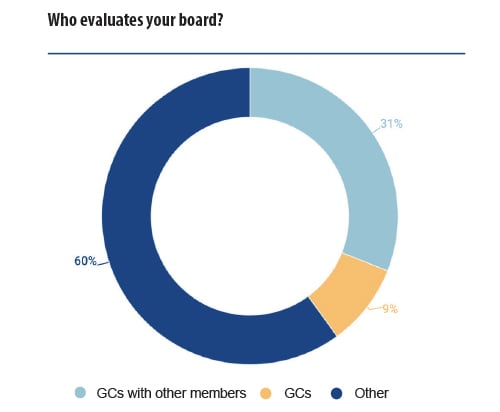

When you have achieved buy-in from your board, or are trying to do so, understanding the evaluation procedure for the board is critical. The ideal scenario is to link good governance, along with other E&S targets, throughout the organisation with reward at a board level. However, that can only occur when there is a clear and transparent board evaluation culture and procedure. Here, we look at how boards are currently evaluated.

Typically, the board of directors carries out a self-assessment where it evaluates itself, often alongside an external independent group, such as a consultancy or audit firm. Some boards of directors take the view that relying solely on self-assessment may provide either the perception of a conflict of interest or may lead to a biased assessment. Therefore, in these cases, this evaluation is carried out by an external auditor to provide, in the opinion of one respondent, ‘an objective view’ of the status of the company.

As one respondent notes, due to the structure of many companies, members of in-house counsel may be part of developing a governance programme, but they generally do not participate in follow-up assessments of whether compliance has been met. One GC noted: ‘As an employee I do not evaluate the board of directors. The board does a self-assessment regularly with the assistance of an external consultant’. If, however, as some companies have done, they brought in-house counsel onto the board of directors, this would allow GCs to continue their involvement in governance frameworks beyond their initial development.

Notably, 60% of respondents noted that GCs did not participate in evaluating the board. Within this cohort, the responses included self-evaluation by the board; evaluation by an internal team not connected to in-house counsel, such as shareholders; and/or evaluation by an external team.

Interestingly, in some cases, even when governance standards had been adopted, some respondents expressed disappointment about a lack of any standards for board members. One respondent said, in response to our question as to who evaluated the board of directors, ‘No-one. Unfortunately’. This shows that while even if good governance policies have been set, that is only the first (and perhaps) easiest step. Without a way to reliably evaluate whether standards have been met, proposed governance programmes will be no more valuable than the paper they’ve been printed on.

The responses by in-house lawyers made clear that they felt linking board performance on good governance to objectives and reward, coupled with an external and independent entity to evaluate performance, provides a valuable incentive for the board to promptly implement governance goals in measurable ways. Unfortunately, this has yet to happen in many organisations and continues to be an area for improvement.

A follow-up survey addressed both measurement of performance of boards and remuneration of directors. The first question’s respondents gave a strong split, with one third noting performance was formally measured against specific governance KPIs.

Some responses noted they implemented the S&P’s DJI ESG scores, while others had developed bespoke policies, with one noting their 2030 agenda consisted of ‘30 cross-company goals that align to outcomes of sustainability, equity and trust’. Others emphasised corporate compliance, gender equity and diversity, while some highlighted a ‘specific focus’ on ‘ethical-related risks’ or a ‘holistic view on enterprise risks’.

The responses to the second follow-up question track the first, with a little under one third noting that their board of directors had remuneration policies directly linked to achieving specific governance KPIs.

Cross-referencing the two questions, we discovered a full 54% of respondents had neither any formal measurement in place, nor any remuneration to boards of directors directly linked to achieving specific governance KPIs. Only 21% of respondents had both formal measurements in place as well as a form of remuneration in place to boards of directors directly linked to achieving specific governance KPIs.

This demonstrates that there is still a long way to go for boards to be collectively and personally accountable for governance in their organisations. However, it is clear that progress is being made and it will be interesting to evaluate if those who have created a firm link develop a better governance culture and improve business performance as a result.

Another key issue that companies are faced with when considering good governance is the diversity of their board, including gender, ethnicity and diversity of thought among others. While this is often something in-house advisors may struggle to influence it does bear consideration, including when looking at how to influence your board and what issues may have differing levels of importance to them. Here, we look at the thoughts of those surveyed on the diversity of their own boards.

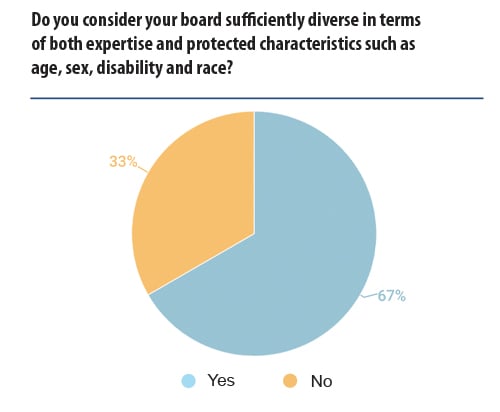

The statistical data provides a positive sign regarding diversity on boards of directors, with two thirds believing their boards of directors to be sufficiently diverse. This reflects a strong focus in recent years on board diversity, with the associated improvement in governance it is felt this can bring. It was, however, noticeable that the feedback from GCs who responded with ‘No’ painted a general picture of frustration from in-house counsel that their board of directors were generally older, white men, and what steps had been taken to improve diversity regarding gender were, in the words of one respondent, ‘minimum and limited’.

However, while some expressed frustration at failures to diversify boards of directors, others expressed optimism towards future improvements: ‘We have taken actions, including raising the non-diversity issue with the local board and explaining to them how this lack of diversity will be perceived’. It should be taken as a positive that improvements have been made and that action continues to create more balanced and diverse boards which are essential for tackling increasingly complex commercial issues, often requiring innovative and creative solutions.

‘Increasing diversity at board level helps to create more inclusive and collective governance, and strengthens an organisation’s ability to respond to and anticipate change in ever-evolving markets and client bases. Greater diversity has been shown to bring about improved productivity and performance, a more responsive approach to client needs and increased innovation and creativity through a sense of belonging and the power of diverse thought. Therefore, a diverse range of board members brings with it a valuable range of perspectives and experiences to decision-making and problem-solving.

You also can’t underestimate the power of senior role models, particularly at board level, for under-represented groups and the impact this has on an organisation’s culture. While change on this doesn’t happen overnight, more can be done to recognise where there is a lack of diversity at board level and in wider decision-making groups and to seek out more diverse views to inform decision-making. Board members can act now and challenge views presented to them to ensure that diverse views have been taken into account in shaping proposals and policies prior to approval, while work takes place to increase the overall diversity of the board and the talent pipeline within an organisation’.

Charlotte Delaney, Diversity and Inclusion Manager, Irwin Mitchell

‘Looking to the future, businesses are having to think more and more about how to generate innovation in order to respond to increasingly complex customer needs. Within Irwin Mitchell, we want to ensure that our products and services evolve so we are constantly exceeding client expectations. We know this is dependent upon attracting and retaining diverse talent and future leaders so we can benefit from different perspectives and experiences at all levels across our business. This starts with a commitment to widening access and increasing social mobility and by participating in initiatives like our new mentoring programme with City University, access to work experience with PRIME and increasing our apprenticeship offerings, we provide opportunities for students who might not otherwise have considered a career within the legal sector.’

Satinder Bains, Partner and Chair of Irwin Mitchell’s Social Mobility Colleague Network, IM Aspiring

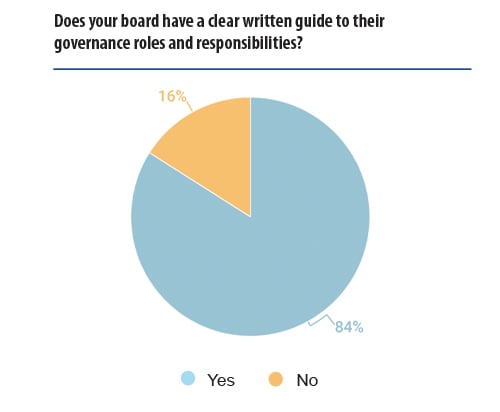

Ensuring your governance framework is simple and well understood is key to its success. Complex structures lead to a lack of understanding and engagement. This section looks at some of the challenges to embedding a good governance structure, and with winning buy-in from the business’ people at the top of the list, the importance of a simple, well understood and articulated plan cannot be overstated.

We asked about the main challenges to achieving good governance in an organisation, and while some cited difficulties caused by external factors such as local culture and politics, the majority of responses related to internal factors that GCs can actually influence.

Employee buy-in is considered the main challenge to achieving good governance, and this is noted as particularly tricky in organisations with high staff turnover, where employees are located over multiple sites and jurisdictions, and when people are already time-poor. But clear and concise messaging will go a long way to garnering buy-in. In addition, small steps can help bed in the framework, creating a simple starting point which can then be built on.

As one GC we spoke to pointed out: ‘The biggest difficulty is communicating clearly and in a manner that cuts through the noise of so many other regulatory, reputational and business demands on the attention of all stakeholders, including, not least, employees’.

Similarly, boards and other stakeholders will be more inclined to support governance issues if they have clarity on the costs of taking or not taking certain actions.

Formulating a simple framework which includes measurable principles provides valuable data which can be used to the advantage of the business. 75% of those surveyed said they use governance data and achievements in their marketing to employees and new hires, as well as customers.

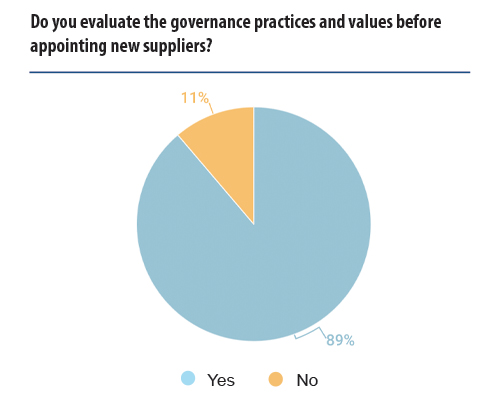

At a time when GCs are increasingly looking for ESG as part of their own supplier procurement process, having readily available and clear metrics on ESG compliance, including governance, is becoming a must-have for any business who wishes to grow, recruit and attract investment.

‘A robust governance framework is critical to our Responsible Business strategy. As well as ensuring that we set sufficiently challenging KPIs and objectives around our work, we engage external partners and participate in a number of benchmarks and accreditations to measure our progress and ensure that we continue to make an impact. We report on our performance in our annual Responsible Business report.’

Kate Fergusson, Head of Responsible Business, Irwin Mitchell

A key factor in success was making the framework specific to your organisation. This will necessitate in-house counsel understanding the needs and issues within their business and prioritising their governance objectives accordingly, which will then naturally flow into the framework for your organisation.

This section considers the priorities and aspirations from those surveyed, to provide support when considering some of the aspects you may wish to examine while looking at your own specific governance framework.

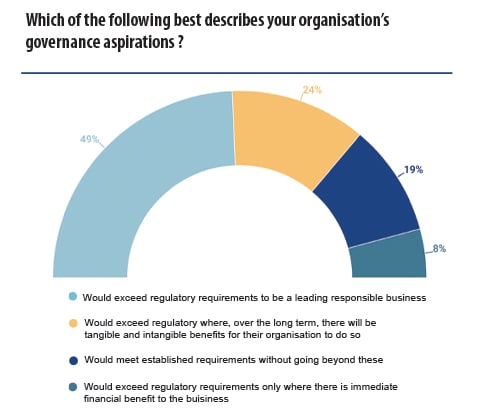

In our study, we found that most companies’ governance aspirations go beyond regulatory requirements. 48.7% of those interviewed stated that they would exceed regulatory requirements to be a leading responsible business because, simply, it is the right thing to do, rather than for commercial

gain. A further 23.5% say they would exceed regulatory requirements where, over the long term, there will be tangible and intangible benefits for their organisation to do so.

These figures demonstrate that for many, governance has moved on from being seen as a compliance exercise to a more strategic framework built to support sustainable business growth and impact.

19.3% of those surveyed would meet the established regulatory requirements without going beyond these, and the remaining 8.4% would exceed regulatory requirements only where there is an immediate financial benefit to the business, such as on cost savings.

‘The direction of regulation and of client, colleague and community expectations around Responsible Business are clear and accelerating. Today’s aspirations and “nice to haves” will soon become tomorrow’s bare minimums. And changes of this scale in business take time to implement effectively. So a significant factor for the long term sustainability of all businesses is anticipating successfully the direction in which change in the business ecosystem is happening – and not just looking at today’s position (as you will fail to meet future needs if you do) – and then starting the change process proactively in that direction so that the needed changes are completed in the business in line with or even ahead of, rather than behind, the competition.’

Bruce Macmillan, GC, Irwin Mitchell

For the majority of respondents, the main focus for the year ahead is on their governance policies, frameworks and programmes. For some, it is about putting these into place while others are looking to refresh and update. Improving accountability and compliance also scored highly.

Looking at specific types of risk, unsurprisingly ESG tops the list, and drilling down further it is environmental issues that are highest on the agenda. This reflects the general trend in society and from stakeholders to ensure these issues are considered and understood, and appropriate governance procedures put in place to manage the risks.

As to cybersecurity and data privacy, respondents pointed out how organisations benefit from a comprehensive, integrated and centralised strategy for achieving data privacy compliance. Data sharing, they say, should have stricter controls and policies, which implies either current legislation is not being complied with or does not go far enough. Organisations should develop more solid data security compliance methods to track personal data in accordance with legal standards.

‘We often see that organisations don’t have a complete picture of all the data sharing happening either from an intra-group perspective or with third parties. This is particularly the case with increased globalisation – there is often data export which is overlooked. For example there can be line management in groups done by managers in other group companies and other countries. IT and tech contracts often have an international aspect somewhere in the supply chain. Since the compliant export of personal data is a hot topic at the moment for the ICO and the European regulators it is important to understand what data sharing and export is happening and to ensure that it is compliant. Things are complicated by the fact that the data export rules and standard export contracts have changed recently. The old approach of signing EU standard contractual clauses and forgetting about them doesn’t work anymore. The issue will be further magnified once the UK data protection reform happens. We don’t yet have sight of the draft legislation after the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill was scrapped but we understand that it is still on the cards.’

Joanne Bone, Partner – Commercial and Data Protection

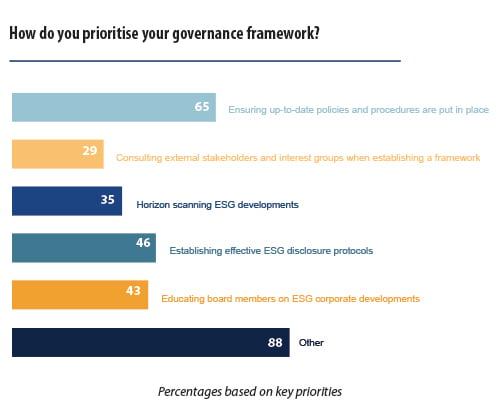

In terms of priorities, over 60% of GCs stressed the importance of having adequately up-to-date policies and procedures in place. This is a key starting point for any governance framework but it must be specific – companies should not adopt policies for the sake of it where they are not necessary or adding value. Over 40% consider the most pressing matter as the establishment of effective governance disclosure protocols and educating board members on governance developments. Less than half of the people interviewed see the necessity of consulting external stakeholders and interest groups when establishing a governance framework (29.41%) as a number one priority.

Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that under the category ‘other’, the majority indicated that their priority lies in organising training for all stakeholders to better achieve good governance and create a sustainable change. When it comes to taking the ultimate responsibility for achieving good governance, the general feedback is that this is a collective task, however,

the board of directors and key managerial personnel have the last word. The board’s purpose is to support corporate performance and establishing clear Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and appropriate measures for evaluating against those KPIs. Linking that success (or failure) to reward helps focus the board on the importance of good governance.

This reflects the contents of this very report: that board engagement, simple policies which employees can understand and are trained on, aligned with a framework for for your business, are how you can achieve good governance success.

‘Creating a Culture of Compliance, as we are doing, needs to have a clear metrication of what is right – directionally and in terms of what a material improvement or deterioration looks like; clearly and openly spelt out to leaders and team members – we use a Balanced Scorecard with Key and Leading Performance Indicators; and then their needs to be a clear, explicit and adhered to approach that makes good or poor compliance a material reward and promotion issue.’

Bruce Macmillan, GC, Irwin Mitchell

Having established and embedded a good governance framework, the work of an in-house lawyer is not complete. Good governance practice continually evolves. This report has already flagged the importance of independent monitoring of compliance and performance against the background of the governance framework set. However, from a commercial perspective, the focus of a business will shift to reflect new trends and demands from stakeholders, customers and employees.

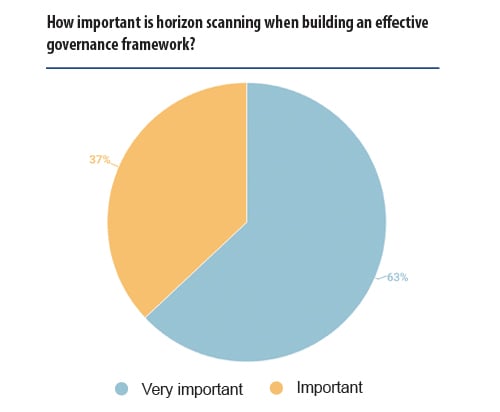

Keeping your governance policies and procedures up to date requires a strong emphasis on horizon scanning, together with regularly revisiting your materiality assessment to understand the key issues for your stakeholders and which will impact your business and governance framework.

Like the captain of a ship, in-house counsel need to be able to identify ‘hidden icebergs’ and thorough horizon scanning will detect future disruption along with new opportunities to build into responsible business plans which will positively impact their business and society. Effective horizon scanning also provides decision-makers with the time to plan their response, and clear communication with external partners ensures those in the supply chain have the opportunity to ‘stay ahead of the game’.

As well as relying on monitoring services and updates from external experts including law firms, auditors, regulators and the government etc, the GCs surveyed take advantage of networking events, training and digital forums such as LinkedIn groups to ensure they are keeping up to speed with what is on the horizon.

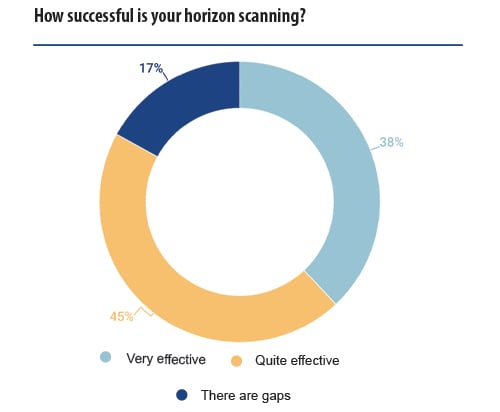

The majority replied that the horizon scanning in place is effective in identifying governance issues before they arise. However, gaps persist. Under the gap section, interviewees expressed a willingness to have more resources allocated within the in-house legal team. Until then, working alongside your legal advisors and other sources of updates should be a priority to ensure your governance framework remains fit for purpose.

The pace and scale of societal, economic and environmental challenges facing us means we need to generate innovation and creativity within our organisations to quickly devise and implement solutions. This will require diversity of thought and openness to collaboration across our own business and the wider economy.

By leading the focus on effective governance against measurable KPIs which are understood and supported, GCs can be at the forefront of this challenge, making a difference to not only their organisations, but to society as a whole.

Establishing a successful governance framework relies on many different things but its importance to a business should always be remembered. The G in ESG is often overlooked, but for a business to be successful it should be a core part of its focus, from the board to employee. The role of the in-house lawyer in achieving that can look daunting, but by focusing on getting the right engagement, keeping your plans simple and being specific to your organisation, you can achieve success.

In the column on the right, we have set out a checklist from the research to help you assess where you are on your governance journey, and what the next steps are for you and your organisation.

Communication

Compliance

People and culture

The merger talks-prompted exodus from Shearman & Sterling continued in recent days with the loss of EMEA and Asia M&A head Philip Cheveley to Sidley Austin in London.

The blow to Shearman will be even more keenly felt since the move represents a reversal for one of its stated ambitions to focus on corporate, and because Cheveley only joined from Travers Smith less than two years ago, in March 2021.

Merger talks between Womble Bond Dickinson (WBD) and BDB Pitmans have been called off, the firms announced on Wednesday (1 February) in a joint statement.

Talks of a combination first became public in October 2022, when a story on RollOnFriday prompted WBD and BDB Pitmans to confirm that they were in discussions around a potential merger, albeit early stage.

Continue reading “End of the road for Womble Bond Dickinson merger talks with BDB Pitmans”

‘Disputes arise when there is disruption, and it seems to me there’s just about every type of disruption at the moment.’

With this, Julian Copeman, a disputes partner at Herbert Smith Freehills neatly summarises market expectations for 2023. It’s going to be a busy year. Continue reading “‘With economic downturn, the need to pull the trigger on claims intensifies’ – leading City litigators look at the key disputes trends for 2023”

The City lateral market has been abuzz with activity, as major moves in the infrastructure, corporate, funds and real estate sectors have proven.

Paul Hastings has hired Linklaters co-heads of infrastructure Jessamy Gallagher and Stuart Rowson in London, significantly boosting its City credentials.

Continue reading “Revolving doors: Linklaters loses three as Macfarlanes takes Sidley funds head”

Globally speaking, it has been a tough week for Shearman & Sterling, which lost several partners amid rumours of merger negotiations with Hogan Lovells. King & Spalding took two partners; M&A-focused Thomas Philippe joined in Paris, while project development expert Dan Feldman arrived in Abu Dhabi.

Gibson Dunn brought in three partners from Shearman, as it announced a new office in Abu Dhabi. Legal 500 Hall of Famer Renad Younes was a headline arrival, having served as global head of finance and managing partner for the Middle East at her previous firm. Samuel Ogunlaja will also form part of the new office and focuses on project development and finance in the energy and infrastructure sectors. Jade Chu has joined the Dubai office. Continue reading “Revolving doors: Losses for Shearman as City elite target investigations”

Cleary Gottlieb has brought in Travers Smith’s respected head of private equity Ian Shawyer (pictured) to strengthen its City practice, as the firm continues its recently redoubled strategy of strengthening its corporate bench.

A Travers stalwart, Shawyer has spent almost all of his 25-year career at the firm, save for a brief stint at Weil Gotshal in 2005. His expertise spans a range of deals including leveraged buyouts, consortium deals, bolt-on acquisitions and carve-outs, while his client list includes Bridgepoint Development Capital and The Carlyle Group.

Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan’s London office has released a solid set of 2022 financials, headlined by a 10% increase in profit to £94.87m. There was also an increase to the top line, as it rose 5% to £133.58m, resulting in an impressive profit margin of 71%.

The figures saw the firm return to its familiar growth trajectory after a flat performance last year. However, this year’s numbers were still below the heights of 2020, when the litigation specialist enjoyed an 11% increase in profit and a stellar 20% hike in revenue.

Continue reading “Quinn shrugs off partner departures with 10% City profit boost”

Pallas Partners has taken advantage of its alternative business structure (ABS) to appoint its first non-lawyer, chief administrative officer Linda Penfold, to the partnership.

Penfold has more than 20 years of leadership experience in global law firms, managing operations across multiple jurisdictions and, at Pallas, has a mandate to lead the business services functions, office operations, and add strategic vision in improving client service. Continue reading “‘Why shouldn’t she?’ A new take on partnership as Pallas takes first non-lawyer into the fold”

The paralysing shock brought by the global pandemic may now feel like a distant memory, but there is little doubt that a new era has begun. In this ‘new normal’, as the media labels it, the consequent need to treat digitalisation as an essential ally to carry out daily tasks has forced businesses to approach technology from a whole new angle. Even at the peak of the Covid-19 crisis, The Legal 500 never ceased its interaction with legal professionals worldwide. As the world reopens and in-person global events are now an actuality, we have had more opportunities to speak with our vast global in-house and private practice communities and it appears that the legal industry is at the forefront of this technology debate. The developments arising out of the pandemic have prompted legal teams across the globe to recognise the need to become more responsive, agile, adaptive, and resilient, while the introduction of legal tech is gaining momentum and challenges traditional ways of providing legal services.

The Legal 500 has partnered once again with the independent law firm network World Services Group (WSG) to produce a comprehensive survey that aims to investigate the usage and impact of legal tech on in-house departments worldwide. The ‘In-house Technology – Global Edition’ concludes our In-house series, which covers the subject in Europe, Latin America, Asia Pacific, and North America. It includes extensive coverage of the Middle East and Africa, the two regions in which legal technology has made substantive progress in the past couple of years. The series also provides an update on recent evolutions in the rest of the world, the challenges general counsel face, and how they expect technology to assist them in overcoming difficulties. Additionally, and for the first time in a special report, we have spoken with over 200 general counsel around the globe and provided bespoke statistics to depict a more global perspective of this phenomenon.

The role of general counsel is changing rapidly, and the remits covered by legal teams are ever-growing, to a point where they need to continually and speedily digest a substantial influx of information. In this context and with the aim to provide a platform for the legal profession to exchange ideas with peers, learn from each other and find solutions together, The Legal 500 looks forward to engaging with in-house practitioners to follow up on the topic of legal technology and how they implement it within a team in the future.

Allan Cohen

Research Editor | Special Projects

GC Magazine

Nathan Oseroff-Spicer

Research Editor | Special Projects

GC Magazine

On behalf of the entire global World Services Group (WSG) network, I am delighted to welcome you to the fifth and final edition in this regional series of

GC: In-House Technology special reports.

Over the course of these five reports, GC Magazine in partnership with WSG, have explored the role technology has played, and continues to play, in modernising the legal profession. This work has been grounded by the contributions of in-house legal leaders and experts from all across the globe, with hundreds of interviews and thousands of hours of research condensed into this multi-part series of work. The reports provide cogent insights into trending technologies, and general counsel members are utilising these tools and solutions during these ever-changing digital times.

Since 2020, the world – and by extension – the legal profession, have endured a level and pace of change that previously would have defied imagination. The series has been particularly timely, too, in the sense that technology has never been more crucially relied on – and by association, closely examined – since the advent of Covid and its effects on our professional lives.

As the world gradually moves into the post-pandemic period and returns to a semblance of normality, one of the most important factors for future success will be how the legal profession applies the lessons from these challenging times – particularly where technology is concerned.

At WSG, we have long been an ardent supporter of the modernisation of the legal practice via technology – with a focus on the power of technology to help WSG members stay competitive and exceed client expectations in rapidly changing environments.

In closing, I would like to offer my sincere gratitude to all who have contributed to this series of reports and made it the success that it has become. At WSG, we are immensely proud of this body of work and its contributions on the impact of technology and the legal system, both now and in the future.

Herman H. Raspé

Chair

World Services Group

Partner

Patterson Belknap

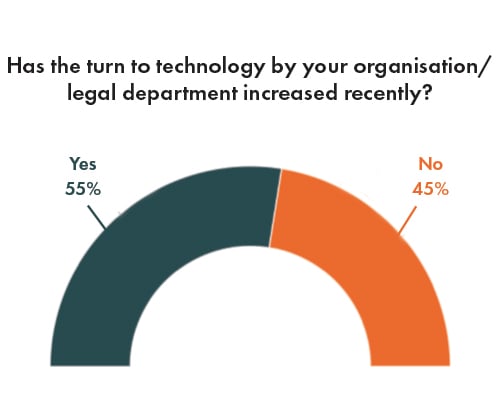

The speed at which technological advancements occur is pressuring legal departments to embrace change. We have asked general counsel if the turn to technology by their organisations has recently increased.

The findings report that 55% of the respondents answered ‘Yes’ to the question, indicating that for all surveyed, in-house legal teams operated under the assumption that recently increasing legal tech was either necessary or a pre-emptive decision. This desire of their companies is guided by basic market forces from without to increase efficiencies and internal pressure from legal teams to alleviate increased pressure on legal teams.

Note that the question was limited to recent increases in implementation of legal tech, therefore the set of respondents to the question that answered ‘No’ may very well have relatively recently introduced legal tech or already be using legal tech. Such a coarse-grained answer does not capture any variance in the beliefs or attitudes of GCs that conducted the survey. However, even with this coarse-grained question, the results indicate that as today’s legal departments continue to evolve in response to corporate demands and become more complex, driven by the introduction of new and more demanding requirements, in-house legal teams appear to think legal tech is the best option to respond to such a challenging environment. This reflects the belief that implementing software and other tools scales up in ways that hiring more in-house counsel and other members of legal teams cannot.

One possible inference that can be drawn from the data is that within this 45% that affirm there has been no recent increase in legal tech, there is a subset of this group that belong to organisations that have not been concerned with implementing legal tech. In these cases, part of the reason is likely found in the limited budget and conflicting priorities within corporations. This subset of GCs may want or even need new forms of legal tech to alleviate increased workload; however, due to internal tensions within a company, they may be unable to secure the necessary tech.

Additionally, in some cases, it cannot be ruled out that an increased market of legal tech produces a paradox of choice: there may be too many options available on the market at this point, cognitively overwhelming legal teams and GCs who wish to implement legal tech that would be right for them, but feeling stressed and incapable of making appropriate decisions without a clear preference for an option that appears superior to other options.

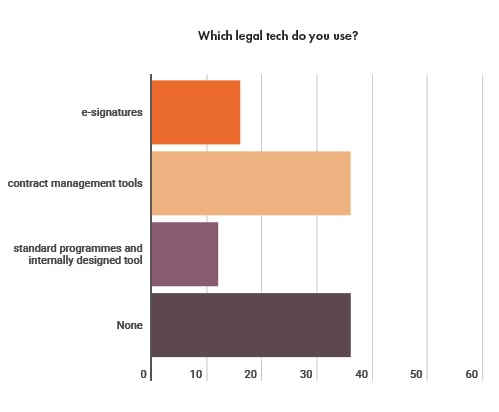

Results show that more than 64% of the respondents adopted legal tech to carry out daily tasks. When taken alongside the previous question, we see that at least 11% of respondents that answered ‘No’ to the question of whether they have implemented new legal tech recently already have some form of legal tech in place. This gives a more accurate picture where things currently stand, with 36% of all GCs surveyed currently not implementing legal tech.

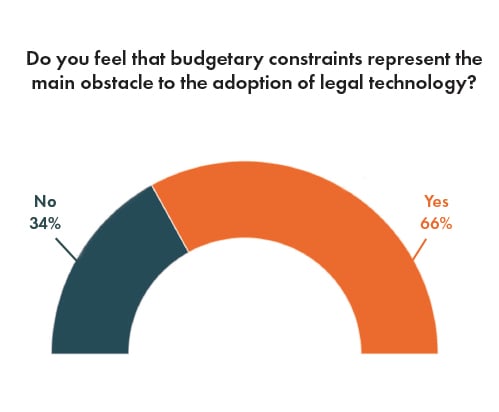

Of this 36% that did not implement legal tech, their responses are illuminating. In the opinion of some respondents, their decision to not implement legal tech was due not to any decision made by in-house teams, but due to external corporate pressure. A common reason behind the rejection of technology seems to be budgetary constraints, defined by one general counsel as ‘too expensive to be used for in-house tasks’, an argument sustained by another counsel who supports that before making such investment, the department must assess the value that legal tech brings to the team.

Of note, no respondents gave any indication that they were purposefully avoiding implementing legal tech out of any concerns about its effectiveness or operating under the assumption that legal tech was a fad; rather, one illustrative response helps clarify how little funding in-house legal teams receive: as GC notes, ‘we only use free access databases. Other tools seem too expensive for their use on an in-house team’, providing a clearer picture of the corporate environment in-house legal teams find themselves in.

Between the set that do implement legal tech, however, over 36% use contract management, review, and research tools. Over 16% of the respondents use e-signatures software, and the remaining 12% use more standard programmes such as the Office package and internally designed tools. A common maxim in corporate procurement is ‘fast, cheap, good. Pick two’. If you’ve ever gone through a procurement process you know that sometimes you will only have one option. We can see this in play with the types of legal tech that have been implemented, ranging from bespoke, customised legal tools or highly complex AI-based tools to household names, such as Word or Adobe. Bespoke legal tech will likely be good, but it won’t come cheap, and procurement may not even be fast; however, off the shelf corporate software may be fast and cheap, but it may not get anywhere close to bespoke software in dealing with the needs of in-house legal teams.

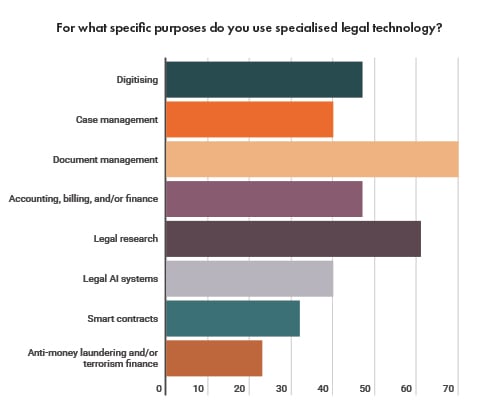

A follow-up question addressed the broad range of purposes of legal tech used by in-house counsel. The majority of respondents noted they used legal tech for document management (70%) and legal research (61%), followed by accounting, billing, and or/ finance (47%), case management (40%) and legal AI systems (40%). We determined that a majority of respondents who employed legal tech used legal tech for at least two purposes, with, surprisingly enough, a small cohort only using legal tech for either document management (4%) or legal research (9%), while a large minority (41%) of respondents used at least four different purposes. Surprisingly, 6% answered that they used legal tech for all recorded purposes.

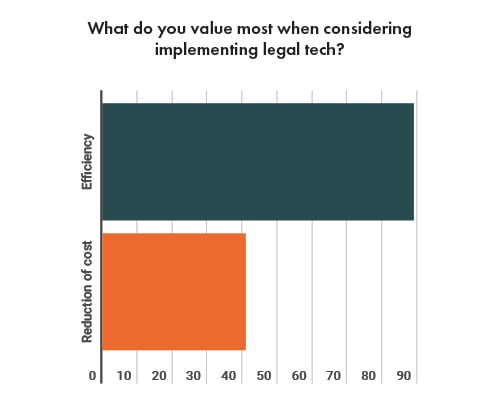

We also asked respondents about what did they value most when considering implementing legal tech. Unsurprisingly, when given a choice to list their priorities, 89% responded that they valued efficiency. This overlapped considerably with respondents who also prioritised reduction of costs, with only 5% of respondents choosing only the value of reduction of costs and no value for increased efficiency. Notably, only one respondent that chose ‘other’ identified a third value that they prioritised over efficiency and reduction of costs, specifically compliance.

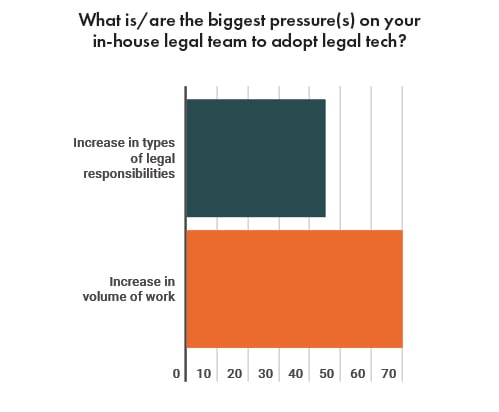

A further question we asked related to the increased pressures on in-house counsel driving the adoption of legal tech. The results matched the expected outcome, with 70% of respondents noting their biggest pressure was an increase in volume of work, followed by 45% seeing an increase in their legal responsibilities. Of particular interest was the fact that a full 35% of respondents only answered their biggest pressure was an increase in volume of work; 32% selected both an increase in types of work and volume of work; and only 14% responded solely that their biggest pressure was an increase in types of work, not volume. A statistically insignificant cohort responded that their biggest pressure was neither of the two main options, but rather due to an increase in regulations (2%) or pressure to integrate into a broader team (1%).

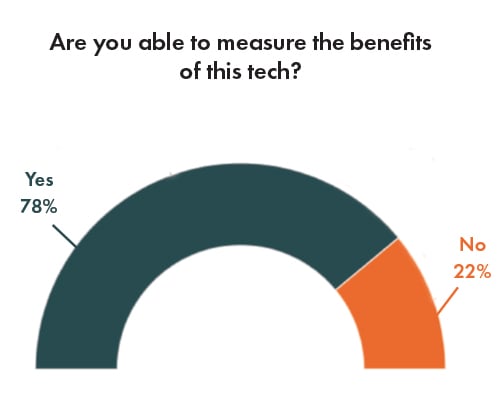

Understanding and measuring the benefits of legal tech is not as easy as it may seem. We have asked our respondents if they can measure the value this technology brings to their jobs. Surprisingly, we had a precise 50-50 ratio.

However, further analysis shows that this 50-50 split in the result is an artefact of the survey, since all respondents that explained they did not use legal tech also answered ‘No’ to whether they were able to measure the benefits of legal tech. This means 36% of respondents must be excluded from this survey question as their null answers skewed the results. A more accurate breakdown of the data revealed that a full 78% of respondents who did implement data tech were able to measure the benefits of legal tech, results that were as surprising as the initial results, primarily because it illustrates how for a majority of in-house teams, legal tech is thankfully subject to Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), were there to be any auditing or examination of the effectiveness of a particular implementation of a type of legal tech.

Additionally, after reviewing qualitative feedback from GCs that did answer affirmatively, this is a group of GCs that are highly enthusiastic about legal tech, as well as excited to detail the ways legal tech has helped their teams. The reasons vary from timesaving to transparency, efficiency and uniformity, and higher productivity.

Some of the GCs offer a different perspective when assessing the value that legal tech brings to their department. They frequently talk about saving time on routine tasks. One GC even said, ‘we’ve had 15% time saved overall’. Another notes, ‘we’ve had time saves, less errors, and more uniformity’. A third GC says, ‘we’ve had lots of time saved through standardisation and cost-reduction in hours spent per contract’.

Even for GCs that have implemented less extensive forms of legal tech such as e-signatures and don’t have tools in place to measure effectiveness express a sense that legal tech has saved them time: ‘it’s just a gut feeling I have that e-signing is faster than the traditional way’.

And for GCs that can’t yet measure the benefits of legal tech in the short-term note that they are still in early stages of implementing new tech. These changes will only be measurable in the medium-to-long-term. Nevertheless, even if there are no measurable metrics in place, lawyers still cannot praising legal tech. As one in-house lawyer affirms, ‘I can’t live without it’.

A two thirds majority consider budgetary constraints as the main challenge to implementing legal technology. However, when digging into additional responses by GCs that answered ‘No’, a more detailed picture emerges, especially as it relates to budgetary constraints and broader corporate culture, the importance of in-house legal teams in the eyes of corporate leadership, and difficulties in communicating the importance of legal tech in response to changing pressures and workloads on in-house legal teams.

Many respondents expressed, as previously mentioned, a feeling that they were caught in the paradox of choice. With, at some times, substantial upfront costs and long-term investment, as one GC noted, ‘tech implementations are complicated and require a lot of support and time to make it successful.’ Other respondents expressed frustration that there was ‘no time and expertise to dive into the topic and set up a project – we’re still operating under the attitude that old solutions will solve everything into looking into new processes first.’

When faced with too many options and too high a cost to implement, some may avoid implementing legal tech until the market becomes consolidated. Some even expressed ignorance of where things currently stood. One GC even said their biggest obstacle was their general lack of knowledge about the available tools at their disposal. For many lawyers, legal tech can feel overwhelming, especially for older GCs that are often disparaged online as the ‘how do I open pdf?’ generation. But legal tech continues to advance at a rapid pace, and even younger generations of lawyers know the experience of stepping away from software for a short period of time to return to an updated UI that looks entirely alien to them.

Other respondents noted a ‘resistance to change on the part of employees’, corporate ‘culture’, or ‘inertia’ in ways of thinking. This conservative attitude towards change may be due to any number of factors, including the adage, ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’, expressed in one response that noted they were operating in a culture that was fixed in ‘the old way of doing things’. This, however, is diametrically opposed to the fact that changes in the amount and extensions of the type of work done by in-house counsel practically demand they have access to the best available tools to properly do their job. This failure to secure ‘organisational buy-in’ was by far the second highest stumbling block to in-house counsel securing funding to access new legal tech.

Another GC expressed this difficulty in demonstrating the importance of adopting legal tech as follows: ‘legal tech requires a lot of work to convince others it is worth the cost, while some more traditional costs are accepted more easily by our organisation.’ Similarly, another GC commented, ‘other client-serving lines are more important than our in-house legal department’, while another lamented ‘value of legal tech is not perceived with the financial decision-makers.’ Generally, in these instances, the biggest hurdle was the perception of cost by leadership, especially if a particular programme or application could not be used universally, even if procuring it was desirable.

One GC’s comments provide a synthesis of the other major hurdles facing GCs wishing to implement legal tech: ‘Overall the biggest difficulty is navigating in an IT world where we have little knowledge, little insight and do not speak the same language. It has been critical to find the right partners in IT who can translate our visions into reality. We pride ourselves on being persuaders, but we needed allies to achieve anything.’

A small number note that there were conflicts between in-house IT security measures and the legal tech available to them, with providers not matching their security standards, or noted that ‘contractual relationships’ already in place made it difficult to implement any automation tools or legal tech generally. Others felt that integration of legal tech with existing platforms or systems was the biggest stumbling block to introducing new legal tech into in-house legal teams.

And in rare cases, respondents felt ‘most existing tools are useless’ or felt the ‘mindsets of our in-house lawyers’ prevented them from implementing legal tech. These responses noted that other lawyers on their team felt more secure using ‘paper-based processes’ or could not set down a clear measure on return of investment in new legal tech. In these cases, some GCs pleaded for buy-in on their teams. As one GC said, ‘there is a need for a paradigm shift. Not many people see the benefits of automated legal tech.’

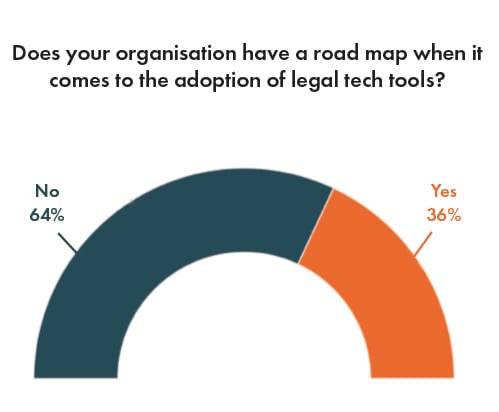

Given companies’ increased interest in legal tech, we have asked our respondents if their companies have clear road maps regarding legal tools.

While the minority, 36%, answered yes, 64% of the respondents affirmed that their corporations do not have a clear plan to adopt the legal tech. As one GC noted, ‘budgetary constraints and other more pressing matters redirect the focus of the team’s attention.’ The main reason behind that seems to primarily a limited budget and small team size; however, increased pressure on legal teams regarding compliance involving sustainability and additional disclosure on ESG also were brought up as limiting the time available for legal teams to construct and adhere to a road map.

There is also a significant number of GC that suggest that even if the time and funding were available, it was simply impracticable for the time being to draft a road map regarding legal technology, mainly because the legal tech space is evolving so fast for that it proved too difficult for the team to establish a medium/long-term plan.

Furthermore, a majority of the respondents state that even though they were interested in implementing legal tech, their companies did not have buy-in regarding the efficiency of legal tech, in part because the corporate side felt the benefits were too hard to measure and they could not see any obvious positive externalities that would be seen outside the legal team.

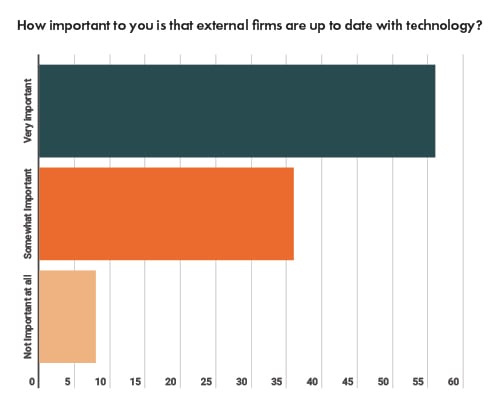

Pressure to embrace change is also reflected in the relationships between in-house departments and external firms. As can be seen with the breakdown in the responses to this question, a majority (92%) believed either it was very important or somewhat important that external firms were up to date with technology. This result is not unexpected – what is unexpected, however, were the answers given by the 8% that did not believe this was important at all.

A common response within the 8% cohort was that external firms must provide sound advice first, and GCs seem not to be concerned with the methodologies by which the advice is delivered, regardless of tech or more traditional practices. Here we see some crossover in the attitudes of corporate towards in-house legal teams: to an outsider, legal teams remain a black box, even to other legal teams. What matters is only the result, and the belief that the result was arrived by a trustworthy method. So this thinking goes, why bother with any new tools that could increase efficiency for an external firm when the efficiencies are not obviously passed on to those requiring external support?

However, among those that responded that it was very important that external law firms are up-to-date with technology, some of the reasons include the need to provide faster and more efficient service to improve cost performance and more user-friendly documents. Here, a majority of GCs clearly understood the benefits that legal tech provided the profession, either due to personal experience or the desire to implement any tools that would help alleviate the strain on an already-overloaded in-house legal team. Additionally, one respondent made an insightful observation about developments in legal tech: ‘external firms should be the one driving innovation, since many in-house teams lack the budget to embrace more cost-intensive and newer type of legal tech.’

For that 36% that felt it was somewhat important that external firms be up-to-date with legal tech, some seemed a bit warier regarding the rapport between external law firms and legal tech. In fact, between those who selected ‘somewhat important’, even though law firms that implement technology into their process are highly competitive in the market, a few respondents expressed caution. One GC stressed the importance of a strong alignment between the technologies adopted by both the client and the external firm. When this alignment is absent, so they said, this introduced a new variable with potentially unexpected results, making it harder to understand the processes, and extending the length and complexity of the overall service.

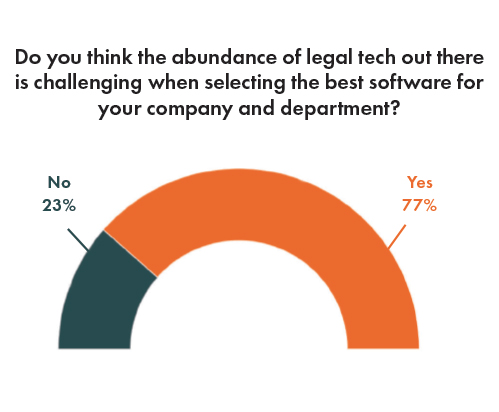

In this ever-changing world, technological advancements are in continuous development. The number of devices and legal tech out there is increasing day after day. And yet, a substantial majority of surveyed QCs believe the extensive choice that legal tech offers nowadays pose several challenges when selecting the best tools for in-house counsel. In short, out of all responses to questions that detailed the major stumbling blocks to investing in new legal tech, the primary factor was the overwhelming number of options of legal tech that have swamped the market.

The data should not, however, be understood to exclude other challenges regarding selecting software, which include corporate attitudes towards change, deprioritising the needs of legal counsel compared to the corporate side of business, stinginess when faced with expensive software options, and difficulties in conveying to corporate management that legal tech was necessary in light of increased volume and type of workload.

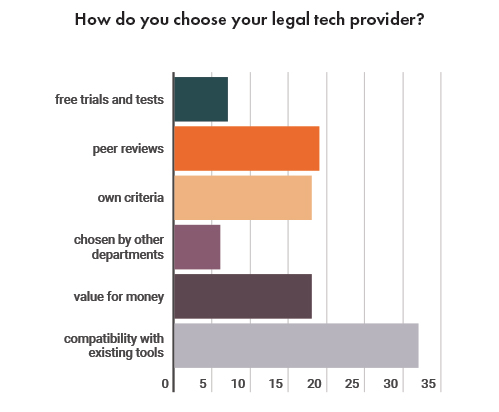

The majority of the respondents affirm that they select the legal tech provider considering the compatibility with software already in place. In-house lawyers look for tools that are compatible with the internal environment and that are easy to use.

Budget plays once again a pivotal role in selecting legal tech. The most common way to proceed among our respondents is by having a direct experience through free trials and tests. Still, the final choice is given by the costs and efficiency of the products.

An interesting finding is, however, that a high percentage of our respondents rely on word of mouth and peer reviews who have had first-hand experience using the given legal tech. Perhaps, knowing that colleagues are happy with their choices can make GCs more confident when choosing since they can concretely see the added value that a specific tool has brought to other legal departments.

Additionally, some in-house legal teams have created their own tailored criteria to make the best choice. As one general counsel suggests, ‘it must be easy to use and intuitive; it must be compatible with our systems already in place.’ Clearly, when one turns to legal tech searches for a solution that is time-saving and quick to learn, especially when the department in question is a larger team, re-training all the members would probably require some time.

However, a minority of the respondents affirmed that the legal department and general counsel have little say regarding selecting the right legal technology. It seems that the final say goes to the IT department. One GC said, ‘the fact that we do not choose is part of the problem.’ While the IT department is probably more familiar when it comes to technology, legal departments being the ones using certain tools on a daily basis would feel way more comfortable being the one selecting the most suitable to respond to their needs. Perhaps having a standardised process in place when selecting legal tech that considers the opinion of both departments could represent a more viable solution.

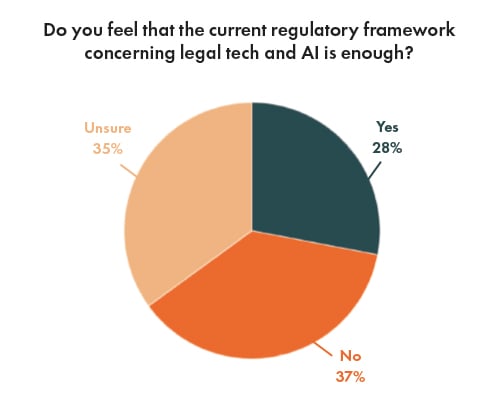

While legal technology is now well established, questions arise regarding its regulatory framework. The data clearly suggest that the majority of our respondents do not think that the current legal framework in place is enough to govern legal tech. Their reasoning for what was missing from current regulatory frameworks was wide-ranging, including ethical guidance for all products developed by big tech, including data collection and AI.

Other GCs mentioned that the legal frameworks in some jurisdictions were inadequate or missing entirely. One GC said, ‘in the Philippines, there are limited regulations on legal technology. For comfort of clients, it will be good to have regulations to ensure that legal tech providers are legitimate and compliant with appropriate regulations.’ This concern, while not prevalent in responses, did indicate the major disparities within different legal frameworks. As another GC expressed their concern over the lack of regulation: ‘What current regulatory framework? If you put legal decisions in the hands of business, you reduce oversight and increase moral hazard.’

Another general trend was the feeling that ‘regulation always falls behind’ technology or that ’technology moves faster than any regulatory framework.’ Frequent responses expressed resignation that no matter how responsive to major issues, since regulatory frameworks were designed post hoc, the fact that regulation was always implemented in reaction to problems meant ‘regulatory frameworks are always late, by its very nature.’

However, some respondents felt that in their specific geographic jurisdictions or industries, some regulatory frameworks may be too onerous. For example, one GC said, ‘if anything, regulations in Europe are sometimes excessive and try to reach into technology spaces that the regulators themselves don’t fully understand.’

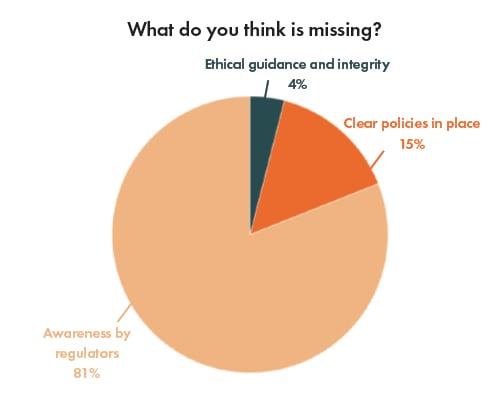

4% of respondents considered ethics to be a missing issue when it comes to the regulatory framework surrounding legal tech. As one GC said, ‘ethics is behaviour-related, and if the intent is not right, technology may not be able to help’. Unfortunately, a related question concerning whether the respondent’s organisation had a robust ethical policy in place regarding legal tech revealed only 39% of respondents could answer in the affirmative.

Additionally, 15% of surveyed GCs believe that there is a need for more precise and transparent policies in place. Respondents call for a more holistic approach – ‘policies appear to be segmented, whereas the use of technology crosses over all aspects of the business.’ However, the biggest issue concerning QCs seems to be concentrated in the regulatory entities not stepping up to provide universal, clear, and appropriate regulations.

Technology develops much faster than legislation, in the general opinion of the 81% of surveyed GCs who said that a regulatory framework should be formulated at the same speed as technology, catching up and pre-empting new developments. ‘Regulators should adopt policies accepting evidence produced by technology.’ Another GCs adds: ‘regulatory framework is often overengineered and focuses on technicalities, lacking common sense and emotional judgement.’

Automation and digitisation of processes certainly help legal departments in daily mansions allowing them to focus on more time-consuming and demanding tasks. Legal tech is evolving faster, providing solutions to several matters that previously fell under the scope of lawyers. However, it is essential to understand the limits of such trends and what the legal department of the future will look like.

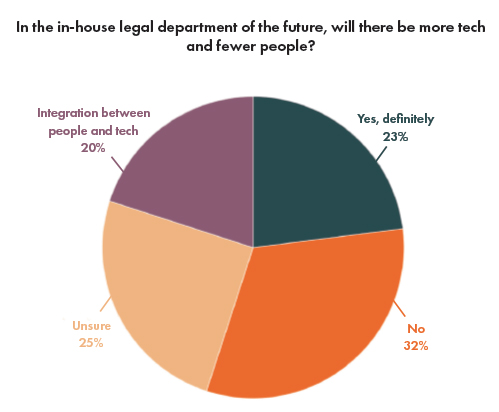

23% of respondents think that the in-house legal departments of the future will definitely have more tech and fewer people. However, in this scenario, GCs seem to believe that there will be a true revolution in the profile of the legal team and the function it will assume within the company. As one respondent suggests, even though the number of people may decrease slightly, there will be the opportunity to operate on a more meticulous selection based on a higher standard to carry out high-quality work. In-house lawyers generally look at this possibility positively, recognising it as an opportunity for lawyers to move up on the value chain, partnering with first-line business teams and providing strategic legal input.

The majority of respondents to this question regarding in-house legal departments of the future believe that legal tech does not mean there will be fewer people in legal departments in response to an increase in reliance on legal tech. A common argument put forward in responses is that ‘automation only eases the pain, but does not necessarily reduce the need for human insight and experience.’

Among GCs surveyed, the human element is considered a key factor that can never be fully removed from in-house counsel, not only because it offers a more creative approach to advice and essential decision-making but also because it allows for building relationships with other departments and business partners, which are crucial in risk management and strategic decision-making process which will enable the business to function and expand. As one GC puts it, ‘my strong belief is that the human factor to the legal professional shall never be replaced by technology.’

A noticeable minority of 20%, however, predicts that the legal department of the future will be a mix between people and tech, with a strong integration between the two. A common pattern in these respondents’ answers is that legal tech and people are not mutually exclusive, but meant to complement each other.

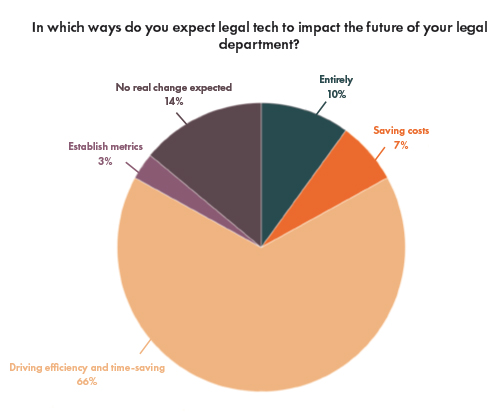

Responses to this question have been varied. Overall, a majority of 86% expect legal tech to bring changes into the legal department of the future. Analysing this data further, we can identify three major categories in the data.

10% of respondents believe legal tech will entirely change the way the legal department operates within the business, touching upon every area: ‘The more you can implement legal tech tools, the more you manage to keep the legal department updated with trends and tasks that the legal department is expected to fulfil. In other words: you need legal tech to keep the legal department competitive in the long run.’

This is contrasted to 7%, who believe that the main change will be reflected in saving costs, while a vocal minority of 3% claim future legal tech will primarily allow establishing clear metrics for KPIs. As one GC puts it: ‘it will allow calculating metrics into the legal analysis, representing a tangible benefit for our internal clients.’

Additionally, the majority of respondents at 66% of all surveyed believe legal tech will positively affect driving efficiency and save time. One of the respondents noted, ‘legal tech will evolve to more suitable and efficient solutions that will manage low risk-high volume repetitive tasks, saving time and resources as well as budget, generating creative and value-added legal work.’

Oddly enough, the remaining 14% did not expect legal tech to bring a noticeable change in the way legal departments operate, especially in the near future. However, given the pace at which legal tech and other major tech tools have developed in even the last two decades and its substantial changes to in-house legal teams currently operate, it’s clear that we’ll soon have a much clearer picture of what the legal department of the future will look like. And unlike this minority of respondents, the majority expect legal tech to help their development every step of the way.

Few would disagree that the global pandemic has led us into a new era. Many call this the ‘new normal’. The term might have been overused, as some media outlets argue, but we cannot dispute that companies around the world are still trying to find their footing with the transformed expectations of their employees, customers, and the societies they contribute to.

The developments that have arisen and which are still arising as the result of the pandemic have prompted corporate legal teams to recognise the need to become significantly more responsive, agile, adaptive, and resilient. In this fast-paced environment, technology has a colossal and indispensable role to play.

Isabel Parker, executive director of the Digital Legal Exchange, warns us, though, that ‘technology is necessary, but it is not enough on its own.’ What she means is that if in-house legal departments intend to become adaptive organisations, they will have to commit to a much more holistic digital transformation.

To conservative and circumspect companies, this may sound like yet another buzzword with little constructive consequences; however, the idea in fact proposes a change in the way companies are structured and the way they work, spanning from their interactions with partners and customers to their relationship with their employees, in order to create a comprehensive digital mindset.

In most cases, the businesses to which in-house lawyers provide support have already embarked on this journey and durably baked digital transformation into their strategies. Isabel Parker observes, ‘there is not a single leading corporation today that has not committed to digital transformation in one way or another.’

Occasionally, however, in-house legal departments struggle to make their voice heard and unfairly carry a reputation of being yet another back-office function whose activities only slow down the business. As a result, when the world’s way of doing business changed, the legal function was often left behind as the last piece of the jigsaw when it came to digitalisation. This was a source of frustration for both sides. But more often than not, businesses have now come to understand and appreciate the far-reaching changes corporate legal teams are undergoing. Although there can still be a disconnection between the two, businesses are now pushing for legal teams to evolve alongside them.

In this evolution lies an excellent opportunity for legal teams to demonstrate their value to the business. However, the disconnection remains as a crucial hurdle. The vast majority, if not almost all, of the general counsels (GCs) report facing challenges in securing a budget for investments in technology. In the light of the current evolution towards digitalisation, this means that despite businesses pushing for the transformation and for a more proactive approach to risks and legal teams’ desire to implement them, there is still a discordance between these aspirations and what is effectively happening on the ground. One way or another, in-house legal departments must find a way to become a different kind of player that works alongside the enterprise to demonstrate tangible value.

Nowadays, GCs openly admit that running a department cost-effectively and coming in under budget is no longer good enough. ‘In-house legal departments provide all sorts of advice to the business side of corporations. As a consequence, GCs need to actively demonstrate this contribution’, says Douwe Groenevelt, Vice President and deputy general counsel at ASML. This is what investment into legal technology needs to achieve.

From a corporate counsel’s point of view, the pressure to start carrying out effective technology policies is also immense. The pace with which the macroeconomic, geopolitical, and regulatory landscape quickly changes and the remits of GCs expand is such that GCs simply do not have the capacity to keep up with the increasing inflow of data without investing in technology.

Isabel Parker explains this bind: ‘I do not know of a corporation that is willing to hire hundreds, maybe thousands of heads to deal with this. Technology is the only way to fight this fire.’

For this purpose, GCs need to have a plan: they must invest in the right type of technology that integrates well with other forms of tech already used across the business. ‘The legal department sees everything, it touches each part of the business and a huge volume of data flows through legal’, explains Parker, ‘so corporate legal teams are very well placed to harness that data and use it to provide insight to drive the business forwards.’

‘It will soon be standard to use technology to spot opportunities for revenue increase, identify which branch of the company has repeated employment investigations or needs to have extensive training on discrimination, detect revenue leakage through specific commercial contract corpus, or track contract renewals’, continues Groenevelt.

These are just a few examples, but what they reveal is that it is this kind of proactive, risk-spotting, risk-preventing, and revenue-generating activities that legal tech need to move towards.

The shift is underway, but it is slow to materialise. The primary reason why this change is so slow for most corporate legal teams, whatever jurisdiction they operate in, is that in most cases, they do not have at hand the benchmarks and data to help them articulate what concrete changes can be implemented.

‘I am a lawyer. I was trained at a Tier 1 firm, and after moving out of practice, was appointed as chief legal innovation officer, a role I held for a number of years. Since leaving the firm in 2020 I have worked extensively with corporate legal departments. This has given me a unique view of the digitisation priorities and challenges facing both private practice and in-house legal teams.

I left private practice to work as the executive director of the Digital Legal Exchange (the Exchange), which is a not-for-profit organisation that works with corporate legal teams to help accelerate their digital transformations. The Exchange is not so much focused on legal operations, although this is obviously an important part of the picture. Rather, the Exchange goes beyond legal operations and legal tech, to help GCs transform their corporate legal department as part of the business’s wider enterprise digital transformation.

The members of the Exchange are global multinationals from all around the world. We offer them a safe space where they can share learnings with other members. The Exchange is supported by a faculty, composed of thinkers and doers from academia, GCs, businesspeople, and technologists. Members share their experiences, explain how they are progressing in their digital journey, and help each other through. It is a very supportive community, allowing senior legal and businesspeople (who despite being great leaders, may struggle to have these conversations) to share with and learn from others.

We have seen a significant shift over the past two years in how legal departments are approaching digital transformation. The GC – and the legal department as a whole – is now much less likely to be perceived as being a business blocker. That once-popular perception has changed. At the Exchange, we recently surveyed our members on their digital maturity. As part of the research process, we asked senior leaders from the corporate legal team and the business to choose, from a list of options, what they saw as the biggest obstacle to change in their organisation. We genuinely expected that the top choice would be that the legal department is not empowered to digitise, or that legal are not perceived as changemakers. But those options were right at the bottom of the list. This confirms that a fundamental change has happened. Corporate legal teams are ready to digitise, and the business wants and expects legal to digitise. Legal leaders now need support in deciding where to go next, and how to use data and technology, combined with a digital mindset, to help the business achieve its goals. I see a huge opportunity in the market for the right kind of advice and support to help GCs deliver more value to the business through digitisation.’

Although a great deal of legal technology was developed with in-house counsel in mind, there are still very few examples where GCs can clearly identify the specific value expected to be generated if they transition to implementing legal tech.

As a consequence, there is little dependable benchmarking data available – there is no clear North Star guiding GCs towards their goal, reliably directing them towards what they should aim for, technology-wise. This makes it even more challenging for them to create a business case that articulates the costs of investing into legal technology.

One major concern voiced is that introducing new forms of technology is likely to give rise to high expenses during its initial implementation, maintenance, and upkeep. Therefore, in the context of business activity, introducing legal tech needs to demonstrate beforehand that it will generate benefits by improving cost or time efficiency in the medium or long term.

However, in addition to finding the appropriate type of technology set-up, there is a prior ‘people challenge’ that needs to be resolved: how do people relate to and interface with the technology? This question is important because people are always the starting point for implementing any new form of technology. It makes no sense to implement a form of technology that does not help accomplish those goals. As American psychologist Abraham Maslow once said, ‘if the only tool you have is a hammer, it is tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail.’ This problem runs in the other direction as well: if the only tool you have is a hammer, no matter how aware you are of what goal needs to be accomplished, you can’t use a hammer as a hacksaw. In essence, you need both the right people and tools to do the job.

Very often, corporations owe their success to attracting and retaining the right people with the right skill sets and mindset in the right roles. Mastering this craft is essential as digital transformation can be a tremendous management challenge.

Consequently, although the digital transformation of in-house legal teams is unavoidable and even desirable, an integrated approach is essential for digital transformation to be implemented correctly. The angle at which GCs consider the approach must embrace their company’s organisational structure, people, and processes before implementation.

‘The first thing GCs must indentify is the problem they are trying to solve by precisely defining the issue and dig deep into what its root cause is. Sometimes, part of a problem stems from the process, culture, documents or something else which technology can easily have a solution for, but is just not clear at the outset,’ explains Roisin Noonan, chief operating officer and co-founder of oneNDA.