PwC discusses recent developments in what is being disputed with HMRC, and also how disputes are progressing

HMRC reports that it typically investigates around 50% of the UK’s 2,000 largest businesses at any one time. Many of those businesses will, at some point, find themselves in dispute with HMRC – and these disputes are, in our experience, increasingly finding their way onto the radar of in-house legal teams.

Although some taxpayers saw HMRC pause their investigative work during the Covid-19 crisis as HMRC redeployed staff to administer the coronavirus job retention scheme, many taxpayers found that HMRC’s enquiries continued unabated. The latest available figures show that HMRC investigative and compliance activities were responsible for around £30.4bn of tax revenues during the year ended 31 March 2021 (compared to £36.9bn in the previous year), notwithstanding Covid-19 difficulties. We have seen HMRC investigative activity steadily edge back towards ‘business as usual’. HMRC told the public accounts committee in December 2021 that they expect work volumes, enquiry timelines and compliance yield to be back on an ‘even keel’ by 2022-23.

The UK tax disputes landscape is constantly evolving – as taxpayers and officers at HMRC adapt to challenges presented by changes in legislation, case law, and technological developments, as well as changes in how HMRC operates. We see development in both what is being disputed with HMRC but also in how disputes are progressing. We reflect on both of these below.

Developments in common areas of dispute

Anti-avoidance

Recent years have seen more and more disputes relating to anti-avoidance rules (of which there are several hundred in UK tax law). Whereas HMRC used to focus their anti-avoidance enquiries on tax planning which they saw as being particularly ‘contrived’, we are finding that HMRC now pursue vigorous anti-avoidance challenges much more routinely.

HMRC frequently table the ‘unallowable purpose’ anti-avoidance rule, which, when it applies, has the effect of disallowing corporation tax deductions arising from borrowings. In common with many UK anti-avoidance rules, the unallowable purpose rule is constructed to test the subjective purposes of the taxpayer in entering into a particular transaction or series of transactions.

Although it is clear that a company entering into borrowing with no meaningful commercial purposes for doing so, and clear tax purposes, can expect to be caught under the unallowable purpose rule, difficulty arises when taxpayers have mixed ‘tax’ and ‘commercial’ main purposes. There have been a string of recent tribunal cases – with more to come, and appeals ongoing – where the tribunals have grappled with, amongst other points, the question of what to do in these circumstances.

Good quality documentation contemporaneous to a transaction is essential in dealing with these sorts of anti-avoidance enquiries. In-house legal teams, with their evidence-based legal mindset, may find that they are able to add value to the thought-process here. To give one example: businesses can sometimes neglect to fully document points that may seem commercially ‘obvious’. Yet capturing the thinking relating to such points in writing can prove useful to help inform HMRC (and, ultimately, the tax tribunal) looking at the matter many years later without inside knowledge of the business context.

Transfer pricing and diverted profits tax

Essentially, the transfer pricing rules apply when a UK company has overpaid expenses or under-received income on transactions with connected parties compared to what would have been paid between unconnected parties acting at arm’s length. The rules require the taxable profit of the UK company to be adjusted to reflect the arm’s length figure. Cross-border loans, royalties, and management charges are typical areas of challenge. HMRC is also active in challenging the allocation of profits to UK branches of overseas companies.

Many taxpayers are, in our experience, finding it increasingly hard to agree arm’s length prices with HMRC that the taxpayer can accept, and may find themselves facing potential double taxation as HMRC looks to price a transaction in one way but an overseas tax authority looks to price the same transaction in a different way.

We continue to see HMRC tabling specialist anti-avoidance rules which seek to identify profits which have been “diverted” from the UK (“DPT rules”) alongside transfer pricing challenges.

We continue to see HMRC tabling specialist anti-avoidance rules which seek to identify profits which have been ‘diverted’ from the UK (‘DPT rules’) alongside transfer pricing challenges. A description of these rules is beyond the scope of this article, but put simply, the DPT rules impose strict time limits such that businesses may be motivated to move towards HMRC’s view on the transfer pricing rather than face the potential risk of higher taxation under the DPT rules.

We are finding that many taxpayers are turning to a ‘mutual agreement procedure’ (‘MAP’) which is a process provided for in international tax treaties designed to eliminate double taxation where two territories seek to tax the same profits. In MAP, HMRC and the overseas tax authority impacted by a particular transaction(s) or situation are required by international law to endeavour to seek a mutual agreement about taxing rights. Over the last six years the total number of cases going through MAP globally has gone up by about 25%. We find that HMRC generally engages actively with MAP. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (‘OECD’), 90% of UK MAP cases eventually reach some level of resolution, making recourse to the UK tax tribunal unnecessary in many cases. However, the MAP process is a lengthy one, with the global average duration being around three years – or a little under two years for UK cases.

Employment taxes

Following recent legislative changes to the off-payroll working rules, PAYE compliance is another area that has received significant recent attention from HMRC. There has been significant activity in the tribunals and courts in relation to questions of employment status – the debate as to whether individuals are employed (and subject to PAYE) or self-employed. So far decisions are split broadly 50:50 (between the taxpayer and HMRC). Whilst themes are beginning to emerge from these cases, the application of status rules remains highly fact-specific. We are also seeing an increase in compliance activity in a number of specific sectors (financial services, oil and gas, public sector) as well as more generally in relation to engagements where contingent workers are providing highly regulated services. Labour shortages in a number of sectors such as logistics and healthcare are exacerbating the challenges faced by clients who are evermore reliant on temporary workers to fill gaps in their employed workforce.

Indirect taxes

Indirect tax disputes also continue to evolve. To give a flavour:

- Technology has been one driver of development. For instance, we have seen disputes arise regarding how aspects of VAT law pre-dating the digital age should be applied to new types of financial services products or operators (eg electronic payment systems).

- The consequences of Brexit have also underpinned some disputes. In particular, disputes have arisen regarding the application of UK VAT to intra-group transactions or arrangements arising as a result of Brexit.

- Another busy area of activity recently has been disputes relating to ‘partial exemption special methods’ (non-standard methods of calculating how much input VAT a business should recover when it makes a mix of VAT-exempt and VAT-rated supplies).

Crypto assets

Tax authorities around the world are grappling with the question of how crypto assets – in their many forms – should be taxed and coming to different conclusions. There are several potential points of difficulty, particularly for UK resident non-domiciled individuals, but also for businesses investing or trading in crypto assets. We expect this to develop over the coming years.

International tax law changes

Significant changes to the taxation of international groups are currently in the pipeline, with a multinational effort involving around 130 countries, led by the OECD. One set of changes (‘Pillar 1’) will have a significant impact on how the digital economy is taxed. Another set of changes (‘Pillar 2’) will make radical changes to existing international tax rules in order to ensure a global minimum level of profit taxation. Many details about the mechanics of the new rules and how they will be administered are yet to be fully worked out. In time, points of contention may very well arise here.

Developments in dealing with HMRC

HMRC’s overall approach to disputes

Many businesses find that HMRC pursues tax enquiries vigorously.

HMRC has a statutory power to require information and documents to assist them with their enquiries. Information requests can be onerous, and it is advisable to engage with HMRC to seek to agree a reasonable information request if possible.

Many disputes will begin with a HMRC information request. HMRC has a statutory power to require information and documents to assist them with their enquiries. Information requests can be onerous, and it is advisable to engage with HMRC to seek to agree a reasonable information request if possible.

Of potential concern to in-house legal teams, recent years have also seen an uptick in HMRC raising serious allegations about taxpayer behavior as a dispute unfolds. There are several reasons for this. Establishing ‘careless’ taxpayer behaviour will enable HMRC to assess to tax years that might otherwise be time-barred. HMRC will also wish to address whether in addition to collecting tax, they should also be charging penalties. We have also seen an increase in Code of Practice 8 and 9 enquiries – which are used by HMRC when they suspect serious taxpayer misconduct.

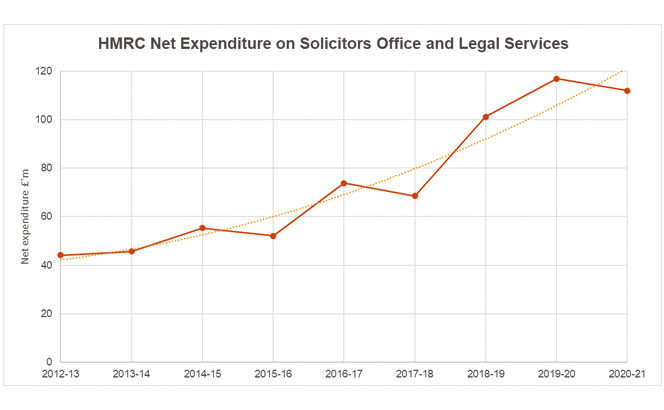

HMRC are not afraid of litigation. It is possible to get some sense of this by looking at the steady recent growth in HMRC’s ‘Solicitors Office and Legal Services’ expenditure (figure 1). HMRC reports a very high litigation success rate (86% success rate in the year ended 31 March 2021). It is worth bearing in mind though that many of the 3,000-5,000 tax appeals that are submitted to the tribunal (upon which this success rate is based) are routine procedural matters, often involving unrepresented taxpayers, where the appeal may well be without any substantive merit. For more sophisticated disputes, it may be a more helpful indication of HMRC’s success rate to look at appeals above the first instance tribunal – typically around 50% to around 80% in a given year.

Settlement

Despite these factors, our experience is that tax disputes can often still be resolved without resorting to litigation. However, it is important to keep in mind that HMRC does not approach settlement like a normal commercial opponent. Any settlement must comply with HMRC’s ‘litigation and settlement strategy’ which, (i) stops HMRC from compromising on black-and-white issues where HMRC thinks it has a greater than 50% chance of success, and (ii) requires there to be a legally-robust basis for settlement in cases which are not black-and-white. In our experience, the ‘litigation and settlement strategy’ is carefully applied to settlement decisions.

We find that it is also possible to usefully engage HMRC in alternative dispute resolution (ADR). HMRC reports that 78% of cases going to ADR during the year ended 31 March 2021 were successfully resolved. However, once again, ADR with HMRC is different to normal commercial ADR: for instance, HMRC insists that the ‘independent’ mediator needs to be one of their specially-trained officers. Our experience is that ADR can be a very useful way of moving to resolution in tax disputes.

Shifting the burden of risk assessment onto taxpayers?

HMRC, like many other tax authorities, faces the challenge of closing the gap between what the government thinks it should be collecting in tax revenues and what it actually collects (the ‘tax gap’). Yet, despite efforts to continue to close the tax gap, the tax gap has remained steady – at around 5-6% of theoretical tax liabilities – since 2015. Preventing the tax gap from lifting up from this historically low level, and trying to shrink it further, remains a significant challenge for HMRC – which also needs to keep its own spending under control.

Part of HMRC’s answer to this has been to seek more forensic ways to identify and assess risks, and HMRC has been relying increasingly on: (i) greater use of technology, and (ii) to place more of the compliance burden on taxpayers. We think this will steadily change the tax disputes landscape over coming years. There are two recent examples of this shifting compliance burden that spring to mind:

- The profit diversion compliance facility (‘PDCF’) – introduced in 2019 – where we have seen continual ongoing activity. Essentially, taxpayers entering into the PDCF undertake their own audit into their tax position (as regards ‘international’ matters such as transfer pricing), and send a comprehensive disclosure to HMRC to show why their historic filing positions have been correct or to propose amendments, in exchange for penalty mitigation. This facility has been supplemented by the use of ‘nudge’ letters that HMRC sends to selected taxpayers to invite them to consider entering into the facility.

- The ‘uncertain tax treatment’ regime, which became law in Finance Act 2022. This will apply to corporation tax, PAYE/NIC and VAT returns filed by certain larger businesses on or after 1 April 2022. This measure obliges businesses to make HMRC aware of particular types of uncertainty in their tax returns.

Conclusions

Anticipating and having a proactive approach to managing tax disputes can make successful resolution much more likely. Disputes are very likely to come to a head many years after the transactions at the heart of the dispute, and this can prove challenging when it comes to assembling the evidence. In practice these challenges can be mitigated by giving some thought to how to evidence positions on transactions that are likely to attract the attention of HMRC at the time of those transactions. HMRC is likely to be concerned to consider in detail the relevant taxpayer ‘behaviours’ and again this can be challenging to evidence many years later. Overall resolution must involve confronting HMRC with a real litigation risk, as HMRC will only reach a resolution on the basis that it is an outcome which is foreseeable in litigation.

Mark Whitehouse

Partner

Tel: +44 (0) 7715 705102

E: m.whitehouse@pwc.com

Peter Johnson

Director

Tel: +44 (0) 7710 036079

E: johnson.r.peter@pwc.com

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP

1 Embankment Place, London, WC2N 6RH

www.pwc.co.uk