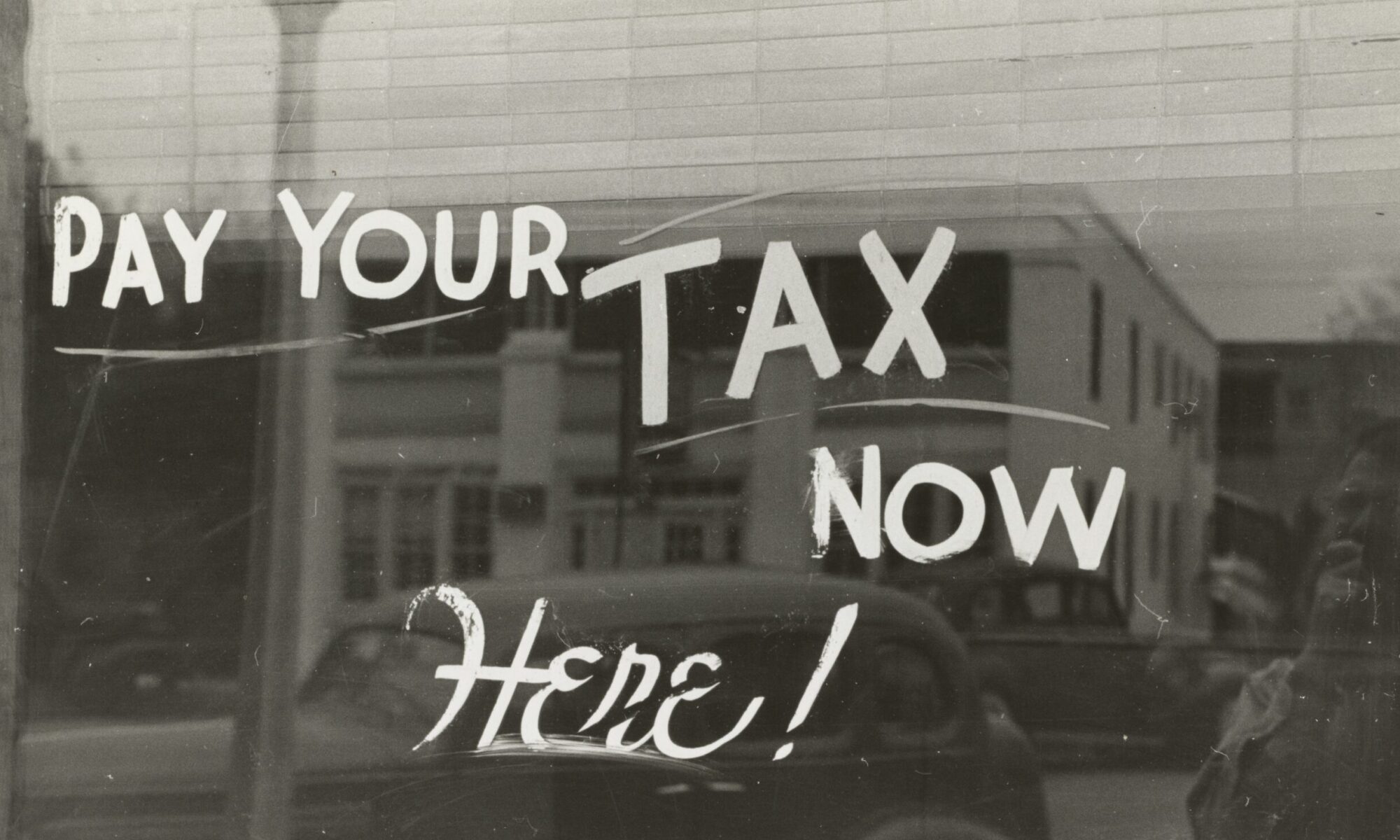

The UK government’s proposed National Insurance reform is more than a tax tweak -it’s a reckoning for law firm partnerships. Stripping away the 7% income tax advantage for equity partners, the reform forces firms and partners to confront whether a structure that’s endured since the 19th century can invest, innovate, or compete in the 21st.

This could prove the catalyst for an industry-wide push to incorporation and throw open the doors for private capital’s advance into the legal sector.

The capital constraint problem

While the law firm partnership model breeds exceptional collegiality and aligns effort to reward, its defining feature – the ‘naked-in, naked-out’ approach – tends to foster chronic underinvestment. Annual full distribution of profit and nominal partner capital serve short-termism and starve firms of the resources and incentives to own assets, upgrade technology, or back new ventures outside the core traditional law practice.

Senior partners are understandably reluctant to fund projects whose returns they’ll never enjoy; junior partners tend to prefer cash today over capital tomorrow. As unincorporated businesses, UK partnerships reinvest only after tax, making every pound of investment costlier than for corporates who don’t pay tax until profits are distributed. If partnerships lose their NI tax advantage, investment becomes even less attractive forcing a hard look at alternatives.

The talent retention problem

Instead of building long-term capital, the partnership model unwittingly rewards exit over retention. Partners can walk away with no penalty for leaving and have no compelling financial reason to stay.

Instead of building long-term capital, the partnership model unwittingly rewards exit over retention

In the past, tight-knit partnerships created bonds of loyalty that constrained exits. Today, market forces, rising pay, and competition make firm-hopping rational – and rampant. Even traditional bastions of partnership stability like Cravath, Wachtell, and Slaughter and May are losing partners, as eye-watering rival pay packages test the model’s limits.

The contrast with private equity structures makes the partnership model’s weaknesses even starker.

Comparison with the PE model

The irony is acute: as data from Edwards Gibson found partner moves in London hit a record 548 in 2024, many departing lawyers are the very advisers counselling private equity clients on long-term value creation and capital structures. PE professionals defer gratification through carried interest, vest over years, and face real financial loss if they leave. Law firm partners, by contrast, face few consequences for jumping ship and have little chance to build compounding wealth within their firm.

Law firm partnership compensation resets annually: value created and consumed each year, with no mechanism to defer gratification or accumulate capital. Private equity structures do the opposite. PE partners build substantial capital accounts with multi-year lockups. Carried interest vests over five to 10 years, tying compensation to long-term fund performance. A PE partner who switches firms forfeits millions in unvested carry. Clawback provisions claw back overpayments if later investments underperform. Law firm partners face no such constraints.

Law firm partners leave because staying costs them the opportunity to earn more elsewhere, with virtually no financial penalty for mobility

PE executives stay because leaving costs them millions. Law firm partners leave because staying costs them the opportunity to earn more elsewhere, with virtually no financial penalty for mobility.

This system institutionalises a free-agent culture in law firms where high earners threaten departure and veto strategic decisions to extract higher rewards – eroding partnership bonds still further and risking management paralysis precisely when long-term collective leadership is essential.

The employee incentive problem

Partnerships also lag on talent incentives. Without true equity, share options, or profit-sharing, they cannot match the career-long upside now common at corporate, ALSP, or PE-backed competitors – who use ‘sweet equity’ and management incentive plans to bind young stars for the long haul.

The NI changes remove a key defence of the status quo

Sophisticated PE investors in law firms understand this instinctively. To exit a law firm investment profitably in three to seven years, they must retain the next generation who’ll replace departing senior partners. Corporate structures offer visible paths to wealth creation and clear exits; partnerships counter with indefinite promotions, opaque process and one-year reward horizons.

The search for solutions

Sceptics say no partnership will accept the short term hit to distributions needed to build capital – why surrender certain income for uncertain gains?

Yet pressure is mounting. The NI changes would remove a key defence of the status quo. Rising partner mobility, technology and AI investment demands that dwarf the capacity of the current model to meet them and relentless PE interest in the legal sector are driving creative solutions.

One model: satellite platforms where firms co-invest with external capital in high-growth practices, offering laterals profit shares, capital growth on exit, and operational independence – without restructuring the core partnership.

Another: minority investments to finance incorporation and reconcile intergenerational equity – particularly attractive for firms with substantial non-legal business lines alongside traditional practice.

And lastly: hybrid models that seek to replicate the capital growth models of PE partnership clients while retaining the partnership structure.

The question is no longer ‘if’ partnerships must evolve, but ‘how’

The partnership model won’t disappear overnight. But its monopoly is ending. Well-capitalised corporate challengers backed by private equity are advancing into the sector with structures designed to retain talent and enable long-term investment. And any move towards more corporate structures will inevitably speed that advance since it makes firms more investible.

The question is no longer ‘if’ partnerships must evolve, but ‘how’ – and whether firms will act proactively or wait for the market to force their hand.

The greatest irony? Lawyers engineering these transformations for clients may finally have to engineer them for themselves.

David Morley is co-founder of Dejonghe & Morley, a consultancy focused on connecting law firms with private capital solutions. He previously served as manging partner and senior partner of legacy Allen & Overy and as managing director and head of Europe for global investment group Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ).

Pinsent Masons saw revenue rise by 4.7% to a new record high of £680m over the year, a result senior partner Andrew Masraf (pictured) described as cause for celebration – while also acknowledging the scope for improvement.

Pinsent Masons saw revenue rise by 4.7% to a new record high of £680m over the year, a result senior partner Andrew Masraf (pictured) described as cause for celebration – while also acknowledging the scope for improvement. National firm Blake Morgan, which has six offices across the UK, boosted PEP by 8% to £349,000 in 2024-25, against a 4.6% increase in revenue; however managing partner Mike Wilson (pictured) said PEP could have been higher still, but for the firm’s strategy of investing profit back into the business.

National firm Blake Morgan, which has six offices across the UK, boosted PEP by 8% to £349,000 in 2024-25, against a 4.6% increase in revenue; however managing partner Mike Wilson (pictured) said PEP could have been higher still, but for the firm’s strategy of investing profit back into the business. At Hogan Lovells, which put in one of the strongest performances of the international firms, with PEP up 9.1% to £2.4m, global corporate and finance head James Doyle (pictured) stressed the importance of adaptability in a fast-changing marketplace.

At Hogan Lovells, which put in one of the strongest performances of the international firms, with PEP up 9.1% to £2.4m, global corporate and finance head James Doyle (pictured) stressed the importance of adaptability in a fast-changing marketplace.