On the international stage, Mexico is known for many things – stunning mountain ranges, distinctive folk art, white sand beaches, and well-exported tradition. Now, another distinction is emerging from the Latin American country: one of entrepreneurship and innovation. According to a survey conducted by the Association for Private Capital Investment in Latin America (LAVCA) in 2019, Mexico accounts for the second-highest proportion of Latin America’s start-ups, second only to Brazil.

With this renown comes investment; money poured from around the world into companies of Mexican origin – so much so that, in 2015, Mexico actually overtook Brazil, becoming the most popular destination for private equity vehicles in Latin America, reaching USD$2.1bn in raised capital, according to the Emerging Market Private Equity Association (EMPEA).

In a funding round this year, card payment start-up Clip raised USD$100m, including a USD$20m investment from Japanese giant SoftBank Group. In 2018, Mexican scooter start-up, Grin, raised a Latin American-record breaking USD$20m in a seed round just months after its founding.

But among the positivity to be found on the ground are worrying signs that Mexico’s hard-fought status as an innovation hub is fading: the government in Mexico has softened its commitment to supporting the country’s start-up scene, and hasn’t been able to make a dent in global innovation rankings, in which it ranks near the bottom of the table out of fellow industrialised countries.

Nevertheless, the demographic case is a strong one (a median age of 27 and 86% mobile phone penetration, according to a 2019 report by the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) Americas Program), and there are highly motivated parties throughout Mexico that are forging ahead, excited to play a role in helping Mexico achieve its massive potential as a nexus of innovation and entrepreneurship in Latin America.

Innovation Actors

Mexico has gradually positioned itself as an innovation hub and global investment destination, but it wasn’t wholly organic. Rather, it has been the result of a push on many fronts: from the federal government, to Mexico’s educational institutions, to the general counsel of industry companies on the ground.

On the government’s part, the Secretariat of Economy established the National Institute of the Entrepreneur (INADEM in Spanish) in 2013, in order to support entrepreneurs and SMEs throughout Mexico, both financially and otherwise. It was the subject of criticism for alleged corruption and inefficiency – and was dissolved in 2019 – but provided direct support to budding entrepreneurs and was initially well funded, with a budget of USD$664m in 2014. The dissolution of INADEM has left a void, and it’s unclear how the new administration plans to enable innovation moving forward. But the economic benefits of realising Mexico’s entrepreneurial potential should be an easy sell for governments.

‘In the beginning, there was a trend, with the government implementing INADEM, in having federal resources used on national investments. At the time, at least 50% of the money invested was put up by INADEM,’ explains Mariana Romero, general counsel at LIV Capital, a leading Mexican private equity fund.

‘You had to compete to get the funding, and fit certain criteria in order to be eligible for the funds. Although it has been terminated now, they are trying other programmes, but they haven’t been so effective. But, the non-financial resources INADEM provided are still being used.’

Azael Capetillo is the director of the INNOVaction GYM – a centre for innovation and entrepreneurship at Mexican university Tecnológico de Monterrey. The centre is located within the university’s school of engineering and, among other things, is focused on accelerating disruption. While the centre caters mainly for students, it is open to enthusiasts and entrepreneurs from the wider community. From that position, Capetillo has seen how the government, both locally and federally, have interacted with the entrepreneurial community in Mexico.

‘The economic office of Monterrey, one of their roles is to increase economic development. They can see through these kinds of actions that their own goals are starting to be accomplished as well. It gets to a point in which this becomes strategic for them, because it progresses their own goals,’ he explains.

‘Sometimes, one of the things the government doesn’t understand is the pains of the industry or entrepreneurs. By working with these kinds of initiatives, they get a close understanding of the problems suffered by the industry and entrepreneurs. Once they understand the problems, they take actions to fix those problems. Most of the time, it’s not that the government doesn’t want to help, it’s that they don’t understand exactly what the problem is.’

This can be of particular concern for start-ups whose business needs have advanced beyond the regulations already in place. For instance, Mexico City-based fintech start-up Credijusto provides asset-backed loans to SMEs in-country.

‘Even though we do structure our loans in a way that you would call traditional lending, the means that we do it from are pointed toward the technological,’ says Ariel A. Lupa Mendlovic, chief legal officer at Credijusto.

‘For example, we are trying to do non-present lending, and that’s where there is a lack of regulation. The regulators are not ready for a company like us approving loans without being in the same room as a client. So, we’re pushing for e-signatures for mortgages, and we are pushing for non-present signatures for IOUs or promissory notes. This is an area of opportunity.’

Mexican Economy

The way that Mexico is governed, together with the economic success that smart regulation and legislation bring, are co-dependent with the well-being of the innovation scene. A healthy Mexican economy will attract more capital, as will inviting regulation – but it is the success of innovative companies in Mexico that feed back into the economy. The result is that every player in the ecosystem plays a significant role in the overall success of the Mexican economy.

‘There are tonnes of opportunities here in Mexico. Mexico is not always seen as that opportunity, because there are worldwide investors that look at other places,’ says Romero.

‘But when you see that there are a lot of good examples in Mexico that we can bring to the world, and put us on the map for investors to see – that’s when you start attracting money to come here.’

Credijusto is a good example of this interconnectedness – in this case, in the fintech sector. Credijusto was born out of the need of SMEs to be able to secure loans at a time when the large, incumbent financial institutions were unwilling to adequately cater to them.

‘Here in Mexico, for instance, there has been a real gap to fill in terms of financial inclusion,’ explains Mendlovic.

‘Banks have been historically fairly conservative in their lending practices – young companies that are creative need a certain amount of financing, but banks would only authorise small amounts, so they were getting left out. But, at a macro level, SMEs are the ones that drive the economy.’

And yet, federal regulations happened to be such that a start-up like Credijusto would be a viable proposition.

‘The gap was easy to fill for Credijusto and similar companies, because regulation in Mexico has been fairly convenient for non-bank lenders.’

Mexico has gradually positioned itself as an innovation hub and global investment destination.

This is also the case for Carlos Sánchez Almada, director of legal, compliance and public policy at Kuesk, another fintech start-up in Mexico offering small loans made available via mobile, facilitated by advances in AI and machine learning, which allow funding decisions to be made in minutes.

‘We are very grateful to the Mexican government because they have given us the opportunity to develop as a new business model, not only by supporting our new concept, but also by allowing us to share our good practices in order to receive their recommendations and apply them to our projects,’ Sánchez explains.

‘Presenting the company and the business model to the authorities is one of my activities, and it is maybe the one I enjoy the most because Kueski has become a high-impact company in Mexico. This is due to the high need for credit accessibility in our country’s population.’

Monterrey, the site of Capetillo’s INNOVaction GYM, is a renowned hub for innovation in Mexico. The reason behind that is another illustration of the interface between business and government, and the roles each play in developing the economy. Initiatives such as Nuevo León 4.0 (Nuevo León being the state in which Monterrey sits) was introduced to modernise the state, long known for its traditional manufacturing and production industries.

‘Monterrey has been an industrial place for many years – over 100. It was a strategy of the government in those times, and now you can see that industry here is very well known for product manufacturing and efficiency. A few years ago, the Secretary of Economy at the time was a businessman, and he realised that the industry here needed to adopt new technology, and he pushed for the creation of this programme – Nuevo León 4.0,’ explains Capetillo.

‘There has been a strategy behind this – that if we don’t change the industry from being a production industry to a knowledge industry, we are sooner or later going to be displaced by someone else. So there is this strategy of moving into a knowledge industry, creating an industry which is leveraged by the previously established companies who create a demand for these new applications. So it’s not only by chance – there has been a lot of planning in the community.’

Romero, having been in the private equity industry for more than a decade, has had a front row seat to the government’s efforts in this area and has taken note of what has specifically contributed to the growth of investment into Mexico. Of particular importance was the recent decision to allow Mexican pension fund managers to begin spending into a broader set of investments than was originally allowed (since the creation of the Mexican retirement fund regime in the 1990s, these pension funds were limited to investments in public debt and foreign currencies). Now, as the Mexican economy has become increasingly sophisticated, regulations have delimited these funds accordingly.

‘Ten years ago, that was unmentionable,’ she explains. ‘Mexican funds had a lot of money and it was just sitting there, and would only be invested in places where there wasn’t much risk, but also not much in the way of returns.’

Education

The aforementioned demographic advantage held by Mexico also means its educational institutions are a critical cog in the machine. According to a 2018 white paper by Mexican industry advocate Entrada Group, Mexico graduates more engineering and technology students on an annual basis than the United States.

‘What the universities have done is to push for knowledge in these areas. Now, it’s a common topic to have blockchain, artificial intelligence, data analysts, cybersecurity and additive manufacturing,’ explains Capetillo.

‘Regulation in Mexico has been fairly convenient for non-bank lenders.’

‘In Monterrey, we have four main universities, which are in the top ten universities in Mexico. Two of our projects, Nuevo León 4.0 and MIT REAP, have joined the universities in pushing for this knowledge and these skills. You have students come in for workshops in Monterrey and then another in other universities and so on. Universities have tried to democratise knowledge and skills in these new technologies.’

Nuevo León 4.0 is a collective effort between the state’s universities, business community and government to maximise output from the longstanding manufacturing centre. MIT REAP – short for Regional Entrepreneurship Acceleration Program – is an innovation accelerator initiated by the eponymous United States university, which isolates regions with great potential for innovation and establishes partnerships with their local communities – particularly their educational institutions – in order to share knowledge across borders. It admits up to eight regions into the programme annually – Monterrey joining in 2018 with Tecnológico de Monterrey as a key stakeholder.

Investing With Mentorship

An indispensable part of the global innovation economy are private equity venture capital funds. Aspiring innovators, with ideas they believe have commercial value, have few options when looking for funding given the chasm between early-stage business propositions and the thresholds and preparation required to embark upon an IPO. Private equity and venture capital firms serve as a facilitator, connecting innovators with sources of cash.

Romero is undoubtedly a reflection of the bullish attitude those GC spoke with towards the role Mexico has to play in the global investment economy, and her enthusiasm for Mexico’s potential and LIV Capital’s ability to realise it is palpable. She joined the company in 2013 as its first in-house legal counsel, at a time when few other funds were considering establishing their own legal team.

‘At the beginning, many firms saw inside counsel as just a cost, and they’d rather hire outside counsel to look after their fund. But I thought that was a mistake: you need a lawyer, and you never know what’s going to happen and you want to save costs by not hiring someone in-house and outsourcing everything to your external lawyer, but he or she does not know the whole story. They don’t know the history of the fund or the portfolio companies. How can an external person be familiarised with the whole structure of the fund?’ she says.

‘Now, I see many fund managers have their own in-house counsel and legal team. You’ll always need support – in-house counsel can’t be all hands-on with everything that happens in the fund; for instance, you might have labour claims or criminal claims – but you need someone to have the ability to collaborate and create a structure in the fund where everything works.’

Starting up the legal function

If the proliferation of in-house counsel within equity funds has been slow to become commonplace, then it’s been even rarer for the high-growth companies they count amongst their portfolio – especially those on the start-up end of the spectrum.

Credijusto, for example, hired Mendlovic as a dedicated legal director at a relatively early stage – and he can see problems arising from a time where there was no legal department within the company. So Credijusto is certainly better off for it, he contends.

‘Our contracts were a mess, and no one in the company could collect on their contracts because they weren’t feasible to litigate. So I came in on a clean slate, and convinced the CEOs that at the core of what we’re doing is selling contracts so it’s very important to have a strong legal team,’ says Mendlovic.

‘We were also wanting to secure VC funding and investments from banks so, on that side, we get all of our advice externally and we were advised well. But, on the other side of the business, that was abandoned to third parties, and external lawyers generally don’t have a deep knowledge of the company, which will always lead to some messes needing to be cleaned.’

‘I like to think of myself as a problem-solving lawyer, and I need to think outside of the box.’

And here again, there is an illustration of how the many ingredients of Mexico’s start-up world connect.

‘You are starting to see a trend – which I’ve been pushing from my side – to have our portfolio companies have their own legal counsel, at the company level,’ says Romero. ‘But it’s often thought that the lawyers of the funds would also be posing as the lawyers of the companies they’ve invested in. Imagine that. How many portfolio companies do you think we have? If I was acting as internal counsel for each of those companies, I wouldn’t have time for anything,’ she says.

‘So, what I have started doing in the past four years is, of the companies we invest in, I make sure they bring in someone. It doesn’t have to be someone that is experienced, because I would be mentoring her or him, and I can be in constant communication with them. We try to differentiate from many other private equity funds. For us, it’s not just money. It’s intelligent money. We’re bringing in the money to grow the business, but we are also helping them – from the business side – to make sure their business is running well on the legal as well as the financial side, so that when an investor eventually comes over, the company has everything they need.’

While ‘fast growth’ might not inspire thoughts of management overly concerned with legal, Mendlovic has found that being the in-house adviser for a start-up has been an experience like no other.

‘Being in a fairly small company – we’re still 260 employees – the environment is actually pretty horizontal. Members of the management team, the CEOs and the founders and the investors walk around through the office and there’s always an element of “Hey, Ariel – we need X. Can we do Y to get it?” And I get interesting questions. I like to think of myself as a problem-solving lawyer, and I need to think outside of the box. It’s pretty interesting to get different members of our team join the compliance perspective with the more aggressive sale perspective to find the perfect solution.’

This aligns with Sánchez’s experience at Kueski.

‘One of the benefits of advising a younger company is the opportunity of establishing the legal foundations from the very beginning,’ he says.

‘As a young, growing company, Kueski faces challenges every day but we do not consider them as problems, but opportunities to learn and become stronger in our determination to be an honourable leading enterprise which can set the example to other start-ups in Mexico.’

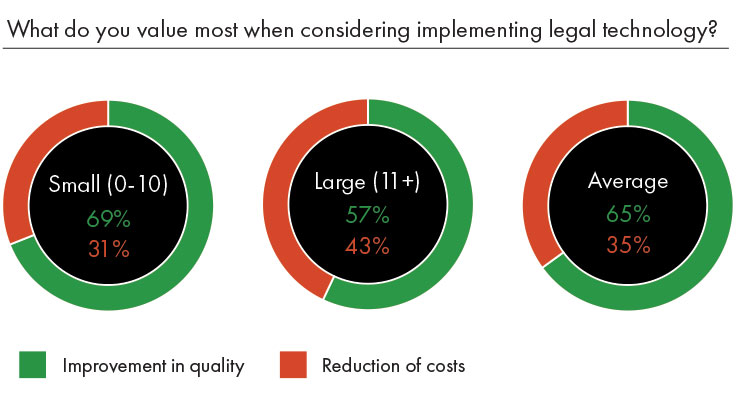

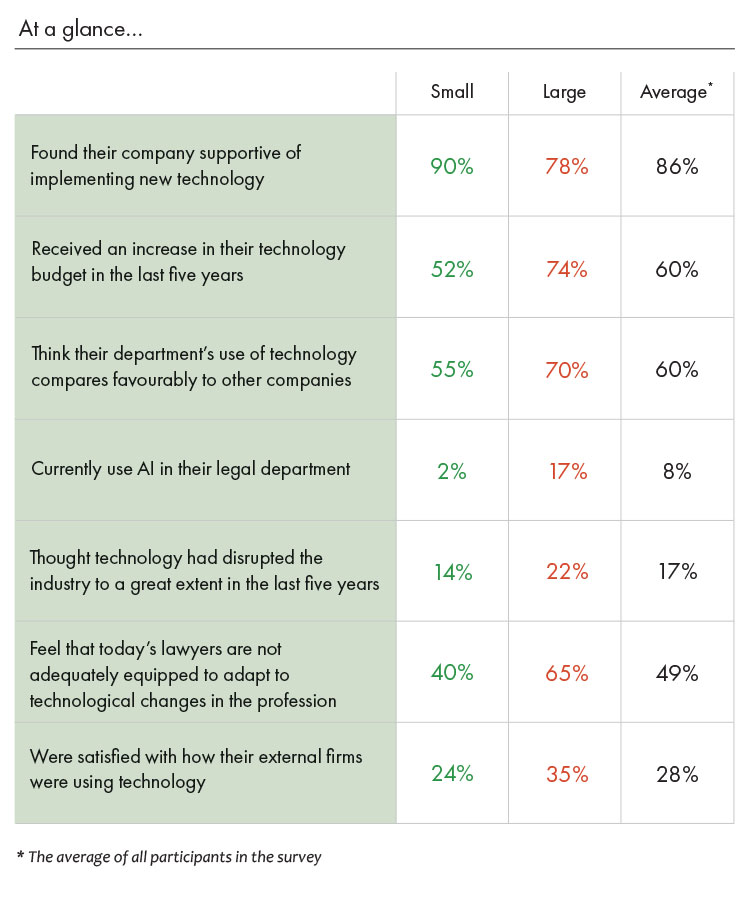

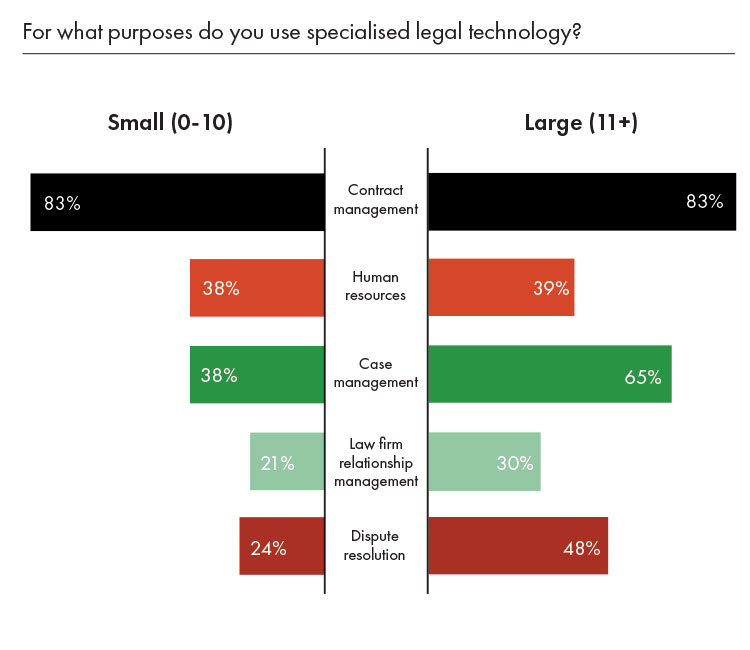

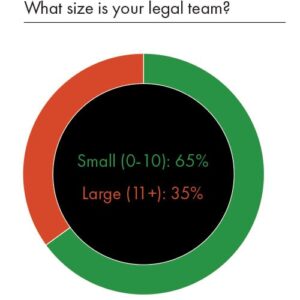

In-house legal teams come in all shapes and sizes: some companies will have small teams, preferring instead to outsource the bulk of their work to external firms, while others have internal legal departments that would outnumber many major law firms. For the purposes of the research that underpinned this report, a small legal team is classified as one with ten or fewer members, while a large legal team is one with more than ten members.

In-house legal teams come in all shapes and sizes: some companies will have small teams, preferring instead to outsource the bulk of their work to external firms, while others have internal legal departments that would outnumber many major law firms. For the purposes of the research that underpinned this report, a small legal team is classified as one with ten or fewer members, while a large legal team is one with more than ten members.