There are certain privileges held by those looking to take on a general counsel role in today’s world. Thanks to the information age, even those outside a suitor organization are able to easily discover facts and figures about their prospective company, and can access a wide range of materials to help them prepare for a new position. General counsel and would-be general counsel now have the troves of knowledge gathered by generations past at their fingertips.

Things weren’t always so easy.

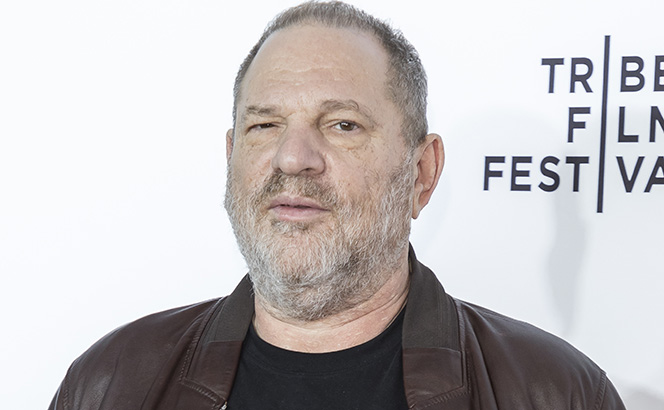

‘I knew nothing. It’s kind of funny. I had been an appellate and supreme court litigator, I had been in government and had run a big office – so I had management experience. But I hadn’t spent one hour working for GE, not one hour. I met Jack Welch [former chairman and CEO], he interviewed me for 30 minutes and offered me the job. The company had 340,000 employees; I had not met one,’ recalls Ben Heineman of his appointment as general counsel of GE in 1987.

‘Welch didn’t know what he wanted. He knew that he wanted to reshape the legal function, but he didn’t know exactly what that meant. When he offered me the job, I said, “I don’t know anything about GE, I’m not a business lawyer.” And he said, “Well, you’ll figure it out.” I was truly driving the car and changing the wheels at the same time.’

To the wise professional, the perspectives of those general counsel whose careers stretch back beyond the current state of things offer more than historical fascination: they are a rich source of insight into how the role of the general counsel has transformed over years past, how it will transform in the years to come, and how the general counsel coming into the role today can best ensure their success in advising their businesses.

Wealth of experience

We talked to those battle-tested, long-serving GCs about their experiences making the transition: the war stories from getting established within the business to reflections on what might be done differently if given the chance.

The best heads are better than one

On arriving at GE, Heineman set about surrounding himself with ‘the best’:

‘I knew one really important thing. I knew I had to get great people – I had done that all my life. I hired great people very fast and Welch supported them. The first person I hired was one of the leading tax lawyers in the country. He made a huge difference and was beloved by the business people. I then hired a world-class and very famous litigator; a very famous person to lead environmental safety. What Welch liked was the fact that I was bringing a ton of new talent into the company. I was the first person to actually hire people from the outside on a consistent basis, I basically blew up the legal organization and over the first five or six years, it was transformed. And that was critical to my credibility – it wasn’t me, it was my super-talented partners.’

In contrast, after more than 20 years in-house with DuPont, Tom Sager went into the general counsel role in 2008 with his eyes open – not least with regard to the company’s extensive litigation docket, having spent over a decade as chief litigation counsel. But, like Heineman, he talks of the benefits of leveraging fresh perspectives in order to have a transformative impact. One particular case from the late 1990s and early 2000s springs to his mind as a striking example, not only of leveraging the best talent, but also ensuring that talent is diverse.

‘We were dealing with lead paint litigation. We had a fairly strong team of defendants: we had ARCO [Atlantic Richfield Co], Lead Industries Association, and Sherwin-Williams. These were big players, and there was a mindset that said “We’re going to fight all these cases to the death”. I said to myself, “Well, that’s all well and good, but you’re only going to win so many, and then you’re going to be in more of a hurt because there’ll be some cases in which you’ll lose, and then, as we say in the US, the price of poker goes up,”’ recalls Sager.

‘So we got a team of diverse, talented people – Dennis Archer, who was the president of the ABA, mayor of Detroit, and a world-class guy; Benjamin Hooks, who was a civil rights icon; and several others. We got in a room and I said, “We don’t want to roll over, but how do we go about addressing the problem?” They came up with this idea of creating the Children’s Health Forum, which was designed to do three things: drive education with respect to inner-city families whose children were possibly exposed to the lead paint poisoning, remediation and then medical testing. Dr Hooks, at the age of 78, agreed to chair the Forum and he traveled the country to engage with primarily black inner-city mayors.’

DuPont was eventually dropped from the lawsuit in Rhode Island.

Learning to listen

Hiring talent is only as effective as the partnerships that allow organizations to capitalize on that pool and, like any good partnership, they should flow in all directions around the business. When Mark Ohringer began his first tenure as general counsel at Heller Financial, Inc in 2000, he believes he missed an opportunity to build relationships with those around him.

‘I should have gone on a bit more of a listening tour and gone to the heads of the business. I had already been in the department when I became GC and I probably thought that I knew what everybody wanted. But I should have put myself on their calendar for half an hour and checked that,’ explains Ohringer.

‘It puts a line in the sand: “New sheriff in town, I want to understand what you want as my client, and let’s have a discussion – tell me anything, how can I help you, and how can I be a good colleague?” I think I would have been more formal about going around business people and the people running the corporate functions. Particularly listening and not talking so much.’

Blowing the comfort zone wide open

The general counsel’s office has evolved from a silo to an intersection of cross-departmental collaboration, responsible for leading teams that include an assortment of internal and external specialists. The role has come down from the ivory tower to the corporate thoroughfare, meaning the leap from specialist to generalist is all the more critical. While cultivating a network of experts remains important, the GC must be able to view matters through a broad lens, regardless of background (and comfort zone), as Sager learnt the hard way at DuPont.

‘I turned down a commercial lawyer assignment that didn’t thrill me at the time, and that was probably one of the biggest mistakes I made,’ he says.

‘I did not spend time enough to know how the businesses are challenged and how they meet their profit objectives, and everything that they must deal with. Had I known that and taken that assignment outside my comfort area, it would have made me even an better general counsel.’

Private Practice Perspective: As much as things change, they stay the same

Jonathan Polkes, co-chair of Weil’s global litigation department and a member of the firm’s management committee, has been recognized as one of the top securities and white-collar defense attorneys in the United States. In this Private Practice Perspective, Polkes unpacks the qualities and traits that, in his experience, have been a hallmark of standout GCs, while also considering what constitutes a true business partner in the context of in-house counsel.

While the role of the general counsel has clearly evolved and expanded in recent years, the core qualities, traits and competencies for those who succeed and thrive in these roles has not. In collaborating with leaders of large global financial institutions and public companies over the last three decades, I have had the opportunity to partner with GCs of different leadership styles, experience levels and professional backgrounds. But, irrespective of their differences, all had their own distinct point of view while being highly agile and responsive to change. All could leverage advice from their teams and outside counsel to distil complex legal issues into plain language for the primary stakeholders at their organizations. And all prioritized building the best, brightest and most diverse teams possible.

I routinely work with general counsel who are under the gun – whether their companies are ensnared in a cross-border investigation or facing nasty securities fraud allegations. When the stakes are high, it is more important than ever that the GC has a firm sense of the value of the case to the company – financially and reputationally. These are not times to vacillate or second guess. At the same time, if there are key developments that suddenly change the complexion of the case and its value proposition, the stellar GCs I’ve had the privilege to work with always respond to that change immediately and effectively.

Given the scope and complexities of these cases, our firm works with GCs to make the underlying issues as succinct and digestible as possible. The business decision makers at sophisticated global companies need things distilled for them. What will this cost? What are the reputational risks? What are the best and worst options for resolution? How will this impact our brand or our operations six, 12, 18 months down the road? At Weil, we partner with GCs to sift through the immense amount of data and cut through all the noise to isolate the essential issues at the heart of the case. Having that clarity of mind and keen business judgement has always defined the best GCs.

In today’s marketplace, the battle for the best talent has grown into full-fledged warfare. Again, the GCs I’ve worked with embrace competition. They always surround themselves with a diverse team of people who are at least as smart as they are. There has been positive culture dialogue and developments surrounding diversity, certainly, over the past three decades – but needing the best people will always be key. And hiring the best people means hiring and retaining diverse talent.

As strategic business partners with our GC clients, Weil aims to mirror all these attributes. And while the role of outside counsel has changed along with that of the GC, we know that the qualities and standards governing our practice, client service and teamwork will never change.

Jonathan Polkes Co-Chair of Global Litigation Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP

He did, however, accept another stretch assignment, which stood him in good stead over the years.

‘After four years of being a labor and employment lawyer, I was asked to be a lobbyist for DuPont in Washington, which was as foreign as it could possibly be. That assignment was painful at first but, over time I began to appreciate the value of being a representative of the corporation, because it exposed me to the issues that were challenging DuPont broadly, how one prepares to advance legislation or defeat it, and how to build coalitions and networks.’

Counseling the counsel

The experienced general counsel we spoke to have put in the years to develop the comprehensive scope and alliance-building skills necessary to succeed at leading the legal organization in top corporations. So what advice can older hands give to those navigating less familiar waters for the first time?

The right counsel for the job

‘The most important question is: does your skillset align with the needs of the corporation? I was a litigator, and we had a lot of serious litigation, so that led to my appointment. If your corporation is in a growth mode, then they’re probably looking for somebody who’s more versed in the core area of M&A deals and cross-border transactions,’ observes Sager.

‘General counsel will always have to put out the fires – that’s a given – and you need to be skilled in that. But increasingly, the general counsel is viewed as a part of a senior leadership team, and with that comes responsibilities – some way beyond knowing how to defend a litigation or handle an investigation or a crisis.’

Whatever skillset or background today’s GCs bring to the table, they will quickly discover that the role has evolved beyond individual expertise into a broad-based, proactive and strategic position. And although there is no fixed blueprint for becoming GC, let alone succeeding in the position, experienced past and present holders of the title agreed that there are a set of qualities that aspiring legal leaders should possess.

Communication skills

General counsel must bridge the gap between the legal and business mindsets, and also overcome any outmoded preconceptions that business colleagues might harbor about the dreaded ‘department of no’.

‘I was truly driving the car and changing the wheels at the same time.’

‘Lawyers tend to talk too much and write too much, and for business you need to be very succinct. Nobody has the same attention span that they used to – they’re used to these little sound bites on their mobile phones, and you can’t hand a business person a 25-page brief,’ explains Mark Ohringer, general counsel at Jones Lang LaSalle since 2003.

Horizon spotting

‘We used to sponsor a NASCAR driver by the name of Jeff Gordon, and my CEO Chad Holliday showed us this picture of Gordon in his car, circling and making a turn in one of these races,’ says Sager.

‘“You have to help us anticipate the curves”, Holliday used to say. They might create an opportunity or risk for the corporation, and you can’t be effective if you’re not thinking along those lines.’

Most of the general counsel we spoke to agreed that GCs need to be particularly attuned to all kinds of change, including societal and political developments that are ostensibly unrelated to business.

‘There are new kinds of risks that never existed before,’ says Ohringer. ‘Cyber risk, social media – none of that existed when I started practicing 25 years ago, and now they’re enormous.’

GCs need to be particularly attuned to all kinds of change.

A keen eye trained on the distant horizon will assist not only in managing and mitigating risk, but in planning for worst-case scenarios. GCs can be useful in bringing together the various siloes within an organization to design future crisis response, and ensure coordination between internal and external specialist resources.

‘A terrorism situation, a natural disaster, all these things keep happening. Are we ready as a company? Because if we’re not, there can be really bad legal risks, and that’s why the lawyers have a ticket to think about it. Those kinds of things didn’t used to happen so much and now they’re pretty much commonplace, so you need to make your response ordinary course of business. Nobody should be surprised when these things happen anymore,’ Ohringer explains.

Strength of character

When times get tough, fault lines often appear around the general counsel if they are not properly negotiating what Ben Heineman has called the ‘partner-guardian tension’.

Much has been written in recent years of the importance of effective partnership between organizations and their lawyers. The office of the general counsel has matured from the in-house approximation of the partner-associate-business ‘client’ model, to a deeper and more strategic enmeshment in the fabric of the business. So far, so value-add. But GCs must have the independence of mind to walk a line.

‘You have to have that partnering relationship with the CEO and the business leaders, but at the end of the day, your real job is being guardian of the company, which requires a certain amount of independence,’ explains Heineman. ‘There’s a certain tension between these two roles: if you are just a nay-sayer – just a guardian, protecting and risk averse – you’ll be excluded from meetings, you won’t be part of the team, and you won’t be able to play a business as well as legal role. But if you’re an inveterate yay-sayer and just do what they tell you to do, you’re going to get indicted.’

‘If you’re an inveterate yay-sayer and just do what they tell you to do, you’re going to get indicted.’

These are blunt words from a veteran GC, but necessary ones.

‘I think, sometimes, this idea that the lawyer should be part of the strategy may have actually gone a little too far,’ echoes Ohringer. ‘Big companies have had some terrible things go wrong; and how come the legal function didn’t help? It may have been too protective of the company.’

‘As all this evolves, lawyers have to not get sucked into the business too much. They need to understand it in order to do their jobs, but there’s still a need to maintain some independence. I always said I should not be the last one at the bar at night after business meetings – these are not my friends and I have to keep a little separate, because if they do something wrong, I represent the company, not them.’

We look next to today’s crop of newer recruits, and examine how they are rising to the challenges faced by the modern general counsel – and what advice they give to those currently eying the job.