Israel has been, and continues to be, a highly desired market for foreigners to invest in. 2017 saw total Israeli exit transactions of approximately $23 billion, including Mobileye for $15.3bn. Though this is down in terms of volume, it is up in terms of value. This is perhaps an indicator that the Israeli market is maturing and that Israeli entrepreneurs are now more able and willing to grow their companies to the point of significant market share, or past an IPO, prior to exit, as opposed to historical trends of those entrepreneurs looking for a quick exit. Continue reading “Foreign investment in Israel”

NRF loses veteran litigator Eastwood to Mayer Brown in further exit as Reed Smith scoops Pinsents’ Middle East head

Mayer Brown and Reed Smith are continuing their recent expansion trajectories, this time at the expenses of Norton Rose Fulbright (NRF)’s London base and Pinsent Masons’ Middle East operations.

NRF saw the exit of one of its most senior London partners as veteran litigator Sam Eastwood headed for the door after three decades to join Mayer Brown. Continue reading “NRF loses veteran litigator Eastwood to Mayer Brown in further exit as Reed Smith scoops Pinsents’ Middle East head”

Deal watch: HFW acts for Greek government on major state sell-off while US firms score heavyweight mandates

In a deal of major national significance, Holman Fenwick Willan (HFW) and Clifford Chance (CC) have advised the Greek state on the €535m privatisation of its gas network. Meanwhile US leaders Kirkland & Ellis, Weil Gotshal & Manges and Jones Day have also acted on substantial buyouts recently.

The sale of the natural gas transmission system operator, DESFA, is part of Greece’s wider strategy of disposing assets to reduce the country’s debt following the financial crisis. The deal implies a total equity value for DESFA of €810m. Continue reading “Deal watch: HFW acts for Greek government on major state sell-off while US firms score heavyweight mandates”

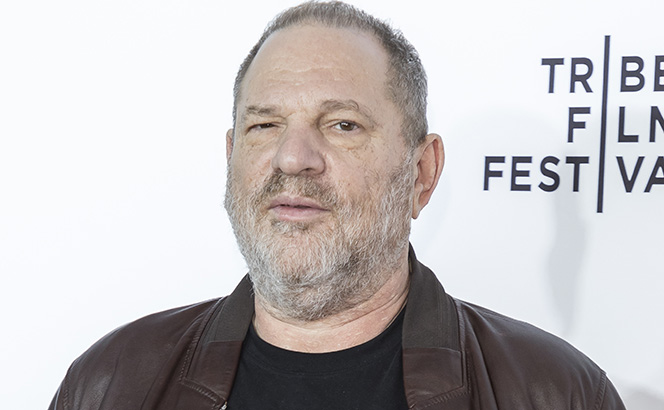

#MeToo: MPs slam ‘utterly shameful’ inaction on sexual harassment amid calls for an overhaul of NDAs

A parliamentary select committee has blasted employers and regulators for failing to tackle sexual harassment in the workplace and has called for a clamp-down on the use of non-disclosure agreements (NDAs).

The report by the Women and Equalities Committee on sexual harassment in the workplace published today (25 July) is the culmination of an enquiry launched by MPs in the wake of the #MeToo movement that saw the legal profession’s handling of these situations thrust into the spotlight. Continue reading “#MeToo: MPs slam ‘utterly shameful’ inaction on sexual harassment amid calls for an overhaul of NDAs”

Foreword: Barry Wolf

At Weil, we consider ourselves strategic business partners with our clients – you, the general counsel of large public companies, complex financial institutions and sophisticated private equity firms. In my 35 years practicing and running the firm at Weil, I have seen how tremendously the role of general counsel has evolved and expanded over the past four decades. The legal head of a large organization has always borne the heavy burden of ensuring excellence across their legal departments, management and oversight of all risk mitigation systems, and the development and enforcement of quality corporate governance protocols. But today, we are seeing the fusing of all these responsibilities with the business operations and over-arching corporate strategy. Senior lawyers are expected to be providing business judgement as well as legal judgement.

As a result, I’ve seen the role that we play, as outside counsel to our clients, also shift in that time. As we heard from the in-house lawyers who contributed to this report, there is now an interconnectedness of all business, strategic and legal issues. We carefully analyze legal issues for our clients, but we do not stop there. We supply commercial and business judgement, to help them answer that key question: ‘What should I do here?’ This makes for a dynamic time to be a lawyer, whether you are in-house or outside counsel.

I’ve also felt, more and more in recent years, that the legal leaders in organizations are expected to be responsible and responsive corporate citizens – far beyond the walls of their organization. We have always embraced that at our law firm, but now employees want their leaders to have an active voice on global issues that are impacting their lives – whether in or outside of the workplace. Again, this provides in-house legal teams and corporate management with a real opportunity to engage in a dialogue with their employees and address important cultural and social issues. It can forge and strengthen the bonds of loyalty so vital to an organization’s success.

There will always be new and changing developments to the practice of law and the issues facing in-house teams. What will never change is the need for bright, driven, collegial, diverse and adaptive lawyers to fill these roles. As the world and businesses grow more complex, the in-house leaders, including those profiled in these pages, will have the opportunity to be business as well as legal strategists. It’s exciting times, and I congratulate all of the dynamic and diverse GCs featured in this issue.

Barry Wolf Executive Partner Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP

Tony West, Chief Legal Officer, Uber

I was one of these people who actually did not have a burning desire to become a lawyer. I was much more interested in public service, politics and policy, and I decided that I needed to go to law school so that I could have a marketable skill if a career in public service didn’t work out. But I discovered, to my surprise, that I really enjoyed the law.

I spent the first part of my legal career as a federal prosecutor. After I left that, I ended up spending several years at a law firm where I learned civil litigation. But I always harbored my love for public service and so when President Obama asked me to join his administration, it was a great honor and a privilege to go back to the Justice Department, first as the head of the Civil Division (which is the largest litigating division at the DOJ, with 1,000 lawyers) and then eventually as the third most senior official in the Department.

When I was coming to the close of my time at the DOJ, I knew a few things. I did not intend to remain in the administration to the very end, and I didn’t necessarily want to go back to a law firm. When you’re the Associate Attorney General of the United States, that’s sort of like being the general counsel of the Justice Department. There’s a set of skills and talents which are transferable to being the GC of a large company.

It’s always helpful to have the perspective of the regulators and to understand what they are trying to accomplish. I think oftentimes we find ourselves operating in stereotypes – if you’re in the public sector you have stereotypes of what you think people in the private sector are like, and vice versa. The experience of being on both sides of that line helped me to appreciate that there’s actually a lot of common ground and a real opportunity for people to reach resolutions that are mutually acceptable, but also to work together in a very collaborative way.

The other thing that was helpful was the experience of managing a large organization with many competing interests and, of course, one filled with lawyers. Being able to figure out how I could be most effective in that environment was extremely helpful when I became the general counsel of PepsiCo. And it’s extremely helpful to me now.

The learning curve at PepsiCo was steep, because I had never been in-house before. I had never been a business partner before. That made it critical that I immediately learned the business as best I could – and that’s exactly what I did. I got very granular, talking to business leaders and business colleagues throughout the company.

There’s no substitute for really learning the business, because your value as a lawyer to your business colleagues is enhanced when you really understand the problems they’re dealing with from their point of view. I think it helps you to come up with more creative solutions, and it helps you to give them advice that is actionable and useful.

That’s exactly what I’m doing at Uber – spending a lot of time with my team, the business teams, and spending a lot of time in the field, in markets like Latin America, which is currently our fastest growing market.

The greatest thing about Uber is that this is a company that is like no other. It offers a job or an economic opportunity to more people around the world than any other company on the planet. That is an amazing reach. This business model is so robust, it is so widespread, it has its reach in so many corners of the world, that you become very aware of the public trust that you have – because so many people rely on your platform to either move themselves or their loved ones from A to B and so many people rely on this platform for economic opportunity. So many cities are increasingly relying on the data we have on our platform to help them make better planning decisions so they can become more sustainable places for their citizens to live and work. To be a part of that, to be an engine for that, and to be able to advise on the development of that is extraordinarily exciting.

The other thing that’s really extraordinary about this place if you’re a lawyer, is that you work on issues which, if they get themselves into the court system, almost inevitably become issues of first impression. It means you are forging the law, you are on the cutting edge of creating a legal framework for the gig economy – and for a lawyer, that is an incredibly exciting environment to work in.

One of the things that being at a company like Uber forces you to do is to look at the existing paradigm, the existing legal framework, and then think very creatively and innovatively about ways in which you can address the basic values that that framework is trying to protect and do it in a way that actually fits the reality of how people live and work.

For instance, something that’s at the heart of our business model is the independent contractor model – the question of whether Uber is an employer of drivers or whether those drivers are independent contractors. We’re all operating within a framework that was constructed for very good reason over a century ago, and the question – can we preserve the values that framework is seeking to protect, creating a safety net for individuals when they change jobs or decide to move to a work environment that allows them to value their time and their freedom and liberty and flexibility? – can’t be a false choice between flexibility and having an array of benefits or a safety net that will help people retire with dignity, that will protect them when they get sick. Being a part of really pushing that conversation and creating a new legal paradigm that fits today’s reality and today’s economy – being a lawyer at Uber gives you the opportunity to play a very significant role in that.

One of the things I’m most proud of here at Uber is that we were able to resolve what was our biggest private litigation, the Waymo case, so quickly. I think the fact that we were able to resolve that and the way we were able to do it not only demonstrates that we’re serious about turning the page on the way things operated and that we are serious about striking a new tone, but I think it also creates a path to greater collaboration and co-operation with a company that, just a month ago, was a big adversary.

One of the things I’m most proud of at PepsiCo is that we were able to really enhance our position as an ethical business leader while I was there. I’m excited about bringing some of the innovations and approaches that we developed when it comes to compliance, ethical leadership and integrity in the way that we do business from PepsiCo to Uber.

The other thing I’m proud about at PepsiCo is the work we did to enhance diversity in the legal profession. We were able to create incredibly diverse legal teams, because we know that when we bring diverse voices around the decision-making table we can make better business decisions, and I look forward to doing that here.

Particularly in technology companies, like this one, where there’s a premium placed on innovation and on speed, the general counsel role is extremely important. I always focus on the ‘counsel’ part. You cannot come to this role and think of yourself as a lawyer. You have to think of yourself as a counselor and partner who can provide legal advice – but also general counsel to your business partner on legal, business, policy and reputational issues.

I don’t think Dara [Khosrowshahi, CEO at Uber] has ever asked me what’s the law on this, or what’s the law on that. He needs to know my judgement and my approach – and that will be informed by my legal judgement, but what he’s looking for is counsel. That is really what I want all of my lawyers in the legal department to begin to think of themselves as – they are business partners who need to give sound counsel to their business colleagues – and if someone is interested in this role, that’s what they have to prepare themselves to do.

Tom Johnson, General Counsel, Federal Communications Commission

I have always been attracted to public service. A number of my colleagues from my time at Gibson Dunn had gone on to serve as solicitors general in state attorneys general’s offices. Those offices provide unparalleled opportunities, such as the chance to argue appeals and challenge areas in which the federal government has exceeded its powers and placed onerous regulatory requirements on the state. So I was very grateful to have been offered the opportunity to work in the West Virginia solicitor general’s office.

In 2017, I became the general counsel of the FCC. I’m primarily responsible for two components – reviewing Commission rules and orders to ensure they are legally sustainable, and defending those actions in court. I also oversee units that deal with fraud and bankruptcy issues, as well as various internal issues like employment matters. In West Virginia, I supervised four or five attorneys at any given time. Now, I oversee a team of more than 70 lawyers, so I’ve had to focus a lot more on learning how best to allocate my time, how best to delegate, and who are the best people to delegate various issues to.

I came into this position with very much a generalist understanding of administrative law and appellate law. And while I had done some communications work in the past, I definitely rely on staff to brief me on particular areas that require a lot of technical or substantive expertise. But one benefit of bringing a generalist perspective is that I’m in a good place to understand what sorts of questions and issues a judge might have and how they will approach reviewing a particular Commission action, and to ensure that what we’re doing is likely to be upheld in court.

I think the first few weeks in the role were probably the most challenging – you really inherit a whole world when you come into a federal agency, and so the early days are occupied with learning new names, learning people’s responsibilities, and learning the various practices and processes at the agency. Once you’ve had some time to reflect on that, then you can start to think constructively about what’s working, what’s not working, what you’d like to change and what you’d like to improve.

Along with one of the new deputies that came in with me, I spent a lot of our early weeks scheduling meetings, both with different team leaders from the office of the general counsel, as well as with our stakeholders in the agency. That meant they could put a face to a name and we could show that we could learn about what they were doing and also how we could improve the relationships between the office of the general counsel and other offices within the agency. We have tried to create an open door policy so that folks who have pressing issues can come to us directly. That’s the way in which we tried to immerse and integrate ourselves early on.

Oftentimes, the perception of a general counsel, whether it be in a federal agency or in the private sector, is of someone who has the unfortunate responsibility to say no a lot of the time, and that person takes on a reputation for impeding progress within an organization. I think that a GC certainly needs to be aware of the legal prohibitions, and there may be times when they need to say no, but that person should also think of themselves as a facilitator, to help further the agency’s mission consistent with the law. In the gray areas, the general counsel needs to be clear in articulating what the various legal risks are, but to also help the organization achieve its objectives.

Unlike in the private sector, we don’t have the option of using outside counsel to represent us for particularly challenging or time-intensive matters. That’s part of the challenge, but it’s also part of what makes the job exciting. At the FCC, we have our own in-house litigation division, so that’s different from some agencies, who rely exclusively on the Department of Justice to handle the cases that end up winding their way to court. It allows us to be more holistic in how we approach legal problems, evaluating at the outset whether the rules or the orders that we’re adopting are easily sustainable – with one eye towards what sort of arguments we can make if they are challenged in court.

Another consideration is that attorneys in private practice divide their time amongst multiple clients, but when you work for the government, your client is ultimately the people. This means there’s much more focus on how the positions you’re taking will serve the public interest as a whole – not only in the case in front of you, but also long after you’ve left office.

One benefit of being in a management position working for the state is that it allowed me to be a lot more entrepreneurial. The attorney general was very receptive to attorneys coming up with ideas of how best to further the state’s interest, even if that meant initiating a law suit in federal court to challenge federal rules as unlawful. Because we had a lot of authority and ability to think of creative solutions, there was also a lot of trying to stay on top of legal and political developments in the news and trying to ascertain how we could best further the agenda of helping the people of the state when the federal government passed a rule that could adversely affect their interests.

Another thing a general counsel in federal government can do is focus on institutional issues that will affect the agency – not only in your time – but also in the future. There are some perennial issues that agencies encounter, like: how do we fund our programs and activities, how do we manage documents and data collection preservation? While these are not issues that take up a majority of my time, they are mission critical, so they are opportunities to think through how to set processes and procedures in place that will be consistent with both our legal obligations but also introduce efficiencies into the organization so that future people who come into my position will benefit.

Looking ahead, the increasing complexity of the modern administrative state will mean that general counsel are going to need to be much more interdisciplinary and also conscious of what their counterparts are doing in other agencies. There are a lot of areas where agencies share jurisdiction, where jurisdictions overlap, where consultation is required by law, or where review is necessary before action can be taken. So it’s increasingly important for general counsel to know what those requirements are, who to call at other agencies to get things done, and who the different stakeholders in the process are.

I also think that keeping on top of technological developments is going to be important. The tools that lawyers are using to do their work are constantly evolving, and the role that social media is playing in government messaging is evolving. And in the private sector, with respect to a lot of the entities we regulate, oftentimes the law may not evolve quickly enough to catch up with technological change. These factors are going to present challenges for lawyers to exercise good judgement in determining how existing laws apply to new technological developments and unforeseen situations. The answer in a lot of these cases will be for the federal government to get out of the way of competition and technological developments that are occurring.

There are two pieces of advice that I would like to give other attorneys.

The first is to be flexible in your career path and open to taking risks when a new opportunity comes your way that excites you. I would never have believed it if you had told me a few years ago that I would be deputy solicitor general of West Virginia, and then general counsel of the FCC, but those opportunities have been both a really enjoyable and rewarding experience, and I would encourage other lawyers to do the same.

The second is that it’s really important to cultivate a reputation for integrity and excellence among your peers starting in law school, because those are the people who one day are going to be in a position to speak to your character and your qualifications if the right opportunity comes along.

Stacy Cozad, General Counsel, Spirit AeroSystems

I think there are a lot of lawyers who have a vision of their career when they first start out, but I was not one of them. I didn’t have a plan to become a general counsel, for example. I simply had the good fortune of meeting the right people at the right time and being open to new challenges. My career path has been about the people that I’ve met who have been my advocates and promoters along the way.

I started my career clerking for a judge who is now the US Senate Majority Whip, John Cornyn. He was someone who really valued his staff’s views and insights, and I wanted to be a courtroom lawyer in front of judges who respected me like the judge I worked for did.

But as I said, my path has been about the people I’ve met along the way. It was for its people that I chose to go to Southwest Airlines to be head of litigation. Southwest is an airline that was founded by a lawyer (Herb Kelleher) who made it his mission to ‘democratize the skies’ in the US – to make it possible for everybody to be able to fly. I was fortunate to have been a part of that for over nine years.

The opportunity at Spirit AeroSystems arose, and again it was due to a prior relationship – somebody I worked for in the past recommended me for the job. Spirit was an opportunity to go from an airline to an air structures manufacturer, getting to be a part of a global business with operations in the UK, France and Malaysia, as well as multiple places in the US.

To come to the general counsel role was a big leap for me, and I was fortunate that in the past I had had a very diverse litigation practice that included, for example, corporate governance issues. Also, in private practice, I had worked as part of the defence team for CEO Kenneth Lay in the Enron litigation in the US, which was, of course, a huge changer of basic corporate governance tenets. At Southwest Airlines, I also got to do a lot of regulatory oversight, corporate investigations and the integration of another airline. All of those things were very helpful for prepping me for being GC, at least in terms of the legal role.

But the biggest leap was the business, and going from an airline, which is essentially customer service, to aerospace and defence manufacturing. That was an enormous learning curve, and remains so. I read everything I could get my hands on before I got here about the industry. There were people within Spirit who I reached out to, to learn what we do and how we do it – for example, taking tours of our manufacturing facilities, walking through the plant floor to see what we make and talking to the people who make these aircraft structures, and also spending time digging in with our corporate controller to learn the very different financial and accounting aspects of a manufacturing business versus an airline.

At the time, the best advice I could have given myself is that I don’t have to learn everything today. In the first few months I was here, I felt that I needed to know everything right away and, in all of the work that I did trying to learn as much as I could, I neglected myself. Have a plan for all the learning that you need to do, but make sure you are making time to sleep. Taking the job meant moving my whole family to a new city. I have children, and I did not sufficiently take into account what that transition would be like for us on a personal level. So I think you have to learn that you don’t have to know it all on the first day. Have your plan and make sure you take care of yourself in the process.

The things that I find most rewarding really centre around people that I’ve had the privilege to lead who have gone on to do tremendous things in their careers or try new challenges. I’ve been most proud of the teams that I’ve put together and the smart people on those teams. On the flip side of that, the most challenging moments have been ‘people moments’ – learning how to adapt and work with people who don’t operate with the same core principles and values as I do. It’s really tough to stand on an island alone, but sometimes you have to do it. At Spirit, we’ve just begun the journey of shifting our culture and our values, so those most challenging moments are learning that not everybody yet has bought into those core values and principles, and having to learn how to influence people to get on board.

Fortunately, the single most valuable thing that contributed to my view of leadership was the leadership program that I went through at Southwest Airlines. I was actually the first lawyer to go through it, and it taught me the importance of having a core set of principles and values and instilling them in people across your business, so that everybody is operating from the same set of guidelines in making their business decisions. I think that’s no different from understanding your company’s risk appetite or strategy – if you don’t know what those things are, you don’t know the framework for the decisions that you need to make.

Since I’ve been here, I have expanded my leadership to our compliance team, I have taken on our global contracts team, and I will be taking on the information security team – the chief information security officer we’ve just hired will report to me. As you see the general counsel role expanding to really influence business strategy, I think it will also expand to have more leadership of some of these non-legal areas because of the interconnectedness of them. Most businesses will benefit from a general counsel who has some oversight and an intimate involvement with all those other foundational elements of the business.

There are other things throughout my career that helped prepare me for my job at Spirit. I had stepped into my role at Southwest Airlines at a time when e-discovery was just coming into effect, and so I was able to be pretty innovative in the leadership there in getting us to a sophisticated state in our litigation practice. Coming to Spirit, I would say I’m bringing innovation, but it’s not new things; all of the things that I did at Southwest I’m bringing here now. Spirit just hadn’t had the opportunity or the need to get current in the same way.

For example, I have started doing something that’s pretty common in our industry, but wasn’t common at Spirit, which is unbundling the legal services. We’re not hiring law firms for every aspect of a litigation matter or due diligence, for instance, because there are non-traditional legal service providers that you can couple with a law firm, which are a lot more cost-effective. We’re bringing in things like technology-assisted review and artificial intelligence, which started in e-discovery and now we’re expanding over into revamping our contracts management. If you can use tools like AI to help you gather more information about your state of compliance and contracts management, then you’re going to equip your lawyers to deliver much more efficient and practical legal advice.

I think this represents a broader trend. I’m surprised we still have as many very large law firms as we have. At Spirit, we do hire large multinational law firms, but I am personally a fan of smaller practices that I think deliver better value for the client, depending on the matter. There are times when you need a firm with a global presence, but I continue to believe that we’re going to see more boutique-style law firms that really understand their clients’ need for practical advice that furthers their business goal. And I really think we’re going to see more service providers in this area where we’ve unbundled various things. There are companies that are not law firms, but which have lawyers you can use on a project basis with your law firm partners on matters – sort of an ‘à la carte’ menu where you can piece together what you need. More law firms will, I hope, start to see the benefit of partnering with those non-traditional service providers.

Audrey Lee, General Counsel, Starz

I think that coming from an in-house role to the GC position is an easier transition than going directly from being a partner in a law firm, because the role is so different. Being the outside lawyer, you don’t have the perspective of the consigliere. Although folks can obviously be successful that way, I think that’s a bigger jump.

I would have loved to work in more industry sectors! But I think the unique thing about entertainment is that once you’ve started down that road, if you try to interview outside of the industry, there’s a lot of scepticism. People wonder why – it’s a desirable, sexy industry and people are more often trying to break into it rather than break out of it.

I have loved the job since I’ve been here because of the variety that it presents. One day I’m working on an FCC filing, the next day it’s a shareholder litigation, the next day it’s a big contract with our biggest licensing partner. I also like the opportunity to really feel like you are making an impact at the highest levels on the direction of the company – that’s something I hadn’t experienced before I became general counsel.

Just as I was starting the job, Starz went through something that was pretty unprecedented for the company – it was dropped from one of its distributors. Going through that entailed a lot of regulatory and political work, as well as transactional negotiations that was a huge challenge for me and for the rest of the company. Coming out of it with a deal was something that I’m proud we were able to achieve.

The general counsel position is in essence a generalist role. You’re not just the transactional lawyer, you’re also looking at litigation, regulatory issues, political issues, all of those things, and I don’t know that it’s very easy to get that experience prior to taking on the role. I was primarily a transactional lawyer – IP and entertainment – so I had done the corporate M&A stuff, the securities stuff, and also done IP and entertainment licensing and distribution, but I hadn’t done litigation. I had been involved, but I wasn’t the one leading litigation. I hadn’t done production work to the extent that I’m now responsible for. The best preparation you can do is to get involved in a lot of different things and try to get the broadest experience as you can. Even as a transactional lawyer, I would support litigation, which was useful experience.

When I was at Sony, I had been doing a certain type of entertainment work; I was good at it and it was my area of expertise. But after five plus years of doing that, I obviously wasn’t learning as much – it was like the back of my hand. I was looking around at other opportunities within the company and somebody advised me to consider another area in order to get experience I didn’t have. My response was: ‘Yeah, I’d be willing to try that, but I wouldn’t want to give up what I have now.’ I wanted to take on new things, but I didn’t want to let go of what I had.

The person wisely said: ‘You already know that stuff, it’s on your résumé, nobody can take that away from you. Everybody will know that you are an expert in that stuff after having done it for five or six years, so it’s ok for you to let that go in order to take on other responsibilities – and it will be better for your career growth.’ He really encouraged me to let go and make room for new things, and I thought that was really great advice. As soon as you’ve mastered something, it’s time to move on and get some other experience.

I’ve always told my teams, whether it was at Sony Pictures, Lionsgate or at Starz, that we need to advise the business not just from a legal standpoint, but from a strategic standpoint. When you think about a contract, the parts that are purely legal are all pretty boilerplate and a very small part. Our role is to bring up all of the concerning business points that might come up in a contract: does it really make sense for this agreement to be non-exclusive, does that fit with our strategy? Does it make sense for this to be a long-term deal? Maybe we want more flexibility to do this other thing next year? It’s really advising on the business strategy and what you see coming up in the future to help them achieve their business goals. I feel like I’ve been doing that since I started being a business lawyer and this is just a little bit more official now that I am general counsel.

I’d like to think that there was a move towards having more women in the GC role. I don’t know if I would say that mentoring and nurturing of diverse attorneys is increasing in the entertainment industry, but the Weinstein scandal may bring on some change. Maybe it will make women feel a little bit more emboldened to speak out about the need for diversity in the workplace – they can now point to that, so it doesn’t have to be so personal. Companies are letting go of people for all sorts of reasons related to the Weinstein issue, and it’s exciting to see that change is happening. I don’t know if it’s going to be sustainable, but there’s definitely more awareness and sensitivity than there ever has been before.

Eric Dale, Chief Legal Officer, Nielsen

Working at a dotcom was the first time I really got inside a business and became part of the leadership team – and obviously the dotcom era was a moment in time that was incredibly instructive for people to understand what a bubble looks like.

Some things were very different to my role now at Nielsen, and some things were very similar. It was more of a start-up environment, the legal department was much smaller, and it was largely a US-driven company. Nielsen is a much larger department, and it’s a much larger, global company. That said, the fundamentals are pretty consistent across the board. You’re trying to help grow the company, do so in an ethical, compliant way, and you’re continuing to try and be creative as you address issues.

In legal services, I think there are certain consistencies and evolutions. Technology is very different now to when I was in-house last time, and I think technology will likely be very different five, ten, 15 years from now.

If you’re in a small organization, the opportunity to have a broader role is greater. As an organization grows, things tend to get a little more siloed and remits tend to narrow a bit. But on the other hand, CEOs for the last decade or so have really begun to see that general counsel with certain skillsets and temperaments can add value in areas beyond the traditional scope of work assigned to a GC or CLO.

One thing I’m seeing in other companies – and have experienced myself here at Nielsen – is that the remit of the general counsel tends to be expanding. For instance, I joined Nielsen as the CLO and had responsibility for the legal department. Since then, my remit has expanded to include security, corporate social responsibility, government relations and public policy, as well as enterprise risk management. The job is becoming broader (which I happen to like) and I think boards and CEOs are recognizing that a GC may bring a host of skills that extend beyond simply running a legal department.

I don’t know exactly what I expected when I became general counsel at Nielsen, but it is different. In a law firm, you’ve got a large portfolio of clients, but once you go inside, you have one client. It can be a large, complicated client, which Nielsen is – with around 45,000 people spread across the globe in more than 100 countries, and multiple businesses in various legal and regulatory regimes.

You get much more involved in the business of the company in a leadership role. The kinds of things that cross your desk are incredibly diverse, and as diverse as private practice was, this is much more so.

Another key difference is that as outside counsel you try really hard to develop close relationships with your clients, but there’s a certain distance that you’re never going to be able to overcome, regardless of how good you are. Ultimately, you give advice and then the client takes that advice as an input and makes a business decision. When you’re inside, you give that same advice, but you live with that decision. You can’t walk away, so you have to own it from a perspective that’s not simply about what the law is, but what the company’s risk analysis is, what the business’s objectives are, and a whole host of other factors that you need to synthesize.

The hierarchy of a corporate structure is much more defined than the hierarchy of a partnership. That colors a lot of how I think about my own behaviors. For instance, when I speak to people, I know that often they are hearing the chief legal officer, they’re not necessarily just hearing a colleague. So trying to think not only about the matter that I’m discussing with them, but also their frame of reference, is a little different than in the past.

In a law firm, they have partners and associates. I initially analogized my position at Nielsen as me being a partner and the rest of the department being associates. I quickly learned that this was a poor analogy! A better analogy is more along the lines of being a managing partner in a law firm and that there are a lot of other partners, as well as associates. At Nielsen we have really smart, accomplished, independent lawyers who have great judgement and can run with matters often with little-to-no input from me – they know how to reach out to me, and I view my role as largely to help them do their jobs and clear obstacles and work through issues when they want a sounding board. That’s a very different dynamic than the frame of mind I came in with.

I read everything when I took the job at Nielsen – I read books, I read articles, I talked to people who were current GCs and former GCs, and there were a lot of themes that came out of that research. First of all, you really need to get to know the business. Second, you really need to develop relationships with people that you’re going to be working with, both vertically and horizontally in a matrix organization. Third, you need to recognize that the breadth of the practice is significant. You can’t be an expert in everything, but you have to have a good working knowledge in a lot of areas. I’d encourage people to go as broad as they can in their current position, whether in-house or in law firms, to make sure they really understand the dynamics that exist beyond their specialty.

I’m not sure that the general counsel’s skills are going to be radically different ten years from now. GCs are always going to have to know the business very well to be effective. They’re going to have to develop strong relationships with executives and with business leaders, and developing leadership skills is going to be critically important. Finally, where GCs are going to excel or not is in having great judgement and being able to communicate their thoughts into a rationale for what they’re discussing. Technology and tools will change over time, but those are just ways to do our job – the skills are going to be the constant.

I think in the future, routine work will be technologized and repetitive jobs will go away – and go away could mean offshore, it could mean go to non-traditional legal service providers, but it’ll likely not be done in-house or by law firms.

People use the word innovation a lot these days, and it means a lot of different things. People naturally think of innovation as connected to technology, and a potential value is that you can create data from experience, which can help from a consistency perspective. At Nielsen, we’ve tried different technologies and software from time to time, and we’ve also worked to create and implement processes to help make our work more efficient and more consistent. We’ve created model forms, knowledge management databases, and certain practices and policies which, coupled with training, teach our department and our internal clients how to accomplish their goals in a more streamlined fashion. We’ve also engaged RFPs in select areas, which has helped reduce costs significantly during a time when, as a company, our revenue has grown – which is a big win.

I think, in future, the pendulum will probably swing back and forth about whether legal departments grow or more work is outsourced but, by and large, my guess is that more work will be insourced. I think it’s ultimately more cost effective to have insourced work, and as you start to focus on paying for the highest value work – it comes back to judgement and expertise – you’ll go outside for that if you happen not to have that in-house, and you’ll pay for that. But you won’t pay for the lower-end work. You’ll either take that in or, more likely, you’ll outsource it to third parties who can do it more efficiently than a law firm.

Voices of Experience

There are certain privileges held by those looking to take on a general counsel role in today’s world. Thanks to the information age, even those outside a suitor organization are able to easily discover facts and figures about their prospective company, and can access a wide range of materials to help them prepare for a new position. General counsel and would-be general counsel now have the troves of knowledge gathered by generations past at their fingertips.

Things weren’t always so easy.

‘I knew nothing. It’s kind of funny. I had been an appellate and supreme court litigator, I had been in government and had run a big office – so I had management experience. But I hadn’t spent one hour working for GE, not one hour. I met Jack Welch [former chairman and CEO], he interviewed me for 30 minutes and offered me the job. The company had 340,000 employees; I had not met one,’ recalls Ben Heineman of his appointment as general counsel of GE in 1987.

‘Welch didn’t know what he wanted. He knew that he wanted to reshape the legal function, but he didn’t know exactly what that meant. When he offered me the job, I said, “I don’t know anything about GE, I’m not a business lawyer.” And he said, “Well, you’ll figure it out.” I was truly driving the car and changing the wheels at the same time.’

To the wise professional, the perspectives of those general counsel whose careers stretch back beyond the current state of things offer more than historical fascination: they are a rich source of insight into how the role of the general counsel has transformed over years past, how it will transform in the years to come, and how the general counsel coming into the role today can best ensure their success in advising their businesses.

Wealth of experience

We talked to those battle-tested, long-serving GCs about their experiences making the transition: the war stories from getting established within the business to reflections on what might be done differently if given the chance.

The best heads are better than one

On arriving at GE, Heineman set about surrounding himself with ‘the best’:

‘I knew one really important thing. I knew I had to get great people – I had done that all my life. I hired great people very fast and Welch supported them. The first person I hired was one of the leading tax lawyers in the country. He made a huge difference and was beloved by the business people. I then hired a world-class and very famous litigator; a very famous person to lead environmental safety. What Welch liked was the fact that I was bringing a ton of new talent into the company. I was the first person to actually hire people from the outside on a consistent basis, I basically blew up the legal organization and over the first five or six years, it was transformed. And that was critical to my credibility – it wasn’t me, it was my super-talented partners.’

In contrast, after more than 20 years in-house with DuPont, Tom Sager went into the general counsel role in 2008 with his eyes open – not least with regard to the company’s extensive litigation docket, having spent over a decade as chief litigation counsel. But, like Heineman, he talks of the benefits of leveraging fresh perspectives in order to have a transformative impact. One particular case from the late 1990s and early 2000s springs to his mind as a striking example, not only of leveraging the best talent, but also ensuring that talent is diverse.

‘We were dealing with lead paint litigation. We had a fairly strong team of defendants: we had ARCO [Atlantic Richfield Co], Lead Industries Association, and Sherwin-Williams. These were big players, and there was a mindset that said “We’re going to fight all these cases to the death”. I said to myself, “Well, that’s all well and good, but you’re only going to win so many, and then you’re going to be in more of a hurt because there’ll be some cases in which you’ll lose, and then, as we say in the US, the price of poker goes up,”’ recalls Sager.

‘So we got a team of diverse, talented people – Dennis Archer, who was the president of the ABA, mayor of Detroit, and a world-class guy; Benjamin Hooks, who was a civil rights icon; and several others. We got in a room and I said, “We don’t want to roll over, but how do we go about addressing the problem?” They came up with this idea of creating the Children’s Health Forum, which was designed to do three things: drive education with respect to inner-city families whose children were possibly exposed to the lead paint poisoning, remediation and then medical testing. Dr Hooks, at the age of 78, agreed to chair the Forum and he traveled the country to engage with primarily black inner-city mayors.’

DuPont was eventually dropped from the lawsuit in Rhode Island.

Learning to listen

Hiring talent is only as effective as the partnerships that allow organizations to capitalize on that pool and, like any good partnership, they should flow in all directions around the business. When Mark Ohringer began his first tenure as general counsel at Heller Financial, Inc in 2000, he believes he missed an opportunity to build relationships with those around him.

‘I should have gone on a bit more of a listening tour and gone to the heads of the business. I had already been in the department when I became GC and I probably thought that I knew what everybody wanted. But I should have put myself on their calendar for half an hour and checked that,’ explains Ohringer.

‘It puts a line in the sand: “New sheriff in town, I want to understand what you want as my client, and let’s have a discussion – tell me anything, how can I help you, and how can I be a good colleague?” I think I would have been more formal about going around business people and the people running the corporate functions. Particularly listening and not talking so much.’

Blowing the comfort zone wide open

The general counsel’s office has evolved from a silo to an intersection of cross-departmental collaboration, responsible for leading teams that include an assortment of internal and external specialists. The role has come down from the ivory tower to the corporate thoroughfare, meaning the leap from specialist to generalist is all the more critical. While cultivating a network of experts remains important, the GC must be able to view matters through a broad lens, regardless of background (and comfort zone), as Sager learnt the hard way at DuPont.

‘I turned down a commercial lawyer assignment that didn’t thrill me at the time, and that was probably one of the biggest mistakes I made,’ he says.

‘I did not spend time enough to know how the businesses are challenged and how they meet their profit objectives, and everything that they must deal with. Had I known that and taken that assignment outside my comfort area, it would have made me even an better general counsel.’

Private Practice Perspective: As much as things change, they stay the same

Jonathan Polkes, co-chair of Weil’s global litigation department and a member of the firm’s management committee, has been recognized as one of the top securities and white-collar defense attorneys in the United States. In this Private Practice Perspective, Polkes unpacks the qualities and traits that, in his experience, have been a hallmark of standout GCs, while also considering what constitutes a true business partner in the context of in-house counsel.

While the role of the general counsel has clearly evolved and expanded in recent years, the core qualities, traits and competencies for those who succeed and thrive in these roles has not. In collaborating with leaders of large global financial institutions and public companies over the last three decades, I have had the opportunity to partner with GCs of different leadership styles, experience levels and professional backgrounds. But, irrespective of their differences, all had their own distinct point of view while being highly agile and responsive to change. All could leverage advice from their teams and outside counsel to distil complex legal issues into plain language for the primary stakeholders at their organizations. And all prioritized building the best, brightest and most diverse teams possible.

I routinely work with general counsel who are under the gun – whether their companies are ensnared in a cross-border investigation or facing nasty securities fraud allegations. When the stakes are high, it is more important than ever that the GC has a firm sense of the value of the case to the company – financially and reputationally. These are not times to vacillate or second guess. At the same time, if there are key developments that suddenly change the complexion of the case and its value proposition, the stellar GCs I’ve had the privilege to work with always respond to that change immediately and effectively.

Given the scope and complexities of these cases, our firm works with GCs to make the underlying issues as succinct and digestible as possible. The business decision makers at sophisticated global companies need things distilled for them. What will this cost? What are the reputational risks? What are the best and worst options for resolution? How will this impact our brand or our operations six, 12, 18 months down the road? At Weil, we partner with GCs to sift through the immense amount of data and cut through all the noise to isolate the essential issues at the heart of the case. Having that clarity of mind and keen business judgement has always defined the best GCs.

In today’s marketplace, the battle for the best talent has grown into full-fledged warfare. Again, the GCs I’ve worked with embrace competition. They always surround themselves with a diverse team of people who are at least as smart as they are. There has been positive culture dialogue and developments surrounding diversity, certainly, over the past three decades – but needing the best people will always be key. And hiring the best people means hiring and retaining diverse talent.

As strategic business partners with our GC clients, Weil aims to mirror all these attributes. And while the role of outside counsel has changed along with that of the GC, we know that the qualities and standards governing our practice, client service and teamwork will never change.

Jonathan Polkes Co-Chair of Global Litigation Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP

He did, however, accept another stretch assignment, which stood him in good stead over the years.

‘After four years of being a labor and employment lawyer, I was asked to be a lobbyist for DuPont in Washington, which was as foreign as it could possibly be. That assignment was painful at first but, over time I began to appreciate the value of being a representative of the corporation, because it exposed me to the issues that were challenging DuPont broadly, how one prepares to advance legislation or defeat it, and how to build coalitions and networks.’

Counseling the counsel

The experienced general counsel we spoke to have put in the years to develop the comprehensive scope and alliance-building skills necessary to succeed at leading the legal organization in top corporations. So what advice can older hands give to those navigating less familiar waters for the first time?

The right counsel for the job

‘The most important question is: does your skillset align with the needs of the corporation? I was a litigator, and we had a lot of serious litigation, so that led to my appointment. If your corporation is in a growth mode, then they’re probably looking for somebody who’s more versed in the core area of M&A deals and cross-border transactions,’ observes Sager.

‘General counsel will always have to put out the fires – that’s a given – and you need to be skilled in that. But increasingly, the general counsel is viewed as a part of a senior leadership team, and with that comes responsibilities – some way beyond knowing how to defend a litigation or handle an investigation or a crisis.’

Whatever skillset or background today’s GCs bring to the table, they will quickly discover that the role has evolved beyond individual expertise into a broad-based, proactive and strategic position. And although there is no fixed blueprint for becoming GC, let alone succeeding in the position, experienced past and present holders of the title agreed that there are a set of qualities that aspiring legal leaders should possess.

Communication skills

General counsel must bridge the gap between the legal and business mindsets, and also overcome any outmoded preconceptions that business colleagues might harbor about the dreaded ‘department of no’.

‘Lawyers tend to talk too much and write too much, and for business you need to be very succinct. Nobody has the same attention span that they used to – they’re used to these little sound bites on their mobile phones, and you can’t hand a business person a 25-page brief,’ explains Mark Ohringer, general counsel at Jones Lang LaSalle since 2003.

Horizon spotting

‘We used to sponsor a NASCAR driver by the name of Jeff Gordon, and my CEO Chad Holliday showed us this picture of Gordon in his car, circling and making a turn in one of these races,’ says Sager.

‘“You have to help us anticipate the curves”, Holliday used to say. They might create an opportunity or risk for the corporation, and you can’t be effective if you’re not thinking along those lines.’

Most of the general counsel we spoke to agreed that GCs need to be particularly attuned to all kinds of change, including societal and political developments that are ostensibly unrelated to business.

‘There are new kinds of risks that never existed before,’ says Ohringer. ‘Cyber risk, social media – none of that existed when I started practicing 25 years ago, and now they’re enormous.’

A keen eye trained on the distant horizon will assist not only in managing and mitigating risk, but in planning for worst-case scenarios. GCs can be useful in bringing together the various siloes within an organization to design future crisis response, and ensure coordination between internal and external specialist resources.

‘A terrorism situation, a natural disaster, all these things keep happening. Are we ready as a company? Because if we’re not, there can be really bad legal risks, and that’s why the lawyers have a ticket to think about it. Those kinds of things didn’t used to happen so much and now they’re pretty much commonplace, so you need to make your response ordinary course of business. Nobody should be surprised when these things happen anymore,’ Ohringer explains.

Strength of character

When times get tough, fault lines often appear around the general counsel if they are not properly negotiating what Ben Heineman has called the ‘partner-guardian tension’.

Much has been written in recent years of the importance of effective partnership between organizations and their lawyers. The office of the general counsel has matured from the in-house approximation of the partner-associate-business ‘client’ model, to a deeper and more strategic enmeshment in the fabric of the business. So far, so value-add. But GCs must have the independence of mind to walk a line.

‘You have to have that partnering relationship with the CEO and the business leaders, but at the end of the day, your real job is being guardian of the company, which requires a certain amount of independence,’ explains Heineman. ‘There’s a certain tension between these two roles: if you are just a nay-sayer – just a guardian, protecting and risk averse – you’ll be excluded from meetings, you won’t be part of the team, and you won’t be able to play a business as well as legal role. But if you’re an inveterate yay-sayer and just do what they tell you to do, you’re going to get indicted.’

These are blunt words from a veteran GC, but necessary ones.

‘I think, sometimes, this idea that the lawyer should be part of the strategy may have actually gone a little too far,’ echoes Ohringer. ‘Big companies have had some terrible things go wrong; and how come the legal function didn’t help? It may have been too protective of the company.’

‘As all this evolves, lawyers have to not get sucked into the business too much. They need to understand it in order to do their jobs, but there’s still a need to maintain some independence. I always said I should not be the last one at the bar at night after business meetings – these are not my friends and I have to keep a little separate, because if they do something wrong, I represent the company, not them.’

We look next to today’s crop of newer recruits, and examine how they are rising to the challenges faced by the modern general counsel – and what advice they give to those currently eying the job.

Amy Sandgrund-Fisher, General Counsel, Clinton Foundation

I’ve been in-house at many different organizations, from a huge pharmaceutical company, to big public-facing non-profits, to a tech start-up. I’ve been lucky to work for a variety of excellent leaders and general counsel, and I believe that has given me a leg up in this role. That diversity of experience helped me learn the flexibility required for this role and how to handle the different types of issues I regularly tackle here.

I didn’t always want to work in-house – when I came out of law school I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do – but when I got married and started thinking about starting a family, I felt if I wanted to continue to be a lawyer and practice actively, in-house was the best route to go. I had watched women leave large firms to go in-house for years. I think in-house roles have always been perceived as better for women, because there are more development and promotional opportunities and a better work-life balance. In reality, my experience has been that being in-house is a better place for both women and men – and especially for working parents. Those development and promotion opportunities do tend to happen in a much more fluid way in-house.

Now, as general counsel, I see my role more than anything as a problem-solver. The biggest leap into this role required relying on my judgement and having the confidence to back myself. I had been an employment lawyer for almost 20 years before I became a general counsel, and it was tricky to take the confidence I had in my judgement as an employment lawyer, and transfer it to other legal areas. It only took a couple of days, though, to see that, even with my focus on employment law and my varied career, I’ve had exposure to all kinds of different legal and business matters.

To get that exposure, it was key to work at different organizations with different risk appetites, different business models and different types of leadership. Exposure to a diversity of legal problems and problem-solvers prepares you for a job like this. Given my own experience, my advice to attorneys looking to move into a GC role is to take chances and to not hesitate to try different organizations and different types of roles, and don’t get stuck. Being at one place for too long can make it hard to have the flexibility and exposure you need to take on a role like general counsel.

As for other challenges in coming to this role, one that stands out above the rest is giving legal advice to the former President of the United States for the first time! In terms of the wow factor, you can’t beat that.

Beyond that, moving from a fast-paced technology startup to the Foundation has been a challenging transition. Adjusting my pace of work and the way I think about risk assessment to a much more careful and deliberate approach took some adjustment. Even though every place has to manage reputational risk, managing it at the Clinton Foundation is different from most others.

Probably what prepared me best for that aspect of this role was working at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Museum is also a public-facing institution that gets an enormous amount of press, so the risk appetite there is pretty similar to that of the Foundation. The way in which the legal department at the Met thought about issues and how they might play out at the Museum was quite similar to the way that we think about issues here: first, of course, is what is the right thing to do? Then we start thinking about if we get media coverage, what would it look like, what would it mean for the roles of the principals, how would this reflect on board members? Those are questions that a tech startup or a big pharma company wouldn’t necessarily be thinking about in the same way.

About 80% of the work I do at the Foundation is typical general counsel work, ranging from board governance matters to reviewing partnership agreements and large contracts, weighing in on compliance issues, advising on legal matters in foreign countries, working with outside auditors, HR-type issues, as well as being a member of the senior leadership team. The other 20% is special because we are the Clinton Foundation: I might be working with our communications team responding to media requests, or managing issues that are specific to our particular board leadership, the Presidential Center and work around the President’s legacy.

I’m proud to be working for the Foundation and to get to see the work it does up close and through the legal lens. Whether it’s helping small shareholder farmers in Africa, fishermen and women in South America, or folks struggling here in the US, all the programs that the Foundation runs are incredibly important, and getting to be a part of them is rewarding. Right after I started here, the massive hurricanes hit in Texas, Florida and the Caribbean. The legal department supports the Foundation’s work in the Caribbean which includes helping to coordinate aid, working with Caribbean countries in their efforts toward alternative power solutions and distributing medical supplies to devastated areas. Even being a small part of that has been very, very gratifying.

The legal department at the Foundation is a very strong and diverse group, and many of the members of the department have been at the Foundation for quite a while. One of my goals is to make sure those individuals see a path forward for their careers. I’ve benefited from working for several strong leaders who took a keen interest in my development as a professional. I’m looking for ways to do the same for my colleagues at the Foundation. When you’re in a small team at a relatively flat organization, it can be hard to help individuals figure out how to develop themselves and what the right next career steps are. I think that being an excellent people manager is becoming a very important role for general counsel – really understanding who’s on your team, where they’re looking to go, and how you can help them get there. We all want to have high-performing teams that make important contributions to the organization. Getting there is not something they teach you in law school.

Luckily for me, I have a partner in the Foundation’s HR department. We have a strong mentoring program here and other learning opportunities to help employees at the Foundation develop career-wise. As general counsel, I view it as my job to make this in-house legal team a great place to work. That means making sure the work is interesting and challenging, that the team is diverse and that individuals can see a path forward for their careers, and that they can balance their work life with all the other things that they need and want to spend their time on.

The other thing I’ve been thinking about is the use of metrics. We haven’t used them a lot in the legal department at the Foundation (although of course the Foundation uses them to measure the work we do around the world), but it’s something I’m looking at more closely to make sure that the legal department is spending the most time on the work that’s most important to the Foundation. One thing I learned working in the start-up world is that understanding the work qualitatively, and quantitatively, even in the legal department, is part of the good management of the group.

No matter what your practice, getting international experience is incredibly important. I think it is great advice for all in-house attorneys these days to get international exposure. Whether it’s doing an international deal, working on setting up entities internationally, or working on an employment law issue or lawsuit internationally – anything that gets you out of your US jurisdiction to see how different it can be to practice in other places is a good start. Just knowing what questions to ask if you are going to be doing business in Japan, or Malawi or Colombia will put you a step ahead of colleagues without those experiences.

Brian Israel, General Counsel, Planetary Resources

For the eight years prior to joining Planetary Resources, I was in-house counsel with the US State Department, in the Office of the Legal Adviser. I spent the first couple of years handling international arbitration matters on behalf of US investors involved in disputes with foreign governments. I then spent six and a half years working on international technology matters – partnerships for the development of technology, for regulation of advanced technologies including outer space, and I also was responsible for international environmental matters, including in the Arctic.

I came to the State Department with a bit of an unusual background for an international lawyer, having focused on IP and technology law as much as international law. Because of my IP background and my comfort and facility with technical subject matter, a lot of the State Department’s work involving science, advanced technology, and innovation policy accreted to me over the years, and I was able to handle a lot of international technology transactions over the course of my time there.

Planetary Resources recruited me as its first general counsel a little more than a year ago. I think that they’d seen me in action in the years in which I was the US representative to the United Nations Outer Space Legal Subcommittee, and in space policy circles, crafting legislation for the next generation of commercial space activities. I had wanted to go in-house at a technology company, and this was a particularly compelling opportunity because the team is just extraordinary – it’s an exquisite collection of professionals and colleagues working on a very difficult world-changing mission.

I think I was as interested in space as any young person with a pulse, but compared to many I work with, it wasn’t a primary passion. I am more generally interested in technology, technological innovation and the research and development process – and space resource utilization, as a next frontier within the next frontier, is particularly interesting in this regard. And in that sense, working with a team of talented engineers and scientists on really hard problems – particularly ones that present difficult questions with regard to regulatory and economic dimensions, in addition to the technical dimensions – is quite satisfying.

Very few days have gone by in the last year when I haven’t done something entirely new to me – if not entirely new, period! But the leap was not as much as I expected, and actually eight years as an in-house counsel at the State Department turned out to be pretty good training. At the State Department, I found myself fielding questions that no one had ever thought about on quite a regular basis and I had to do something with them, so I found the pace of the GC role familiar. I think it uses a lot of the same muscle groups that I had developed in guiding large, international partnerships and transactions through to completion. In the past those might have involved governments, and the form might have been a treaty, but it was a similar skillset, a similar set of dynamics and similar challenges that arose, which felt very transportable to complex corporate transactions.

I feel strongly that the role of the general counsel, particularly in a technology company, requires enough of an understanding of the company’s technology to understand how to optimize legal transactions to facilitate research and development, rather than constrain it. I feel like I’ve had good success in doing that and working very closely with our technical teams to understand their needs, their interests and what the pain points are, and also to help them to understand the legal landscape and to craft creative legal solutions that dispense with things that might have placed drag on the innovation process.

I think that it’s quite important for the GC to be able to understand the technology and the business well enough to be able to provide legal advice not in isolation, but that integrates an understanding of the business and technical dimensions as well. The general counsel doesn’t need to be able to design the spacecraft (and probably shouldn’t!) but they do need to understand the key points of what challenges the engineers are facing, and where there are legal solutions that can mitigate some of those challenges.

On the practice management side, necessity is the mother of invention. Being a GC of a company at this stage, there is so much to do in any one day, across so many different things, that you need to be quite creative in managing work flow. I’ve taken advantage of the very talented software developers at Planetary Resources to create systems and workflows to manage how we handle non-disclosure agreements, for example. Part of it is process design, part of it is a little bit of back-end automation, but things like that make a difference not only in preventing me from becoming a choke point, but I think also have served the users of those documents well.

For some things, like funding rounds, you need the horsepower of a large firm to move with the speed and quality that we need. But also, in a startup that has big world-changing mission and vision relative to the size of its budget for outside counsel, I’ve had to be quite creative and sparing with what I do in-house versus what is outsourced. I’ve done some experimentation to figure out what’s possible, and whether we can do more with less. One example is that I’ve experimented with preparing some patent applications in-house, and worked with patent counsel to refine, finalize and file them – which is a large work burden in-house, but enables us to file for more patents than we would otherwise.

There seems to be smaller practitioners, even solo practitioners, with sterling credentials who have experience both with the very top firms and also in-house, who are providing services at comparatively approachable rates. There are all kinds of software platforms springing up too, that connect in-house legal departments with those people, who are harder to find. I can’t say whether that’s a trend yet, but it’s certainly interesting, because as a GC in a startup who is doing lots of different things on lots of different fronts, you have to be quite creative on how to stretch the budget for outside counsel. Anything that allows us to get the same level of quality for less is quite attractive, and something we will probably explore.

A fun part of the job is the chance to be a pioneer in determining how the international legal framework applies to space resource utilization and how the national legal frameworks plug into that, and that fits very well with my background. Right now, for example, I’m in The Hague at something called Track 1.5 diplomacy, where representatives of governments, academic institutions, companies and NGOs come together outside of a formal treaty-making process to try and develop a set of building blocks that might later be injected into a law-making process. But that’s a rather small percentage of what I do day-to-day. I do more in the realm of either corporate transactions, IP, contracts, export controls, as well as labor and employment law. There’s quite a lot of Delaware corporate law, for example, which makes it challenging to stay on top of, but ultimately makes for more certainty in the answers.

The general counsel of a company as innovative as Planetary Resources needs to see himself or herself as an integral part of that innovation engine. It’s too easy as a lawyer to be quite conservative and risk averse in ways that can choke the innovation process, so it’s incumbent on the GC to have a very good understanding of where the risks and opportunities are, and to have excellent judgement in balancing that to enable the rate of innovation that our investors expect, without taking on undue amounts of risk.

David Yawman, General Counsel, PepsiCo, Inc

I started out at a big Wall Street firm. I received excellent training, and worked on different matters for different clients, but I aspired more than anything to work for one single client.

I was just a fourth-year associate when I transferred into PepsiCo, which was nearly 20 years ago – so I’ve essentially had a career within a company. When I joined, the law department had a reputation for insourcing as much of the work as possible, and that was critical to me because I needed to continue to learn.

That’s really been my story for nearly 20 years – PepsiCo is a place where if you do your current job really well, we will let you do something different, even if you don’t theoretically have the experience from a subject matter perspective. I’ve had the opportunity to do a lot of different things internally that I don’t think I ever would have gotten if I had gone to the open market. So it’s been a good learning environment for me, and it’s in the DNA and the culture of PepsiCo to allow that to happen.

I’ve had the benefit of being at the company for a long time, so I think I have a good understanding of the business, the organization, the risk profile and the risk tolerance. But in taking the role of general counsel, the biggest learning curve for me was the necessity to really lift my perspective from any one particular part of the company, to an overall perspective – a broader view. The decisions that I’m involved in now definitely impact different parts of the company, and making sure that I understand and appreciate the multifactorial element of any one decision across the global business is really important.

Currently, I oversee the company’s worldwide compliance and ethics, public policy and government affairs, and legal functions. I often find myself cross-checking what impact there may be in any one of those departments, even when the issue doesn’t squarely fit within that particular department, in order to ensure that I’m not missing a potential impact of a decision made in one part of the company on another part of the company.

It’s hard for me to concede that anybody would be prepared, on day one, to handle all the various aspects of my role. No matter what background anybody would have, there’s going to be learning that would have to happen after you get into the role. I’m biased, but the benefit of having worked at PepsiCo for so long has meant not having to learn so much about the business, which can be very difficult to get to by itself. My time is very much pulled into matters that are global in nature, rather than the detailed parts of the business, but fortunately I have been able to learn the business from the ground up.

I would love to be able to tell you about some Thomas Edison-like moments during my first 100 days in the job in which I have innovated and invented something that’s new and novel! I can’t say that I’ve done that. But what I would say, having practiced law for 25 years, is that there’s been ongoing, continuous improvement. You’re constantly finding ways to do things a little faster, a little quicker, a little bit more insightfully. Certainly the sharing of information and the storing of knowledge is an important part of what we do, and the things that we’ve invested in within the legal team are really around information preservation, as well as enabling more efficient flow of work.