Alex Novarese, The In-House Lawyer: How do people feel about the service from law firms?

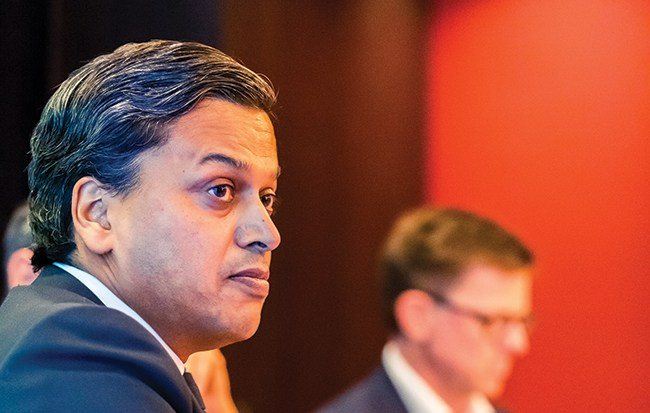

Simon White, Cognizant: There are a lot of individuals I like a great deal but as institutions, I struggle with law firms as a concept.

Alex Novarese: Because?

Simon White: I work at a company that has a large legal team. Over 300 globally. The things that are specialisms for us, we have some of the best lawyers in the world. Areas where we go out to counsel I struggle to get consistency. I do not regard myself as having a relationship with law firms; I have relationships with individual partners.

Lucy Vernall, Funding Circle: I agree entirely. Very often you can have a very good relationship with an individual partner or associate who can give you very good advice, but they involve the rest of the team and there is no consideration around whether that relationship will work.

Charles Sermon, Mereo BioPharma: Consistency across continents in your main markets is key for us.

Michael Siebold, Interlaw: Is there any guidance you could give us to reach that consistency?

Zoë Aldam, Financial Times: Even if there is consistency of quality there is not necessarily consistency of approach. You can get contrasting approaches from lawyers working on the same matter but in different jurisdictions. That’s challenging.

Alex Novarese: What are the structural impediments in the legal industry to improving global service?

Simon Evans, Vesuvius: There are different jurisdictions and different cultures. Some firms address these challenges by moving their people around between offices to ensure consistency. That is one of the solutions.

Lucy Vernall: There is a problem with a lot of lawyers giving a view. It might be OK when you need some black and white advice but when you need something more complex, even in the UK, it is quite hard to get. In the US, it is sometimes hard to get. Certainly, in other jurisdictions it is really hard to get.

Alex Novarese: Are there any jurisdictions where you get better service on a cultural level?

Charles Sermon: We find that because we do a lot of work with US lawyers and UK lawyers and some of the firms that we have worked with do send people from the UK to the Washington office or the San Francisco office, they get experience working together. That is amazingly helpful.

Alex Novarese: It is a cliché to say technical excellence is a given. Is that true?

Simon White: I would never go to a law firm on GDPR.

Alex Novarese: Because?

Simon White: We are all in the same boat – all learning what GDPR is. Most lawyers and law firms do not understand how companies work in terms of process and people. The biggest thing about GDPR is culture change within an organisation. That is not something lawyers sitting in a nice office in the City really understand.

Daniel Lichtenstein, Grant Thornton International: Law firms have industry specialisms. That tends to be attractive to companies in a specific industry. Just because a firm is a global firm I do not think I could assume technical expertise.

Alex Novarese: Hourly billing has been a bugbear for years. GCs are great. We love them. But it is kind of your fault, is it not?

Simon White: It is.

Alex Novarese: What I would take from that is it is in the interest of many GCs to have hourly billing because if it wasn’t, it would have gone already.

Simon White: I am not sure that is right. Law firms are the last professional service industry that is obsessed with T&M. Everyone else is driving to different models. OK, you can throw it back on us as customers and say, ‘Why are you not doing that?’ but other professional service firms we use in consultancy do not do that.

Alex Novarese: Bluechip consultants are value for money?! That is a new one.

Simon Evans: From an in-house lawyer’s view, the best way of controlling fees is to tender for everything because you would reduce the price. You can do that for certain work but not others. It may be too sensitive, too confidential, too urgent. Then, ultimately, the law firms have their own profit models, which are based on time. There is a lot of competition coming in. However, for the bigger ticket work, they still get away with it.

Alex Novarese: There are a lot of transactions that get funnelled to a very small group of law firms, even though it is not six firms that can do it; it is 26 or 56. Ultimately, what does the IBM factor mean? It means somebody did not want to put their name behind hiring somebody other than IBM. And that somebody is sitting around this table.

Simon Evans: You are right. The GC would have to convince the board that a slightly less familiar name is going to do the job well. If they are prepared to pay more, it is less risk on you.

Michael Siebold: I have never understood why lawyers would sell on an hourly basis. Legal advice does not necessarily have to be the cheapest. It has to be worth the price that you are paying. We can price everything. If we cannot, we should not be your firm.

Alex Novarese: How easy is it for people around the table to benchmark market rates for various kinds of job?

Simon Evans: You have a sense of what something should reasonably cost and know that will vary a bit by jurisdiction and law firm, but you think that is probably lower than the law firm’s figure. If you go into a new legal area, then your certainty will be lower but you have probably seen most types of transactions to give you an idea of an appropriate cost.

Alex Novarese: Yet the legal market is stunningly opaque.

Simon White: I do not feel I have any way of benchmarking against what other corporates are paying for similar things. I know what I think is a fair price but if I get three or five firms to pitch for that work, I do not know how that compares to what they then pitched the week before to someone else. It is odd because in the tech industry, benchmarking rates are critical.

Alex Novarese: Is the next stage where you start to build your own Lawyers On Demand?

Patrick Crumplin: That suggests fundamental change in the whole business model, not just how you price a particular project.

Alex Novarese: How do law firms compare in service levels and the issues we have been talking about to banking, consultancy or accountancy?

Lucy Vernall: Banks are not very good at it. They work on a relationship basis. They have their fingers in everything and are instructed because of who is on the board. Accountants, while they charge you on a different basis, are on the sell constantly. Often if you are on a project where you have banks, accountants and lawyers, the lawyers are providing by far the best service.

James Wood, The In-House Lawyer: Has anyone worked with the legal services arms of the Big Four?

Lucy Vernall: Yes. I have not done it for a long time, but I would not work with them again. I did not think their quality was particularly good. The time they come up is when you are dealing with one of the Big Four and they are doing a project for you and they say, ‘We are not advising on the legal bit’ because there is a very narrow scope of work that involves not very much and everything else is outside it. The work that lawyers are doing is fairly simple and I do not think they have done it particularly well.

Charles Sermon: Also, you have to be very careful because if you have an audit risk committee there are certain guidelines on non-audit services. Even if you wanted to use the legal arm of your auditor for services, you are limited as to how much you can do. We do not [use them].

Simon White: They are often not selling legal services. With GDPR, for example, the Big Four have all gone and hired whoever can spell the word privacy. On the legal bit there is not the structure that checks the quality and consistency. You are with a very, very random group of lawyers who do not know whether they are giving legal advice or not.

Alex Novarese: Are clients aware if your advisers operate through a network, or do you just focus on the end result?

Simon Evans: If it is a genuinely multijurisdictional legal practice and the model works, the seamless international service delivered wherever you want it is fine. The danger is if it has weak links and you are trapped into a network that has four good offices and three poor ones.

Lucy Vernall: It potentially is easier if it is properly managed to get good consistency and quality through a network than through a big international law firm, particularly one made up through mergers.

Alex Novarese: Michael, how do you do it?

Michael Siebold: We are non-exclusive in the sense we do not have to use our member firms. We use the best firms locally that we have. Now, we also know what the member firms cannot do. In situations where they are not able to handle something we would ask them to provide somebody more capable. We also do a tri-annual review where we run due diligence, in most cases with a personal visit. On every matter, the sending firm, the receiving firm and, hopefully, the client will tell us whether we did well or not. It is a scale of one to five; three is not good. Two is acceptable, one would be best. On three, we ask what went wrong? Less than that, we talk about whether we have the right member.

Alex Novarese: Law firms never shut up about their culture. Do clients notice it in the service?

Michael Siebold: Again, assuming I understand what you want, I then pick the right people. I can vouch for the quality because my relationship with you would be on the line.

Simon White: Then there is a question about whether you pay for that client management piece of that project management piece.

Alex Novarese: Giving law firms a rest, what do our in-house legal teams do now that they should stop doing?

Daniel Lichtenstein: Not using technology enough. It should be built into how the department works, from billing management to control management. It is also related to GCs needing to upscale their own technical expertise.

Alex Novarese: So much resource is going on lawyers directly, the lawyers you employ or pay externally, rather than other skills, whether technology or other business services.

Daniel Lichtenstein: Yes, but also being able to assess the value-add through technology. There is a great opportunity to integrate technology into everything the GC does.

Simon White: I would also say to my team that we spend too much time looking at the contracts and are missing the wood for the trees. I have just come from a board meeting earlier this week and the board were asking about contracts. We have unlimited liability and they are obsessed with this. That is irrelevant.

Charles Sermon: Automation improving processes and efficiencies might scare some people. I encourage the junior people at the coalface to come up with ideas about how we could be more efficient. I engage them there so it is not threatening to them.

Simon White: AI is a thing we are still in transition in understanding. Five years ago, people thought of automation as robots and humans disappear. People now talk about the smart hand or the smart robot hand. The humanity becomes far more important. I work in a massive tech company but in the last five years is we are employing fewer engineers and mathematicians. We are employing people now who do history, theology and psychology because understanding the human piece on whatever we do is super important. Your juniors may be fearing AI, but it is about thinking about what the new skills they need are. Maybe they do not have to become a lawyer but can introduce new skills.

Alex Novarese: How do people see in-house evolving in the next five to ten years?

Simon Evans: We are going to have to use technology more, which is challenging in getting it right because there is an upfront cost. There is also a separate demographic issue with more law graduates being churned out.

Nayeem Syed, Thomson Reuters: The in-house function will still be important. But it will likely change. There is more regulation, more compliance and more complexity. Business models are being challenged at an unprecedented rate so there is more pressure to do more innovative things more quickly. Our work will focus less on pro-forma contracts or standardised advice. Internal clients and external partners are looking for legal teams to step up and give commercially focused legal views that people at different levels and with different training will understand. Those that can operate comfortably when faced with uncertainty and are willing to apply legal frameworks to new situations to achieve organisational goals will be valued and supported. If you cannot show that, it is more likely that you will be excluded from key discussions and perhaps eventually the organisation itself.

Lucy Vernall: You have to be able to show the data. It is not just about cutting external legal fees. How do you use technology? People want a business partner. You need to be making yourself more efficient.

Simon White: We are in much more of a mixed model moving forward. There is not a single solution to anything. In-house teams are going to contract. Law firms will contract but there are going to be all sorts of other things out there. It is challenging the boundaries of what is and is not legal advice and we are starting to get less hung up on those pieces and understanding whether this is business advice. There is no solution yet but that is where we are heading.

Alex Novarese: Thank you for your time.

The panellists

- Zoë Aldam Financial Times

- Ned Beale Trowers & Hamlins

- Patrick Crumplin Duff & Phelps

- Simon Evans Vesuvius

- Daniel Lichtenstein Grant Thornton International

- Michael Pattinson Trowers & Hamlins

- Charles Sermon Mereo BioPharma

- Nayeem Syed Thomson Reuters

- Lucy Vernall Funding Circle

- Simon White Cognizant

- Imogen Lee Interlaw

- Michael Siebold Interlaw

- Alex Novarese The In-House Lawyer

- James Wood The In-House Lawyer