Of all current technological innovations, artificial intelligence has undoubtedly generated the most hype, and the most fear. Wherever AI goes, the image of a dystopian future is never far away, nor is a conference room full of nervous lawyers.

The reality, of course, is quite different. Some corporate legal teams, particularly those already in the tech field, or those at companies handling huge amounts of customer data are ahead of the curve. But, for many in the legal world, the future is a far-off land – for now.

‘When you hear people saying that tomorrow everyone will be replaced by robots, and we will be able to have a full, sophisticated conversation with an artificial agent… that’s not serious,’ explains Christophe Roquilly, Dean for Faculty and Research, EDHEC Business School.

‘What is serious is the ability to replace standard analysis and decisions with robots. Analysis further than that, when there is more room for subjectivity and when the exchange between different persons is key in the situation… we are not there yet.’

Much of the conversation around AI, particularly in the in-house world, remains a conversation about potential. The expanding legal tech sector is teeming with AI-based applications in development, but on the ground, even in the legal departments of many of Europe’s biggest blue chips, concrete application appears to be limited.

‘I think the US may be a bit further down the road than Europe. AI is coming, people are thinking about it, some in a partial way, but it will be developing quickly in the coming years. It may have more or less the same role as the internet had 15 years ago changing radically the way we work, but we’re not there yet,’ says Vincent Martinaud, counsel and legal manager at IBM France.

‘While the legal function may change to the extent that there are tasks we may not do anymore in the future, does that mean we will be disrupted? I don’t think so.’

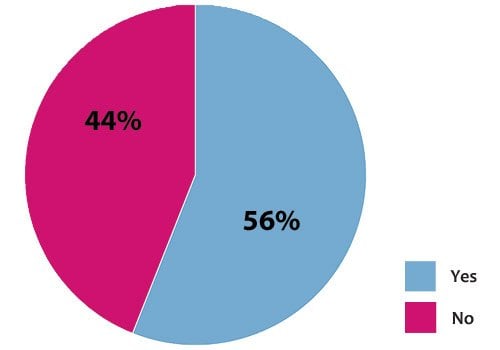

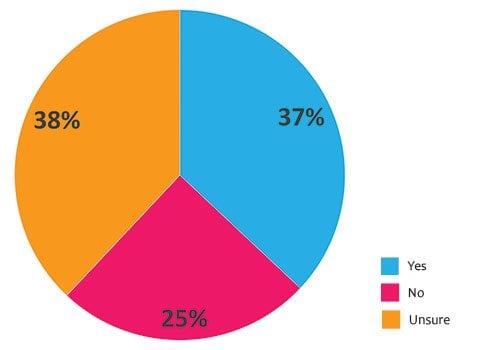

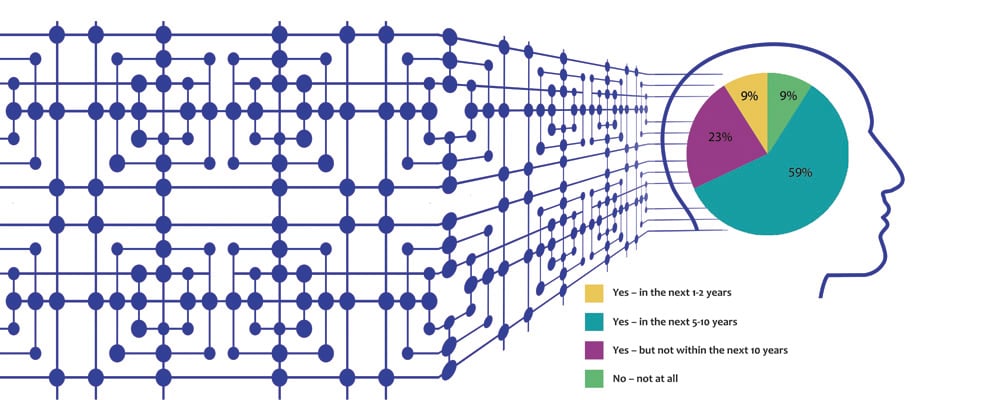

Those views largely align with the general counsel surveyed across Europe on AI.

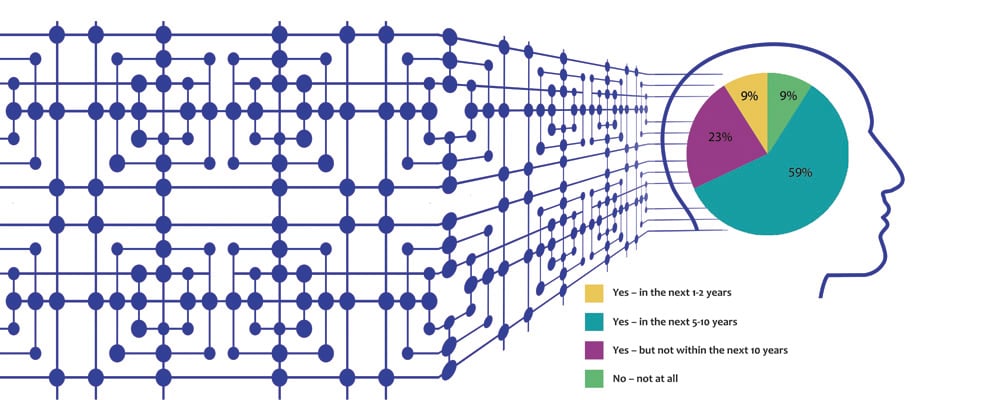

Only 9% of those surveyed anticipate AI becoming a disruptor in the legal industry within the next two years. 59% of those surveyed expected AI to be a disruptor within the next five to ten years, with the remaining 32% saying it would not be a disruptor within the next decade.

Understanding Argument – Professor Katie Atkinson, head of the department of computer science at Liverpool University

‘You can model argumentation in all sorts of different specific domains, but it’s particularly well suited to law because arguments are presented as part of legal reasoning.

It could be a computer arguing with a human, or it could be two machines arguing autonomously. But it’s basically looking at how arguments are used in order to justify a particular decision and not another alternative. We do that through constructing “formal models”, so you can write algorithms that can then decide which sets of arguments it is acceptable to believe together. That provides you with automated reasoning and, ultimately, a decision about what to do and why.

While the legal industry may represent a potentially lucrative market for software developers, it does not offer the potential gains of sectors like healthcare or finance.

‘In AI, we see many developments with our cars, many developments in the healthcare sector, and therefore changes in these sectors will probably come faster. In the legal field we do see changes, but I don’t think we are at the edge of it,’ notes Martinaud.

With relatively few lawyers utilising AI solutions at present (8.8% of survey respondents reported using AI solutions – with all applications being in low-level work), perhaps it’s time for a reality check.

Applications

For many in-house counsel, the chat bot is the most readily available example of how AI (in a first-stage form) can make life easier for in-house teams. At IBM, Martinaud is using Watson, the company’s deep learning AI for business. Through this platform, the legal team uses, for instance, a chat bot called Sherlock, which can field questions regarding IBM itself – its structure, address, share capital, for example. The team is also working on a bot to answer the myriad queries generated by the business on the topic of GDPR, and on a full data privacy adviser tool which can receive and answer questions in natural language.

‘These are the kinds of questions you receive when you’re in the legal department, and it’s very useful to have these tools to answer them or to ask the business to use the tool instead of asking you,’ says Martinaud.

‘An additional example of Watson-based technology that the legal team has started using is Watson Workspace, a team collaboration tool that annotates, groups the team’s conversations, and proposes a summary of key actions and questions, which is organised and prioritised.’

Another early use-case for AI in the legal profession has been the range of tools aiming to improve transparency in billing arrangements.

Last year, IBM stepped into the mix with Outside Counsel Insights, an AI-based invoice review tool aimed at analysing and controlling outside counsel spend. A product like Ping – an automated timekeeping application for lawyers – uses machine learning to track lawyers as they work, then analyses that data, turning it into a record of billable hours. While aimed at law firms, its applications have already proved more far-reaching.

Daniel Saunders, chief executive of L Marks, an investment and advisory firm that specialises in applied corporate innovation, says the technology is a useful means of monitoring service providers’ performance.

‘As someone who frequently is supported by contract lawyers et al., increasing the transparency between the firms and the clients is essential. Clients have no issue paying for legal work performed, but now we want to accurately see how this work translates to billable hours,’ he says.

‘Furthermore, once law firms implement technologies like Ping, the data that is gathered is going to be hugely beneficial in shaping how lawyers will be working in the future.’

Information management

The clear frontrunner in terms of AI-generated excitement among the corporate legal departments who participated in the research for this report was information management, which can be particularly assisted by developments such as smart contracting tools.

‘Legal documents contain tremendous knowledge about the company, its business and risk profiles. This is valuable big data that is not yet fully explored and utilised. It will be interesting to see what AI can do to create value from this pool of big data,’ says Martina Seidl, general counsel, Central Europe at Fujitsu.

Europe’s race for global AI authority

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is on course to transform the world as we know it today. A 2017 study by PwC calculated that global GDP will be 14% higher in 2030 as a result of AI adoption, contributing an additional €13.8tn to the global economy. The same study states that the largest economic gains from AI will be in China (with a 26% boost to GDP in 2030) and North America (with a 14.5% boost) and will account for almost 70% of the global economic impact. In addition, International Data Company (IDC), a global market intelligence firm, predicts that worldwide spending on AI will reach €16.8bn this year – an increase of 54.2% over the prior 12-month period.

The runners in the AI race are, unsurprisingly, China and the United States, but Europe has pledged not to be left behind. The European Commission has agreed to increase the EU’s investment in AI by 70% to €1.5m by 2020.

Closing the gap

The European Commission has created several other publicly and privately funded initiatives to tighten the field:

Horizon 2020 project. A research and innovation programme with approximately €80bn in public funding available over a seven-year period (2014 to 2020).

Digital Europe Investment Programme will provide approximately €9.2bn over the duration of the EU’s next Multinational Financial Framework (2021 – 2025). These funds will prioritise investment in several areas, including AI, cybersecurity and high-performance computing.

European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI). An initiative created by the European Investment Bank Group and the European Commission to help close the current investment gap in the EU. The initiative will provide at least €315bn to fund projects which focus on key areas of importance for the European economy, including research, development and innovation.

However, AI funding is not the only pursuit. While China has pledged billions to AI, it is the US that has generated and nurtured the research that makes today’s AI possible. In the research race, Europeans are striving to outpace the competition with the creation of pan-European organisations such as the Confederation of Laboratories for Artificial Intelligence in Europe (CLAIRE) and the European Lab for Learning and Intelligent Systems (ELLIS). CLAIRE is a grassroots initiative of top European researchers and stakeholders who seek to strengthen European excellence in AI research and innovation, and ELLIS is the machine learning portion of the initiative.

One main hurdle stands in the way of Europe and its run to the finish: the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). GDPR regulates EU organisations that use or process personal data pertaining to anyone living in the EU, regardless of where the data processing takes place, at a time when global businesses are competing to develop and use AI technology. While GDPR forces organisations to take better care of personal client data, there will be repercussions for emerging technology development. It will, for example, make the use of AI more difficult and could possibly slow down the rapid pace of ongoing development.

Individual rights and winning the race

Europe has plotted its own course for the regulation and practical application of legal principles in the creation of AI. Ultimately, the advantages of basing decisions on mathematical calculations include the ability to make objective, informed decisions, but relying too heavily on AI can also be a threat, perpetrating discrimination and restricting civilians’ rights. Although a combination of policy makers, academics, private companies and even civilians are required to implement and maintain ethics standards, continue to question AI’s evolution and, most importantly, seek education in and awareness of AI, it will be a coordinated strategy that will make ethics in AI most successful.

For Nina Barakzai, general counsel for data protection at Unilever, AI-powered contracting has proved to be a real boon in understanding the efficacy of privacy controls along the supply chain.

‘Our combined aim is to make our operations more efficient and reduce the number of controls that are duplicated. Duplication doesn’t help those who are already fully loaded with tasks and activities. Where there is confusion, it should be easy to find the answer to fix the problem,’ she says.

‘That’s where AI contracting really comes into play, because you analyse how you’re doing, where your activity is robust and where it isn’t. It’s a kind of issue spotting – not because it’s a problem but because it could be done differently.’

At real estate asset management company PGIM Real Estate, the focus of AI-related efforts has been to build greater efficiency into the review of leases, to enable a more streamlined approach to due diligence. The legal team approached a Berlin-based start-up that had developed a machine-learning platform for lease review.

‘Since we do not want the machine to do the entire due diligence, we use a mixed model of the software tool reviewing documentation and then, for certain key leases which are important from a business perspective, we have real lawyers looking at the documentation as well,’ says Matthias Meckert, head of legal at PGIM.

‘It’s a lot of data gathering and a machine can do those things much better in many situations: much more exact, quicker of course, and they don’t get tired. The machine could do some basic cross checks and review whether there are strange provisions in the leases as well.’

Similarly, transport infrastructure developer Cintra has looked to the machine-learning sphere for the review and analysis of NDAs, and is almost ready to launch such a tool in the legal department after a period of testing is completed.

‘People always find the same dangers in that kind of contract, so it’s routine work. It can be done by a very junior lawyer – once you explain to that lawyer what the issues are, normally it’s something that can be done really quickly,’ says Cristina Álvarez Fernández, Cintra’s head of legal for Europe.

Far from being a narrative about loss of control, AI in the in-house context is as much a story of its limitations as its gains.

Do you think that AI will be a disruptor in the legal industry?

‘If your own process is not really working right, if you don’t have a clear view on what you’re doing and what are the steps in between, using a technology resource doesn’t really help you. What do I expect, what are the key items I would like to seek? You need to teach the legal tech providers what you would like to have – it’s not like somebody coming into your office with a computer and solving all your problems – that’s not how it happens!’ says Meckert.

When introducing AI solutions – or any technology for that matter – having a realistic understanding of what is and isn’t possible, as well as applying a thoughtful and strategic approach to deployment is critical to gaining buy-in and maximising potential.

‘The risk is of treating new software capability as a new shiny box: “I’ll put all my data into the box and see if it works”. My sense is that AI is great for helping to do things in the way that you want to do them,’ says Barakzai.

Emily Foges, CEO, Luminance

‘The decision to apply our technology to the legal profession came out of discussions with a leading UK law firm, and the idea of using artificial intelligence to support them in document review work was really the genesis of Luminance, which was a great learning experience. For example, we had to teach Luminance to ignore things like stamps – when you have a “confidential” stamp on a document, to begin with, it would try and read the word “confidential” as if it was part of the sentence.

We launched in September 2016, targeting M&A due diligence as an initial use-case: an area of legal work in pressing need of a technological solution. Since then, Luminance has expanded its platform to cater to a range of different use-cases. The key to Luminance is the core technology’s flexibility, making it easily adaptable to helping in-house counsel stay compliant, assisting litigators with investigations, and more.

When a company’s documents are uploaded to Luminance, it reads and understands what is in them, presenting back a highly intuitive, visual overview that can be viewed by geography, language, clause-type, jurisdiction and so on, according to the user’s preferences. The real power of the technology is its ability to read an entire document set in an instant, compare the documents to each other to identify deviations and similarities, then through interaction with the lawyer, work out what those similarities and differences mean.

I view the efficiency savings of Luminance as a side benefit. As a GC, you want to have control over all your documents – know what they say, know where they are, know how to find them, know what needs to be changed when a regulation comes along, and have confidence that you have not overlooked anything. I think the real change we are seeing with the adoption of AI technology by in-house counsel is that lawyers are able to spend much more time being lawyers and much less time on repetitive drudge work. They are freed to spend time providing value-added analysis to clients, supported by the technology’s unparalleled insights.’

‘If you’ve got your organisational structures right, you can put your learning base into the AI to give it the right start point. My realism is that you mustn’t be unfair to the AI tool. You must give it clear information for its learning and make sure you know what you’re giving it – because otherwise, you’ve handed over control.’

Tobiasz Adam Kowalczyk, head of legal and public policy at Volkswagen Poznan, adds: ‘Although we use new tools and devices, supported by AI technologies, we often do so in a way that merely replaces the old functionality without truly embracing the power of technology in a bid to become industry leaders and to improve our professional lives.’

What’s in the black box?

Professor Katie Atkinson is dean of the School of Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Computer Science at the University of Liverpool. She has worked closely with legal provider Riverview Law, which was acquired by EY in 2018, and partners with a number of law firms in developing practical applications for her work on computational models of argument. This topic falls within the field of artificial intelligence and seeks to understand how people argue in order to justify decision-making. Her argumentation models are tested by feeding in information from published legal cases to see if the models produced the same answer as the original humans.

For Atkinson, a key aspect of the work is that it does not fall prey to the ‘black box’ problem common to some AI systems.

‘There’s lots of talk at the moment in AI about the issue of an algorithm just spitting out an answer and not having a justification. But using these explicit models of argument means you get the full justification for the reasons why the computer came up with a particular decision,’ she says.

‘When we did our evaluation exercise, we could also see how and why it differed to the actual case, and then go back and study the reasons for that.’

From a practical perspective, engendering trust in any intelligent system is fundamental to achieving culture change, especially when tackling the suspicious legal mind, trained to seek out the grey areas less computable by a machine. But Atkinson also sees transparency as an ethical issue.

‘You need to be absolutely sure that the systems have been tested and the reasoning is all available for humans to inspect. The results of academic studies are open to scrutiny and are peer reviewed, which is important,’ she says.

‘But you also need to make sure that the academics get their state-of-the-art techniques out into the real world and deployed on real problems – and that’s where the commercial sector comes in, whereas academics often start with hypothetical problems. I think as long as there’s joined-up thinking between those communities then that’s the way to try and get the best of both.’

British legal AI firm Luminance also finds its roots in academia. A group of Cambridge researchers applied concepts such as computer vision – a technique typically used in gaming – in addition to machine learning, to help a computer perceive, read and understand language in the way that a human does, as well as learn from interactions with humans.

CEO Emily Foges has found that users of the platform have greater trust in its results when it creates enough visibility into its workings that they feel a sense of ownership over the work.

‘In exactly the same way as when you appoint an accountant, you expect that accountant to use Excel. You don’t believe that Excel is doing the work, but you wouldn’t expect the accountant not to use Excel. This is not technology that replaces the lawyer, it’s technology that augments and supercharges the lawyer,’ she says.

‘That means that the lawyer has more understanding and more visibility over the work they’re doing than they would do if they were doing it manually. They are still the ones making the decisions; you can’t take the lawyer out of the process. The liability absolutely stays with the lawyer – the technology doesn’t take on any liability at all – it doesn’t have to because it’s not taking away any control.’

This understanding of AI as a tool as opposed to a worker in its own right was essential to framing the measured response that many of our surveyed general counsel took to the revolutionary potential of AI.

‘Depending on the role of AI, it can be an asset or a liability. However, AI will prove useless to make calls or decisions on specific cases or issues. It can, however, facilitate the decision-making process,’ says Olivier Kodjo, general counsel at ENGIE Solar.

A balancing act

The increasing prevalence of algorithmic decisions has caught the attention of regulators. A set of EU guidelines on AI ethics is expected by the end of 2018, although there is considerable debate among lawyers about the applicability of existing regulations to AI.

For example, the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) addresses the topic of meaningful explanation in solely automated decisions based on personal data. Article 22 (1) of the GDPR contains the provision that:

‘The data subject shall have the right not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, which produces legal effects concerning him or her or similarly affects him or her’.

This mandates the presence of human intervention (not merely processing) in decisions that have a legal or significant effect on a person, such as decisions about credit or employment.

The UK has established an AI Council and a Government Office for Artificial Intelligence, and a 2018 House of Lords Select Committee report, AI in the UK: Ready, Willing and Able? recommended the preparation of guidance and an agreement on standards to be adopted by developers. In addition, the report recommends a cross-sectoral ethical code for AI for both public and private sector organisations be drawn up ‘with a degree of urgency’, which ‘could provide the basis for statutory regulation, if and when this is determined to be necessary.’

Europe’s Race for Global AI Authority

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is on course to transform the world as we know it today. A 2017 study by PwC calculated that global GDP will be 14% higher in 2030 as a result of AI adoption, contributing an additional €13.8tn to the global economy. The same study states that the largest economic gains from AI will be in China (with a 26% boost to GDP in 2030) and North America (with a 14.5% boost) and will account for almost 70% of the global economic impact. In addition, International Data Company (IDC), a global market intelligence firm, predicts that worldwide spending on AI will reach €16.8bn this year – an increase of 54.2% over the prior 12-month period.

The runners in the AI race are, unsurprisingly, China and the United States, but Europe has pledged not to be left behind. The European Commission has agreed to increase the EU’s investment in AI by 70% to €1.5m by 2020.

Closing the Gap

The European Commission has created several other publicly and privately funded initiatives to tighten the field:

- Horizon 2020 project. A research and innovation programme with approximately €80bn in public funding available over a seven-year period (2014 to 2020).

- Digital Europe Investment Programme will provide approximately €9.2bn over the duration of the EU’s next Multinational Financial Framework (2021 – 2025). These funds will prioritise investment in several areas, including AI, cybersecurity and high-performance computing.

- European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI). An initiative created by the European Investment Bank Group and the European Commission to help close the current investment gap in the EU. The initiative will provide at least €315bn to fund projects which focus on key areas of importance for the European economy, including research, development and innovation.

However, AI funding is not the only pursuit. While China has pledged billions to AI, it is the US that has generated and nurtured the research that makes today’s AI possible. In the research race, Europeans are striving to outpace the competition with the creation of pan-European organisations such as the Confederation of Laboratories for Artificial Intelligence in Europe (CLAIRE) and the European Lab for Learning and Intelligent Systems (ELLIS). CLAIRE is a grassroots initiative of top European researchers and stakeholders who seek to strengthen European excellence in AI research and innovation, and ELLIS is the machine learning portion of the initiative.

One main hurdle stands in the way of Europe and its run to the finish: the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). GDPR regulates EU organisations that use or process personal data pertaining to anyone living in the EU, regardless of where the data processing takes place, at a time when global businesses are competing to develop and use AI technology. While GDPR forces organisations to take better care of personal client data, there will be repercussions for emerging technology development. It will, for example, make the use of AI more difficult and could possibly slow down the rapid pace of ongoing development.

Individual Rights and Winning the Race

Europe has plotted its own course for the regulation and practical application of legal principles in the creation of AI. Ultimately, the advantages of basing decisions on mathematical calculations include the ability to make objective, informed decisions, but relying too heavily on AI can also be a threat, perpetrating discrimination and restricting civilians’ rights. Although a combination of policy makers, academics, private companies and even civilians are required to implement and maintain ethics standards, continue to question AI’s evolution and, most importantly, seek education in and awareness of AI, it will be a coordinated strategy that will make ethics in AI most successful.

‘From my end, it is the same old battle that we have experienced in all e-commerce and IT-related issues for decades now: the EC does not have a strategy and deliberately switches between goals,’ says Axel Anderl, parter at Austrian law firm Dorda. ‘For ages one could read in e-commerce related directives that this piece of law is to enable new technology and to close the gap with the US. However, the content of the law most times achieved the opposite – namely over-strengthening consumer rights and thus hindering further development. This leads to not only losing out to the US, but also being left behind by China.’

Anderl speaks to an uncomfortable reality nestled in among the ethics portion of the AI debate. While some remain concerned about the ethical questions posed by AI technology, this concern may not be shared by everyone. However, like most things, those who feel unrestrained by codes of ethics will be at a natural advantage in the AI arms race.

‘We are aware that if other, non-European global actors do not follow the fundamental rights or privacy regulations when developing AI, due to viewing AI from a “control” or “profit” point of view, they might get further ahead in the technology than European actors keen on upholding such rights and freedoms,’ explains a spokesperson from Norwegian law firm Simonsen Vogt Wiig AS.

‘If certain actors take shortcuts in order to get ahead, it will leave little time to create ethically intelligent AI for Europe.’

The ethics dimension also extends to the future treatment of employees. Despite headlines spelling doom for even white-collar professions, those we spoke to within in-house teams were reluctant to concede any headcount reduction due to investment in AI technology.

‘I don’t think this will replace entirely, at least so far, a person in our team other than in the future we would have a negotiation or similar, that we will cover that person with technology,’ says Álvarez Fernández, head of legal, Europe at Cintra.

‘I think this is going to help us to better allocate the resources that we have. I don’t think this will limit the human resource.’

And nor should it, says Atkinson:

‘You wouldn’t want to automate absolutely everything. One of the key aims with my work has been: let’s automate what we can, let’s try and improve consistency and efficiency,’ she says.

‘That ultimately helps the client and it frees up the people to do more of that people-facing work with their clients. People still want to speak to a human being on a variety of options and we still absolutely do need those checks from the humans on what the machines are producing.’

Whatever the future holds, the consensus for now seems to be that any true disruption remains firmly on the horizon – and although the potential is undeniably exciting, to claim that the robots are coming would be… artificial.

We started using special legal software about five years ago. We work completely paperless and our system is based on open tech – it’s integrated into Microsoft Outlook and is basically a legal case management system.

We have increased the number of lawyers, especially younger lawyers, because we don’t need PAs anymore as a result of our completely digital workload process.

We also use contract creation software. We have about 30 templates we are using, which are compiled from boilerplate, so we only have to change the individual boilerplate and not the complete contract, which gives us standardisation.

We use this software for more complex contracts as well – things like distribution and licensing agreements. The next step will be self-service contracts for simpler contracts, giving leads back to operations, like C2C agreements, which can then be done by a self-service team rather than the legal team. So, for example, if there’s a specific clause that should be used, we are only informed that this clause should be used and we don’t need to see the complete contract anymore.

We’re using software for legal spend, and a software tool for speech recognition – Dragon Naturally Speaking. And we are now working with our next step on workflow tools – we have just recently introduced SharePoint, so we are still assessing whether we are going to use SharePoint Flows, or another tool used in our company’s legal system, which is business project management software.

What we see is that there is a trend towards digitalisation and these things are done by automatic workflows. I hope that email correspondence will be replaced with things like assignments, so it’s no longer unilateral but bilateral that you agree what you should work on.

Keeping the team agile

We have just changed from a departmental structure to a new task-based team structure. In my department, I used to have a compliance department, a patent department and a legal department. I just scrapped the departmental structure and organised into teams.

The new structure gives team members more flexibility, and we are using new agile working methods such as Scrum. It gives more freedoms to the individual, and more responsibility as well. It goes away from the typical hierarchical structure to more self-organised working. It’s not enough to change the work or the way you use digital, you probably also need to change your departmental structure to agile methods because new IT is basically about agile.

In terms of team structure, we have a lean manager here in our legal department and I also want to create a digital legal officer. The legal profession is about five years behind usual business standards – we are not used to processes and other things that are common practice in other departments. In order to be on the same level, we need to advance in legal services. The typical handmade agreement would still be relevant, but the new role of the lawyer is more likely a legal process designer to some extent. The normal functions like fire fighting, corporate governance and compliance will still be in existence, but I would estimate that the typical contract work is going to reduce over the next five years, and be replaced by digital data processes including bots asking and answering questions – because there are already those tools available. This can be – at least for some legal work – disruptive change, and that’s why we concentrate on this: to be competitive in the future. We want to provide services that are still asked for by the company. But this will create and maintain jobs, and may even create future jobs, because it’s not just legal advising anymore – we are part of the process and the value chain.

A digital legal officer probably will not code or programme like an IT programmer, but they will compile software tools with intelligent applications. There are already tools available on the market that allow, on a high level, programming – this can be done by the individual, taking it from IT, which is too slow. We need incremental changes, not wholesale changes every three years or so.

We need to have lawyers who have some affinity to IT to specialise also in IT processes, so some of my lawyers need to be able to at least configure software if not even programme software. I personally can programme – I have learned it. To find lawyers who have affinity to IT is not easy, but we are looking for these skills nowadays when we are hiring lawyers.

Technology that works for us

I’ve been doing this for almost 30 years. When I started, computers had just started and all of the work was paper-based. The communication channels were yellow post, the telephone and maybe some rudimentary email function. Then, things evolved to the point that even a lawyer was the slave of the computer. And what I see coming, and I hope to be coming, is that computers will work for us and not us working for the computers anymore. I hate to see people sitting before a desktop all day and using email chat as the only source of communication. This is not effective, it is not efficient and it needs to change.

The challenge of employing technology is internationalisation. I have 27 legal departments worldwide, and to introduce such tools into smaller legal departments is a challenge. Is the internet speedy enough to train people to adapt technology to local needs, for example? There are legal challenges like attorney client privilege, e-discovery and, of course, EU data privacy.

The main future technology trend, I would think, should be smart contracts. Intelligent, smart contract creation and tools that help us for that purpose, in order to get rid of this standard work.

Another is effective communication. Even Skype for Business and other tools do not really replace personal communication. Often internet bandwidth is not good enough, the quality of the picture is not good enough, so there’s quite a lot which needs to develop in order to replace personal communication and save travel time.

That’s a learning curve in and of itself: replacing personal meetings with virtual meetings. It’s easy to say, but difficult to do. I just tried to have a conference of my main lawyers worldwide, through time zone differences of 12 hours, with five continents and 12 participants. It was almost impossible to have a discussion.

The third one is knowledge management – I think knowledge management, with AI and so on, will change. Typical features in a search function will be replaced – ten years ago, you were looking into books, now the first way to look is to search Google – but this will be more intelligent.

Asking the right questions

In terms of technological innovation, I don’t see the support from the law firms. Everything they offer is to increase their business and not to increase mine. That’s not enough anymore – they need to make my work easier, and not the other way around. This is a typical situation: I have an M&A deal and I am asked to use the law firm’s data room, and adapt to their way of thinking. They are still exchanging emails. So with everything I do, I have to adapt to their system. I am not interested anymore. It’s time consuming. As with many other service providers, they should look at how they give me added value with their offerings – seeing what I need and trying to offer a tailor-made solution for my purpose. They never even ask the question.

Unease with the anticipated digital and disaggregated future is real in many dusty corners of the legal profession, and with around 1,400 legal tech companies fighting for a share of the global legal services market, the prevailing story has been the threat these offerings pose to traditional law firm models. However, this narrative hides a subtler shift in how some law firms are approaching this impending disruption: they are working with the innovators, not against them.

Getting into bed with the enemy

In the past two years, law firms have started to create technology incubator programmes within their own walls. Much like the ecosystem of incubators and accelerators famous in Silicon Valley and tech hubs around the world, the idea is to take a business concept in the early stages of development and provide any combination of support, mentorship, facilities and even investment.

This shift might seem counterintuitive to some: why would the old hands team up with the young upstarts whose end goal, in many cases, is to capture the law firm’s own clientele of general counsel who are under continued pressure from the board to minimise their contribution to the $600bn dollar global industry that is big law?

For some firms, engagement with start-ups is the result of a process of introspection, one that began in an attempt to root out the pain points of its lawyers’ working lives.

This growing cohort of law firms is convinced that that there is much to be gained from a willingness to demonstrate a pragmatic grasp of today’s legal marketplace.

Typically, the rewards for the law firm are financial: should they hit on a unicorn, the monetary returns can be huge, as well as the reputational boost given by being associated with a true disruptor in the legal market.

But while the money and fame are both good, oftentimes, the best rewards are less tangible.

‘It’s true; it’s difficult to show to the business real and tangible KPIs. They are more intangible ones,’ says Francesc Muñoz, chief information officer at Cuatrecasas, one of the many law firms around the world who have entered this space. Cuatrecasas is a Spanish firm that has teamed up with innovation platform Telefónica Open Future to create Cuatrecasas Acelera, an accelerator now on its third call after launching three years ago. Cuatrecasas Acelera supports companies at the pre-series A1 phase with mentorship in marketing, finance and business models, as well as 20 hours of free legal advice from 40 participating Cuatrecasas lawyers.

For Cuatrecasas, working with a multinational blue chip like Telefónica has amplified the reach and impact of its Acelera programme. But Telefónica itself also reports the benefits of collaboration in extending influence in the innovation space.

‘On one hand, our network of partners extends our reach and provides us with shop windows to new industries and ecosystems. This allows us to learn from them and eventually enter new markets, hand in hand with market leaders. On the other hand, our partners help us improve our value proposition to entrepreneurs by putting more resources, investment and business development opportunities on the table,’ explains Agustín Moro, global head of partnerships at Telefónica Open Innovation.

‘But some of the start-ups that we are helping become small clients and we hope that they become, in the future, big clients. So you are putting some seeds into the business sector to see if start-ups grow in the future,’ Muñoz adds.

Edmond Boulle, co-founder, Orbital Witness

‘The team comes from the space industry and, when we set up, we were looking at how we could use satellite imagery to solve problems in real estate transactions and litigation. But the real pain points were around other datasets – so accessing all of the information that is required for searches, making that information easier to digest, easier to report back and then communicate to clients. Our system is learning what features to look for from the data, which trains our system to recognise the types of, for example, restrictive covenants, easements, restrictions on the Land Register, and other data sets outside of Land Registry data, that may be indicative of a particular risk in a given type of property transaction. We were one of the first start-ups chosen for the joint PropTech accelerator programme, Geovation, run by HM Land Registry and Ordnance Survey, which means we have their help to innovate with their data.

We came to MDR LAB with very much a fledgling concept, being the earliest stage company they had taken on in the first cohort. The lab was helpful in a number of ways: in terms of access to great advisers, in understanding the wider real estate industry – not just the legal side. By far and away the most important thing was being able to sit down with over 40 of their real estate lawyers, day-in day-out, and just go through how they work in an almost forensic way. This allowed us to identify which bits don’t add value to their practice and were time consuming and repetitive, which we could then meaningfully make an inroad into, in terms of helping them with speeding up or automating.

A good solution is one which works at both ends, so they made introductions to their clients – in fact we’re piloting with a few of them as well. It will be between the law firm and the client to decide how best to allocate the use of our platform, so maybe the client can do some of the work in-house, and then the law firms can maybe do the deeper dive on the due diligence themselves a little later on, and still get the benefit of using us to work more quickly and more effectively.

Lawyers are still typically very risk averse – even among the firms who are pushing innovation, fundamentally, some individual lawyers are more risk averse. I think there’s a sense in which you can be welcomed in initially, and then it can soon feel that you’re having to battle more traditional attitudes. But then, I don’t even put that on the law firms. They are responding to the risk that their clients are willing to take. So if their clients express a desire to take a little bit more risk, the reward from it will be a faster and lower cost service. Quite often, they want to reduce fees as well, but they still want that quality service.

Very recently, at an insurtech conference, someone made a really nice point that when lawyers talk about innovation, they often use the image of a robot. And when they talk about machines replacing lawyers and a) how concerned they are by that, or b) how ridiculous they think that is, they also use the image of a robot. So even in the industry, they’re not quite sure what to make of this.

We’re starting to make some great headway; we’re working with a number of early adopter law firms who are highly respected in the field, and a leading title insurance company and we are going to continue along that path, at least until the end of the year. There’s a point at which you can’t call the next client an early adopter any more!

We’re working very closely with our first customers because their feedback really helps accelerate product development. And Mishcon de Reya was our first customer. We’re also piloting and testing our products with small teams and GCs at the clients of the law firms that we work with. The issues around that are quite interesting because if you’re working with a big law firm with upwards of 50 lawyers, you have one pricing model, which has to scale appropriately and allow for disbursable cost elements. But then you come to an in-house team with three or five people, so you have to think, “How do I make my pricing model work for them?” It’s a different game. How do you go from being a product that’s serving large departments, to serving a client with a smaller number of lawyers in-house if, for example, you are offering a subscription service?’

Those seeds could include investment, although that is not the point, says Muñoz. At Cuatrecasas Acelera, the firm doesn’t take a stake in the businesses that pass through the programme. But the agreement includes an option that, at the next investment round, Cuatrecasas could invest under the same conditions as the lead investor, up to a percentage.

‘It’s really quite a minor percentage of the start-up. It’s completely an option, but other acceleration programmes take a stake in advance of 2%, 3% or 5%,’ says Muñoz.

Culture change

But there is a broader cultural benefit to be enjoyed much sooner, according to Muñoz. ‘You are putting the most innovative people that you can find in your sector in contact with your lawyers, with your teams. It creates a really beautiful circle and a lot of passion within the people that are interacting with them and giving advice,’ he explains.

The head of another law firm-founded incubator agrees: ‘I’ve seen how the legal sector is quite traditional, but also how the firm’s people – the partners, the associates – have actually become a lot more innovative in their thinking just by spending time working on a day-to-day basis with those start-ups based in their building. And actually, with the companies from last year, the majority have continued to work with the firm and have integrated inside, so the firm is now using these new technologies, making them a whole lot better, and they’ve changed their own mindsets, too.’

However, opening up to innovation often means letting go of a mindset focused on success, ingrained by the often adversarial nature of both litigation and corporate law. The reality of start-up life is the ever-present whiff of failure, and that is something that law firm lawyers, accustomed to being the experts, must adjust to. For many, that’s a case of learning how to ‘fail better’ and move on. Being the expert in one vertical might simply not be enough in today’s marketplace, where openness to innovation might be less of a soft skill and more of a business imperative.

‘As a former lawyer for stock markets, I always keep an eye on the new trends in the legal tech niche. The transformation speed in this traditional vertical is so fast that I could not think of a law firm that aspires to be market leader without working with start-ups and using their technologies. All the leading firms that I am aware of have programmes or initiatives to capture and benefit from innovation,’ says Moro.

Making a mark

In a profession often noted for its resistance to change, there can be kudos for those bold enough to be a first mover. According to Edmond Boulle, co-founder of Orbital Witness, a start-up real estate intelligence platform that employs satellite imagery and property data analysis to flag legal risk in real estate transactions, there is a clear advantage for those who get in on the ground at an early stage in technological development.

‘They have a meaningful say in product development. We are listening to that and we are designing our products around the things that they are telling us are painful. They are seeing iterations of the product and feeding back on that, so if you’re an early adopter, you’re bespoking it a little bit to your style of working. As soon as you’ve got a critical mass of customers, it ceases to scale from the start-up’s perspective to adapt your product to individual needs and preferences, and from the customer’s perspective, it’s more of a fixed offering,’ he says.

But, perhaps the bottom line speaks loudest. A spokesperson at one law firm accelerator claims that a growing willingness to embrace technology has meant that not only is there no better time to be a lawyer – but that the efficiency savings of legal tech could even grow market share.

‘Let’s be fair, some parts of a lawyer’s job are not very fun. You don’t want to stay up reading the same lease a thousand times, you don’t want to chase signatures at midnight or hang out at the printer. You want to do the legal work and so the technology enables that by taking away a lot of the drudgery. The smart lawyers understand that they can pull that off, they can get more work, win more competitive panels, they’ll grow their share of clients and have a more fulfilling legal practice.’

A helping hand from Goliath

For the legal tech start-ups themselves, the benefits are much more tangible. For Orbital Witness, coming into the MDR LAB, run by UK law firm Mishcon de Reya, was an opportunity to adapt a fledgling space tech concept – it was the earliest stage company the lab had taken on in its first cohort – into a viable legal tech one, by gaining an inside view of the workings of a law firm.

‘The genesis of the Orbital Witness platform, frankly, was seeing lawyers’ desks covered in papers – from the local authorities, from specialist search providers, from the Land Registry – and every time they were trying to find a piece of information talking about a property, instead of being able to jump to what they wanted, they were either searching through document management systems on their computer or rooting through the desk strewn with papers. It just struck me as very laborious,’ recalls Boulle.

But on top of the opportunity to forensically analyse the working methods of 40 lawyers in the firm, Orbital Witness was able to learn about the real estate industry beyond the legal side and, crucially, meet some clients.

‘We’re piloting with a few of them now. And we’re actually going a little bit further than that as well: we’re building collaborative tools. We saw that a lot of time goes into emails and phone calls between a lawyer and a client. Now, obviously, that’s part of the personal relationship with the lawyer and client, and that’s not going anywhere. But if you’ve got five emails back and forth trying to describe what part of the land the lawyer is talking about, that’s just inefficiency. So by bringing both the lawyer and the client onto a collaborative workspace on the platform, you can cut out a lot of that needless, repetitive back and forth,’ explains Boulle.

For some firms, engagement with start-ups is the result of a process of introspection.

Other benefits for start-ups that join such innovation spaces might include the opportunity to adapt an existing product to a new legal and regulatory environment, or to get that first customer. Those in the latter position face a slow, and sometimes demoralising sales cycle into big law of 18-24 months.

‘We started as a DMS (document management software) six years ago with a focus on law firms. After some years, we realised that law firms are slow to decide and that they don’t have the big budgets large corporations have for growing their organisations. Therefore, we changed our strategy and began offering our product and service to large corporations,’ explains José Manuel Jiménez, CEO of Webdox, a Chilean start-up and beneficiary of Telefónica’s Wayra Chile programme.

Beneficiaries of law firm accelerators benefit from compressing that cycle by piloting their technology to an audience with an intellectual, if not financial (yet) stake.

If a law firm doesn’t ultimately take the bait, the legal tech model, often comprised of Software as a Service companies charging per user even while their founders sleep (as opposed to billing hours), seems to be increasingly appealing for institutional investors – which bring professional management expectations and software company economics into the legal tech ecosystem.

Don’t fear the new legal ecosystem

The result of all this is a new ecosystem within the legal community. Firms are no longer at odds with legal innovators, and lawyers shouldn’t let a fear of ushering in their replacements stop them from securing benefits of their own out of this new norm.

But is any residual fear within the legal services industry justified? At Cuatrecasas, Muñoz thinks not: ‘We don’t see lawyers disappearing from here; we see keeping probably the same amount of lawyers – doing different things, sure, and in a different way, sure – with more support of technology, probably working much more with engineers in order to set up a full legal service, not only legal advice.’

Boulle agrees that the sector will change, but not necessarily to the detriment of lawyers. ‘Certainly the product that we have now is just about starting to make their lives easier and better, and it works in symbiosis with them – we can’t work without lawyers,’ he says.

‘I think there is room in certain parts of the industry to remove particular tasks from lawyers altogether. I don’t think of ours as a “putting lawyers out of a job” tool, it’s just simply saying there are some things where, if the volume and cost of the work means it’s not feasible to have a professionally qualified individual doing a detailed analysis, it makes more sense to balance the risk and the cost and have a machine to assist in the process.’

The realist of start-up life is the ever-present whiff of failure.

In-house legal departments, driving this market with their continued disaggregation of external support, also stand to benefit from a diversified job market for their own skills, as the legal tech sector expands, offering hybrid legal-entrepreneurial roles.

Of course, this is likely to be some way off. Legal tech companies with true brand recognition remain few and far between, with much of the investment cultivating companies applying state-of-the-art technology to commonplace tasks like contract review – hardly the stuff of dreams. And as companies progress beyond the start-up stage, growth will be a challenge, as multiple small operations compete for the bandwidth of law firms.

If the law firms incubating and accelerating legal tech are to believed, private practice has more to gain than lose from embracing technology. An easier life, greater professional satisfaction, and an enlarged – and happier – circle of clients who remain loyal because they share in the efficiency dividend all beckon for those with open minds.

But for those who think that is too good to be true, perhaps becoming a stakeholder in the digital future is at least a way to avoid ending up at its sharp end – sharing the gains of technology rather than counting among its casualties.

The use of technology by in-house teams is evolving – particularly compared to what existed a few years ago, two years ago, or even one year ago. Yet still, for legal departments, change is much less quick than in law firms.

Big legal departments are investigating the possibilities and opportunities offered by new technology. There was a survey done in 2017 targeting French in-house counsel, which showed that many needed more software and applications for legal tasks. But at the same time it was more commonly expressed – by more than 50% – that this was not a need at present.

I wouldn’t say there is a kind of collective trend: I think it really depends on the culture of every individual, every lawyer, the culture of the legal department, and the culture of the company itself. But if I look at a period of five years, there is an increasing trend towards a willingness to understand what is happening, what works and what does not work in terms of technology, what the best practices to benchmark for in-house lawyers are – and also to think in terms of investment and return on investment.

I remember speaking to the GC of a very big French company. He said, ‘You know, I’m convinced that some of this technology is going to be very useful for the legal department – but there is a cost, and I need to convince the executive committee, or even the board, that the cost is justified: that we expect a return on investment, so it means cost reduction for the legal department, how we are going to be able to increase the performance of the legal department in terms of service delivery, satisfaction of the clients and also improvement of our own KPIs.’

(Virtual) reality check

Areas in which some in-house teams in France are using technology include legal research and information, case matter management, contracts management and contracts automation, legal knowledge management, and project management. And, of course, e-billing, selection of legal service providers, benchmarking, sharing of the best practices within the legal team – and this is especially the case in big legal departments. Some of them are using predictive justice tools – although it’s very few, it’s just the beginning – and I would say it’s more used by law firms than legal departments.

As far as machine learning and real artificial intelligence go, I think we are still a little bit far away from that. For blockchain, especially for smart contracts, there is a start: for instance, for intellectual property rights management. Some are thinking about the possibility of using blockchain technology to manage the participation of shareholders during general assembly. There is also the smart contract approach of using blockchain technology for contracts between shareholders, for instance to organise the control of the company, or to have agreement provision in the case of share selling. As far as I know, legal departments do not directly use big data analytics, but they can work with some law firms that do.

I think that the particular areas right now where the technology is the most useful are document review, case review administration and case analytics, legal research, document drafting, knowledge sharing and communication. But when you think in terms of legal writing and advising clients, I think that – right now – the effect or impact of the new technology and data analytics and so on is very low.

Some are thinking about the possibility of using blockchain technology to manage the participation of shareholders during general assembly.

When you look at the current legal technology and new legal technology and what they propose in terms of services, it’s moving really fast. But the next steps – more deep learning, machine learning and real artificial intelligence – frankly speaking, will not come within ten years. The creator of DeepMind, which was acquired by Google, said something which was really interesting: when you hear people saying that tomorrow everyone will be replaced by robots, and we will be able to have a full, sophisticated conversation with an artificial agent, he said no: that’s not serious. What is serious is the ability to replace standard analysis and decisions with robots. Analysis further than that, when there is more room for subjectivity and when the exchange between different persons is key in the situation, the Turin stage of artificial intelligence, machine learning, deep learning, deep thinking and so on is not at the right level. We are not there yet.

Redefining value add

One important point when considering the value of technology – something which is happening in some law firms already – is change in the value chain of the legal department.

Typically, you have information entered into the ‘system’ of the in-house team and, at the end, you need to provide a service – advice or a solution. All the segments of the chain, like information gathering, information analysis and treatment, document drafting, due diligence, are going to be more and more digitalised, and done increasingly less by human beings. This means that the skills required for lawyers are going to change, and the quality of the relationship between the client and the legal adviser is going to become more important. Right now, I don’t see any robots directly advising clients because they are not sufficiently sophisticated. But for the lawyer to give good advice, fully understanding the needs of the client and having sufficient time to discuss their analysis with the client – what are the facts, what is the law, what is the content of the regulation, what is the state of the jurisprudence or case law – all of this is going to be done faster, which will leave more time to deliver very high quality advice and service.

The freed-up time can then be used on other important areas. Lobbying is one of them because, surprisingly, in France, the lobbying role of lawyers is not always taken into account by legal departments. Giving the possibility to legal teams to think more about the future of the law in their domain regarding their businesses or the businesses of the company is very important, but you need time to do that. It’s not directly productive, but it can have a huge impact over time. It will also allow departments to take time to train non-lawyers and to increase the global level of the legal education in the company – to reduce the common questions. The other side of that is that there’s also the potential to increasingly automate processes – improving efficiency and quality of services across the board.

Training lawyers of the future

What we need to be doing in the here and now is, when we train future junior lawyers, they need to know how to use data analytics, how to use the new tools which are available on the market, and maybe we also need to train them to understand how algorithms work, even if we are not going to create hordes of lawyers who can code. To understand what it means when you code, and what are the consequences in terms of legal mechanisms, legal analysis, or legal documents, to have fundamental tools to understand what coding means, is going to be very important for them.

The second important point, I think, is to reinforce their soft skills, because the relationship with the core business will be more and more about the quality of the relationship. For instance, what about empathy? Being able to take time to listen to the client, to take their point into account. Knowing that the time you spend for legal research, information retrieving and analysis is going to be reduced and reduced and reduced, if you want to maintain the same revenue for a law firm or the same level of service for a legal department, you need to perform better elsewhere.

As educators, we need to be doing these things. If we do not, we hear from young students who are going to intern for six months or a year, coming back from legal departments or law firms saying, ‘Well you know, we had to work with this tool or that tool, or there was discussion about using a new tool to improve the relationship with the external suppliers, e-billing, and so on, and we didn’t have any clue about what they were talking about.’ Even if you are not convinced, you need to better train your students on these kinds of tasks because they ask for it. There is a demand for it.

Practitioners know better than academics what are the most up-to-date tools they are using in the industry. But I think it’s the role of academics to prepare students to be able to be flexible, reactive and to be able to switch from one tool to another one and to have a global vision, a global understanding of what is happening. And to make them aware that there is a certain level of uncertainty in practice. Usually, when you study law, you do not like that: you like certainty, and the more it is fuzzy or blurry, the less you feel comfortable. We need to prepare them for that.

Technological Darwinism

Now, the question is: is technology going to kill some jobs? I would say, yes of course. Will it promote the creation of new jobs? I think so. Will it change the type of skills required for lawyers? I think it will. I think that the development of these new tools is more an opportunity than a threat if they provoke a change in the business models and the way lawyers deliver their services in the interests of the client. But if some so-called artificial intelligence can lead to weak services and fragile legal advice, then they will be stopped or simply not used. So I think the market will decide and will make a distinction between good stuff and bad stuff.

It seems strange, because sometimes lawyers are perceived as being very conservative, but I can tell you that in France, the legal domain is just after finance in terms of being active in start-ups. I mean, legal tech versus fintech versus other kinds of activity – legal tech is very, very active. Recently, I was surprised to find that that the legal tech that we observed two or three years ago is still alive. Maybe, at the end of the day, you have a Darwinian system where the most adapted survive. You cannot have, for instance, tonnes of companies in France proposing predictive justice because the market is not so big. But I would say that the legal domain is very well placed in France, and could rank well in terms of intensity and innovation; it’s very active. Which is surprising, because lawyers are perceived as being the most conservative compared to some other professionals.

An important objective or challenge is to make in-house counsel more comfortable with the technology, doing demos, sharing success stories, sharing best practices and, to a certain extent, kill the myth that technology is too complicated: that it’s not for you guys because you are lawyers.

I would say that at Bombardier Transportation Group, we’re not using technology in the way we could be and should be using it – I would self-critically say that we’re in the bottom third if I look around – but we have taken the decision, as the leadership team in the legal community, to tackle it.

Global application

I see two challenges of employing technology in an in-house legal context. One is budget and the second is that we need software applications that work around the globe. It doesn’t help us if we find the perfect solution for the legal team in Germany – we need to find the global application that the legal team can use in the UK, in France, in Sweden, in Thailand, in the US, in Australia, in South Africa, in India – you name it. It needs to be a software that is so generic that it can be universally used, possibly also in different language settings, because despite being a global firm where English is the company’s language, we still do have local languages used in contracts.

Be brave: think long term

Budget, of course, is always an issue because you need to have a convincing business case. You need to go to the CFO and say, ‘I need the budget of X, I will invest in legal tech applications, and the return on the investment is Z, and Z is higher than X.’ But how do you make that case? I would not like a conversation, which I’m concerned some of my colleagues have had, where the CFO says, ‘Sure, I will give you the budget of X, but then please sign here that you will, in return, reduce the head count in your legal team by 20 or 30%.’ It doesn’t work like that.

I think the return on the investment in legal tech and software application is mid term and long term, it’s not short term. It’s not: you buy this software or this contract generator, or this chat bot and then Peter and Paul can take a hike. It’s not that simple, and if that’s the equation, then the equation will fail and in-house legal teams will not be successful in convincing their CFOs, because they will be shooting themselves in the foot. In the long run, they may have a lower need to hire new in-house lawyers. Even in the mid term I would say that’s doable, but not in the short term. You need to be brave to make the investment, because it’s difficult to predict the yield of return from the investment for the legal team.

Window-shopping for tools… and best practice

I see the benefits of legal tech software and legal tech applications not as a means to cut down on headcounts in in-house legal teams, but as a means for in-house lawyers to be relieved of wasting their time on administrative, repetitive, non-value-add work, so they have more time to spend on brain work where, luckily, software is not yet better than the human brain or the legal mind. I really see it as an enabler to focus more on value-added legal work to support bringing the business forward, so I think we are doing our own in-house lawyer profession good if we find ways to manage our time and our energy better. I’m coming from the perspective of increasing the efficiency, effectiveness and impact of in-house lawyers, rather than just looking for a cost-cutting measure.

Recently, a German law firm showed me a smart contract generator tool. The software asks you questions, asks you to provide information and data and then after 50 questions, you have a fully fledged procurement contract. It’s such an easy approach because a company that develops tech software for lay people came up with this idea and they just transferred this approach, a way of guiding a lay person through legally relevant stuff to create the output, which then is a contract. I see various applications for that, for simple contracts that are really standardised, like non-disclosure agreements, a simple lease agreement, a simple purchase agreement, or a simple labour contract. It can be used for any contract that a company uses on a repetitive basis. So it could be for one company’s licensing agreement, it could be for another company purchasing raw materials, it could be for another company purchasing professional services. Whatever the contract, on a repetitive basis, from Monday through Friday, it can be easily standardised and then created by clicking the mouse, rather than typing letters and numbers for hours, creating and drafting a contract.

85% of the jobs that people will have in 2030 don’t exist today – which is quite frightening.

Another area is copying what service providers have created for end users. For example, one telecommunications company in Germany created an application that you can use if you’re suffering from problems in your WiFi at home. Rather than calling a service line and waiting for 30 minutes hearing lousy music, the app connects to your WiFi router and does some things in the background and tests the connection without you seeing it. If the app (that you can use on your smartphone) detects a problem, it guides you through solving the problem. You don’t have to waste your time on a service line, you’re not wasting money on that call, and you get a quick solution. Something like that could also be used for standard legal questions in a big company that the business asks again and again and again. You just feed the software with information that only a lawyer can give, the software works by itself, the business is supported and they don’t have to phone up the lawyer.

The magic pill that I would like to find, and then eat and swallow, is a software application that we feed with the terms and conditions of our contracts. Based on our project execution experience, the software tells me which are the hot clauses and the cold clauses and, on the hot clauses, what different clauses we have used and how we can improve those hot clauses by learning from our own contracts around the globe. I think we can greatly improve knowledge management when it comes to our own contract execution around the globe.

2030 vision

I was reading the other day that, according to one global consulting firm, 85% of the jobs that people will have in 2030 don’t exist today – which is quite frightening, because it means that only 15% of today’s jobs will survive to 2030. But I would not say that 85% of what I’m doing with my legal team will no longer be done by us in 2030; I see different angles.

There’s one angle where I have the private citizen in mind, and yes I think there will be a huge disruption of how people like you and I, in our private lives, use legal services. I think if you look at the available tools already now, there will be less and less need to engage a lawyer to help you resolve your legal questions and legal disputes.

For companies, by 2030, if they are smart, they will have smaller legal teams but still continue to insource legal services, so they will use less and less external legal advice. I would say that smart in-house legal teams will have managed to develop in-house legal expertise and knowledge in areas where they are no longer dependent on external lawyers, and they can only do that because they are no longer wasting their time and energy on low-skilled, legal administration work. I think it will help the smart in-house legal teams to improve legal quality in areas where they are currently dependent on external experts, so I think it will be tight for external lawyers rather than for in-house lawyers, because there will simply be a decrease in engaging external lawyers.

But not for the real global law firms who make a fortune from global transactions where you need so much more brains and hands than a mid-size law firm can possibly get together. For mid-size law firms, it will be tough moving forward into the future, and you see it already – there’s a big trend of consolidation in mid-sized law firms. I would say that the landscape of law firms will look very different in 2030.

It was acceptable in the 80s

We are quite a conservative profession, at least in Germany, and we are under immense pressure to stop conserving the way we work rather than opening ourselves up to new ways of working. The days where a partner or an associate in a law firm can shift all technical stuff – word processing, Excel, PowerPoint – to an administrator are over with and, sooner or later, there will not be a person who does all that for you and you charge it to your client. I think we all need to step up our technical skills and internet skills and software skills, because our way of working as lawyers, and in-house lawyers, is pretty much the same as in the 1980s –and I don’t think that that’s sustainable.

The proliferation of blockchain technology has forced nearly every sector to re-examine traditional ways of doing business. Nowhere is the potential more apparent, or the sector more traditional, than in the negotiation, creation and execution of contracts. If the blockchain evangelists are to be believed, the manner in which parties’ contract will be changing drastically in the not-too-distant future. But while a number of high-profile success stories illustrate the transformation potential of the technology, it’s clear that there is still a way to go.

Blockchain understood

To understand blockchain technology and the potential value that it brings to business, think of how an ordinary business transaction works: there is an agreement and exchange of goods or services between parties. Each party keeps their own ledger, which records the transaction. But because the ledgers are held independently, there is scope for discrepancy between them – be it through error, disagreement or fraud. Traditionally, this was mitigated by introducing a third party to the transaction – usually a bank. But reliance on a third party introduces cost and inefficiencies that need not be there if there was a way to create and maintain a singular, shared ledger – one that is equal parts transparent and secure.

Enter blockchain

A blockchain is a series of mathematical structures, inside which individual transactions are recorded. The record of each transaction – each ‘block’ – is mathematically contingent on the block that came before it. The transaction becomes a permanent part of the history of the blockchain and, in that way, it cannot be tampered with: once it is added to the blockchain, all subsequent transactions are recorded in relation to that block and all of the blocks that came before it. Following each transaction, the updated blockchain is distributed to each participant. In this way, blockchain becomes a decentralised ledger that is impossible to tamper with effectively: any attempt to change a record in the blockchain will put it at odds with the version held by every other participant in the blockchain, as well as all of the subsequent transactions that have been recorded.

Put simply, blockchain technology allows for a distributed, decentralised and secure ledger that eliminates the need for third parties, while providing a level of validity to participants that would otherwise have been impossible. It is this technology that has made cryptocurrency like Bitcoin a viable endeavour. But the applications of blockchain are far more varied.

Smart contracts

Smart contracts are one such innovation made possible by blockchain technology – though as a concept, smart contracts have existed since the early 90s. The idea is that instead of a paper contract – one that amounts to the words on a page and the interpretation that third parties give them – one could record a contract in the form of computer code. The code not only provides for the terms of the agreement, but the execution of it as well. When the obligations of one party are satisfied, the platform behind the contract will automatically release the benefit owed by the other party.

The key to smart contracts is decentralisation – there are no banks or other third parties involved in the execution of the agreement. The idea is to allow the creation and execution of a contract between two people to be as simple and direct as possible.

The obvious question follows: where is the smart contract actually stored and how can it be possibly be trusted?

Blockchain technology is the solution. The decentralised, theoretically uncompromisable central ledger makes for a perfect arbiter for the integrity of these agreements. Once coded, the smart contract is added to the blockchain ledger, with its integrity provided for in the same way as anything else on the blockchain. If the transaction calls for it, the money at stake can be paid by each party into the smart contract using cryptocurrency, at which point the contract will hold the money in escrow until the necessary conditions are satisfied.

In theory, removing the element of trust between parties to a contract should make for more reliability.

‘What we have realised is that smart contracts are rapidly becoming an alternative way to transact, with more than $10bn raised through smart contracts in the last 18 months,’ says Olga V. Mack, vice president of strategy at Quantstamp, a company working to build security infrastructure for blockchain-based smart contracts.

‘What we have also noticed is the rapid proliferation of this technology. The widely cited figure is that, globally, there were more than 500,000 smart contracts that existed one year ago. That number has grown to about five million that exist today. The use of smart contracts has been growing exponentially and is showing no sign of slowing down.’

Smart and secure