Despite clear interest from the in-house community, the growth of legal tech hasn’t achieved the same blistering pace that fintech has managed. The rate at which the financial sector has caught on has meant wide-ranging technological innovation, at every level of the industry.

‘As successful fintechs have rapidly matured from start-ups to mature technology disruptors, banks have started the journey to transform their core digital capabilities, with several areas of focus. These include: a digital-native customer experience; big data and advanced analytics; moving towards a scalable technology landscape through cloud and automation; adoption of APIs (Application Programmable Interface),’ says Giulio Romanelli, associate partner at McKinsey & Company.

Part of the reason for the legal profession’s shortfall is a lack of enthusiasm on the part of the legal community and a natural aversion to change, but that doesn’t tell the whole story.

‘There’s a lot of hype in the space and I think there are often very clever technical solutions looking for problems,’ says Chris Wray, chief legal officer of Mattereum, a start-up working to bring blockchain technology to business.

‘Although there is interest in the theory or the potential, I think there’s also, quite rightly, a demand for: what’s the use case right now? I’m not sure I would criticise the profession generally for being somewhat cautious. I do think there’s a curiosity and a willingness to try and learn about both the potential implications and to update skills accordingly but there’s also, I think, the correct recognition that a lot of the use cases are still in the future.’

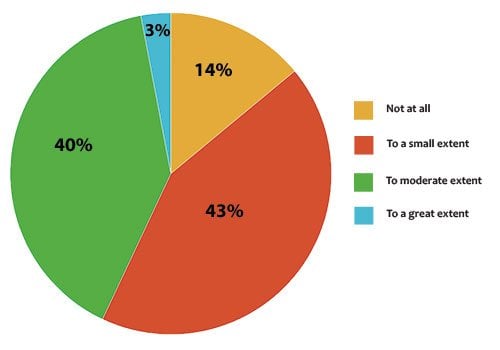

The reality is that, for blockchain, alongside more prosaic types of technological assistance, many legal teams remain in monitoring mode – surveying the field and keeping tabs on likely applications, but not necessarily investing just yet.

‘We simply have to be clever in finding the right applications, and also doing a little bit of trial and error rather than just rushing to one of the service providers, buying their generic application and then learning later that it was not the most suitable application,’ says Dr Alexander Steinbrecher, head of group corporate, mergers and acquisitions and legal affairs, Bombardier Transportation.

‘I’d rather invest a little bit more time window shopping and defining our needs rather than rushing ahead and being the first users.’

The sense among the in-house counsel surveyed was that their private practice counterparts aren’t faring much better: just 40% of respondents said their external legal advisers were implementing new technology to deliver their legal services and solutions. Still, one common sentiment among those interviewed was that private practice has a role to play in being a first mover in the legal tech takeover, setting the example for in-house teams to follow.

‘When we first undertook the research process of finding out what was in the market, it came as a pleasant surprise to see that law firms are leading innovation in the legal sector and how many are doing things like working with start-ups in developing new technology,’ says Cristina Álvarez Fernández, head of legal Europe at transport infrastructure developer Cintra.

‘Clients in particular are trying to change the way that they invoice, looking at alternate fee arrangements or, in some cases, bringing more work in-house. As a result, I think they have been forced to find ways to reduce cost and maintain their profitability. But at the same time, they will have no doubt seen other industries disrupted by technology and seen that this is the way forward.’

In an increasingly competitive European marketplace for legal services, corporate pressure on the billable hour is driving law firms (including those at the sharper, mid-sized end) to increase their own efficiencies, and reshape their service offering and value add for companies.

‘Let’s be fair: some parts of a lawyer’s job are not very fun. You want to be doing the legal work and so the technology enables that by taking away a lot of the drudgery. The smart lawyers understand that they can pull that off, they can get more work, win more competitive panels, they’ll grow their share of clients and have a more fulfilling legal practice,’ says a spokesperson at one law firm-sponsored legal tech accelerator.

Bridging the Gap between Technology and Four Generations

When acting for in-house counsel, adaptability is a quality that independent law firms have in their favour. It is the agility of their operations and the ongoing awareness of novel developments that can give them the competitive edge.

Globally, experts predict that by 2020, millennials and generation Z will account for more than half of the world’s working population. For the first time in history, four generations with an age gap of over 50 years will be working side-by-side in the same environment. Millennials are rapidly becoming the most powerful connector between these generations and will soon be in leadership roles within firms and in-house counsel positions. They are the first generation to grow up in a fully digital society, which accounts for a completely different approach to objectives. Leveraging the most technically savvy talent, coupled with a firm’s visionary decision-makers, will inevitably create a lucrative approach to meeting and exceeding client expectations.

As found by a survey for millennial lawyers and their millennial clients conducted by World Services Group, firms should look to develop expansive multigenerational strategies for their new client groups, offering the most comprehensive array of professional services. They should look internally to create committees that focus on the millennial client, on process efficiencies, and on keeping current with the latest technological developments. Then, by focusing on the client’s business as a whole, savvy firms may quickly become trusted partners asked to act on their strategic advice for deals or territories that they had not previously supported.

The biggest evolution to the legal industry is yet to come, and while technology is the cause, it is also the very thing that is bridging the generational gap in the industry. The successful law firms will be easily identifiable, not because of the technology they utilise, but because as a firm, the indispensable need for flow among the generations will create a new culture that more easily matches client needs.

But some in-house are more sceptical about the extent to which law firms are truly aboard the innovation wagon.

‘It’s mainly driven out of fear. It’s less: “Let’s be super innovative and change the market and then ultimately be super profitable”, it’s more: “I think something’s happening and it may have a negative impact on our business model so let’s work on it to manage the negative impact”,’ says Matthias Meckert, head of legal at PGIM.

‘The activity on the side of the law firms – all of them talk the talk but only a few are actually able to deliver. It may have something to do with the fact that law firms are run by lawyers and rarely by entrepreneurs. Behind the scenes, many admit that they are fearing the investment. The ones who invest do really exciting stuff.’

While in-house teams might be more cautious when it comes to making decisions on which solutions to adopt, at law firms, the conversation is sometimes clouded by existential angst.

‘The conversations we are having with in-house teams on the application of AI technology are different to the conversations we are having with law firms. With law firms, there’s always that concern of: “If we adopt this technology, how is it going to affect our model? How is it going to change the way that clients perceive us? Is it going to make the client value us less because we’re using technology to support us in the work?” Whereas with in-house teams, it’s fairly straightforward: “I need to make a change, and I can see that this is going to make my life more efficient, more interesting and more stimulating” – it’s a much less complicated discussion,’ says Emily Foges, CEO of legal AI platform, Luminance.

Disruption – at the margins

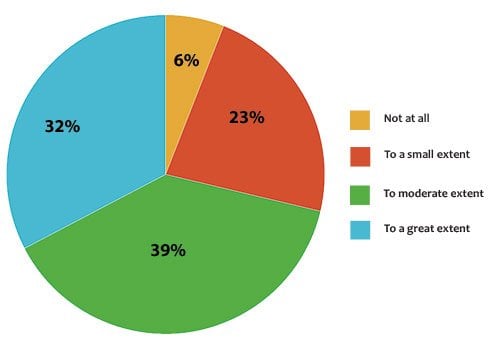

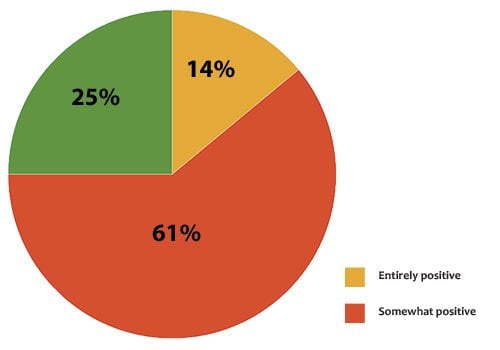

When asked whether technology had the potential to disrupt the legal profession over the next five years, 84% said they believed that technology will be disruptive. The real trouble comes when trying to drill down on what form this disruption might take.

Just 6% of those who believed technology will be disruptive in the next five years thought that the disruption would be negative. 66% felt that it would be somewhat positive, and 29% thought that the disruption would be entirely positive.

Between the believers and non-believers, there is room for nuance. Many GCs are taking an approach that falls dead in the middle of those who think that tech is going to revolutionise the profession in moments and those who think it’s all smoke and mirrors with no real capacity for change. Instead, they believe that rather than technology being a disruptor of the in-house legal role, it does not go far enough to modernise and truly transform.

‘By implementing some tech tools you get a 10%, maybe 20% efficiency increase. This is not really disruptive, this is where I am improving a little bit, I’m streamlining existing structures, but not changing the fundamentals,’ says Meckert.

‘Change gets really exciting once you say, “Let’s start big picture and not with the details – why are we doing that, how do we create value for our business, should we outsource or should we collaborate with others?” Then you start really changing the game.’

Most in-house commentators are confident that the core tasks carried out by lawyers are unlikely to face the kind of disruption that renders the profession obsolete. Although standard and routine work is likely to eventually be automated, businesses will still require lawyers to provide advice on more complex issues such as risk management and corporate governance. Many anticipate an opportunity to engage in more strategic, value-added work, such as relationship-building, lobbying and training across the business. Jobs lost are predicted to be on the routine end – perhaps paralegals, those providing exclusively contractual or notary services, or those providing non-complex high street advice.

private practice has a role to play in being a first mover in the legal tech takeover.

‘According to one global consulting firm, 85% of the jobs that people will have in 2030 don’t exist today – which is quite frightening, because it means that only 15% of today’s jobs will survive to 2030. But I would not say that 85% of what I’m doing with my legal team will no longer be done by us in 2030,’ says Steinbrecher.

‘… Smart in-house legal teams will have managed to develop in-house legal expertise and knowledge in areas where they are no longer dependent on external lawyers, and they can only do that because they are no longer wasting their time and energy on low-skilled, legal administration work.’

Far from reducing headcount in-house, it will actually help combat attrition, some predict.

‘People are less interested in doing day-to-day work on a repetitive basis. People would like to do projects which are more challenging, would like to be empowered. So if you could outsource more administrative and bureaucratic things to a service provider or a tech solution, super, as those tasks need to be completed,’ says Meckert.

‘We embrace those solutions as resources would become free to do higher value, higher risk, more intellectually challenging, more fulfilling work. This keeps my team engaged and allows a better contribution towards the business.’

Similarly, on the law firm side, a digital revolution must be accompanied by an analogue one for any real disruption to occur.

‘Law firms need cultural disruption. Lots of law firms talk about being disruptive, but very few are. There has been very little disruption of law as a service and the change that will be best received by their clients is unlikely to be technology led,’ says Ruth Pearson, general counsel of LendInvest.

A (value) chain reaction

The ecosystem of law firms, their clients, businesses, their in-house teams, and third-party legal tech providers has always been delicate, but the surge of innovation and technology is challenging the value chain to shift to accommodate the changing roles played by each link.

In light of this, each player must go through a process of understanding the space they occupy in this new value chain. Suddenly liberated by the digitalisation of research, due diligence, analysis and document drafting, lawyers will be free to build on the customer relationship by being more responsive and alive to the impact of their advice – particularly in companies moving at a highly innovative pace.

‘If my business is now fully embracing, for example, processing and collecting data and I could patch my piece of the puzzle – the legal data – into that platform, that’s great. In the age of platform industries, the law department can’t be an island, it needs to be integrated and fully aligned with the business and its digital strategy.’ says Meckert.

‘The best inspirations are those I get from conversations outside my “home” industry or with non-lawyers. Those ideas challenge the way we think traditionally.’

Patching into the corporate zeitgeist enabled the Cintra legal team to leverage company-wide investment in technology for the legal team and plan its own technological upgrade. The legal team has worked closely with the IT team to investigate potential new legal tech tools.

‘This isn’t something that’s unique to legal, it’s been happening in other departments already. In general, our company and the group are very interested in innovation and new technology,’ explains Álvarez Fernández.

‘I think that in time, we will see the relationship between in-house departments and external firms change as a result of technology – mostly where fees are concerned. I suspect that the fees of law firms can be reduced, or at least controlled, depending on the market and matters at hand. But I don’t think the interplay will shift.’

Many agree that they do not see an Uber-type revolution arriving on the horizon for the external legal services market, although most concede that there will be some future adjustment of legal service providers.

‘It will be a game changer in the end. Alternative service providers are entering the market in Europe (some have been in the States for a long time now) and some of them have their own technology,’ says Sánchez Soriano.

‘I’m also seeing small law firms with very, very specialised people in technology projects. I think that is becoming interesting because these are not the typical law firms that we are used to working with, but maybe for very technological projects, you’d call these people who are doing things in blockchain or using other technologies.’

Human resources

One other very significant way in which this trend towards technology is changing legal departments and private practice firms is in the makeup of their personnel. 60% of those surveyed for this report felt that today’s lawyers were not adequately equipped to adapt to technological changes within the legal profession.

In response, a focus on technology innovation has led, in some cases, to the creation of roles to specifically facilitate transformation, as innovation managers, data scientists and legal technology administrators begin to enter the field, particularly in law firms. However, such functions are currently less common in-house.

‘Sometimes I have found people in-house who, additionally to their own duties, are in charge of innovation, but the problem in many cases is that these people don’t have a real budget for implementation or even worse, that they don’t have the support from the general counsel or the wider business,’ says Sánchez Soriano.

But, at least on the technical side, some predict that these roles could eventually permeate the in-house ecosystem, as legal specialists with the responsibility for licensing and maintaining tools and platforms like the standardised written and coded terms utilised in smart contracts. Digital legal officers or lawyers that compile software tools with intelligent applications could evolve.

‘The new role of lawyer is more likely a legal process designer to some extent,’ says Dr Volker Daum, general counsel of B. Braun Group.

‘… This will create and maintain jobs, and may even create future jobs, because it’s not just legal advising anymore – we are part of the process and the value chain.’

But equally, although the nature and nascence of new technology makes it difficult to immediately separate the truly transformative from the passing curiosity, hard tech skills of some sort will inevitably be in need of an upgrade.

‘We have projects focused on everything from blockchain to machine learning, so as lawyers, we need to understand these technologies but also provide legal advice for the new questions and challenges that will arise as a business,’ says Sánchez Soriano.

‘We put a high premium on lawyers who understand our business well.’

‘…We will be considering all this for the training we need to give to our lawyers and the people we will be hiring in the future, so that we are able to provide legal advice to innovative projects. If you don’t understand blockchain, for instance, it will be very difficult for you to provide advice on it.’

Counsel are divided over the extent to which it will be necessary for lawyers to learn coding, beyond the skills that will likely be taught as a routine part of elementary education for future (and, to some extent, current) generations.

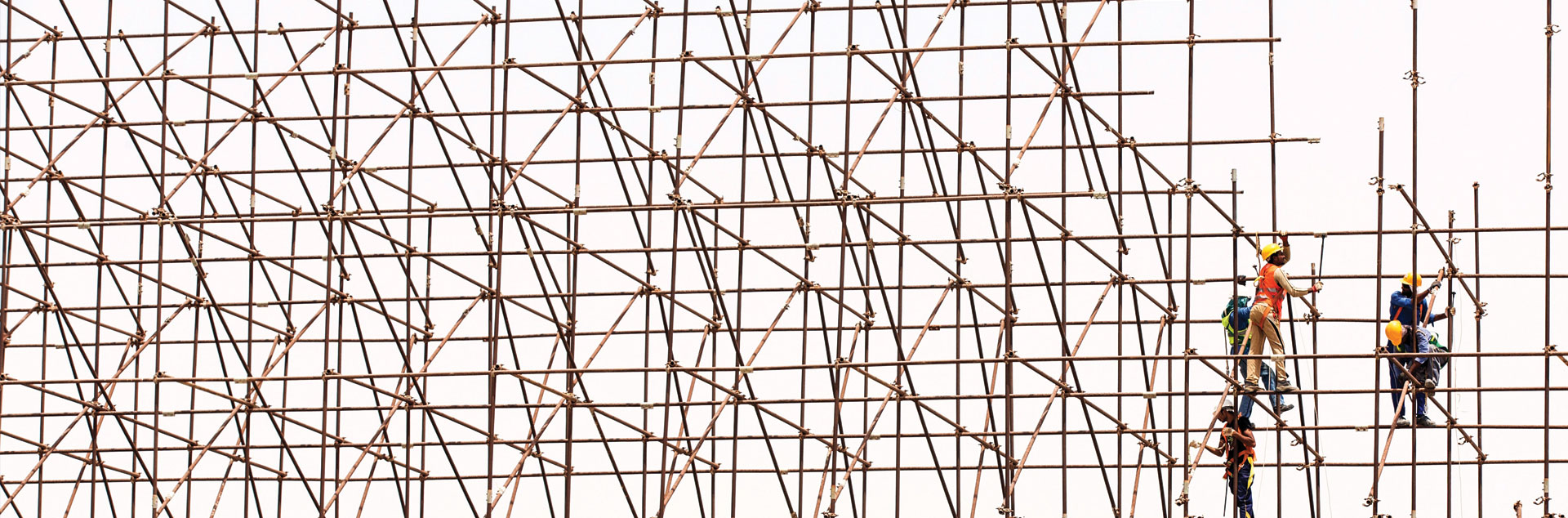

Shaking the foundations?

If lawyers entering the profession today are required to be of a different breed than those that came before them, the question must be asked: are legal education institutions preparing them for this?

Up until now, the bedrock of a solid legal training has been the time spent as a trainee or junior lawyer on due diligence, contract drafting and analysis.

‘We can already remember (fondly or not) the time when, not so long ago, junior lawyers would spend hours preparing first drafts of transactional documents and hence were indirectly trained to the underlying issues behind a specific drafting or wording,’ says Olivier Kodjo, general counsel of ENGIE Solar.

But even if the potential impacts of automation and AI are overblown, these institutions will have to adjust to avoid an undermining of the experiential foundations of the profession. Alternative training models will likely have to be found: a training that neglects the technological skills that are becoming part and parcel of the job is becoming increasingly unfeasible.

‘As educators, we need to be doing these things… Even if you are not convinced, you need to better train your students on these kinds of tasks because they ask for it,’ says Professor Christophe Roquilly, Dean for Faculty and Research at EDHEC Business School.

However it is achieved, demystifying technology for lawyers at all levels – and thereby equipping them for an innovative, digital future – will likely be a bridge to the elusive culture change that underpins the successful evolution and future-proofing of the industry.

‘Innovation flows much better when people are able to see machine learning not as magic, not as something that someone with a magic wand goes ‘Ping!’ and it starts working,’ says Professor Enrique Dans, Professor of Information Technologies and Systems at IE Business School.

In today’s business world, more than ever before, learning is a lifelong pursuit and it is the responsibility for those at the top of each organisation – the corporation, the law firm, the law school – to have the foresight to set a tone that prioritises innovation and agility. For true innovation to take hold, there needs to be an agreement of what constitutes good service and an alignment of priorities and mindsets throughout the organisation and the value chain – to avoid each party being left incompatible with the other.